Opinion In Manipur, beyond optics

Developmental projects can be a catalyst for a return to peace in the state if they are accompanied by initiatives that address faultlines.

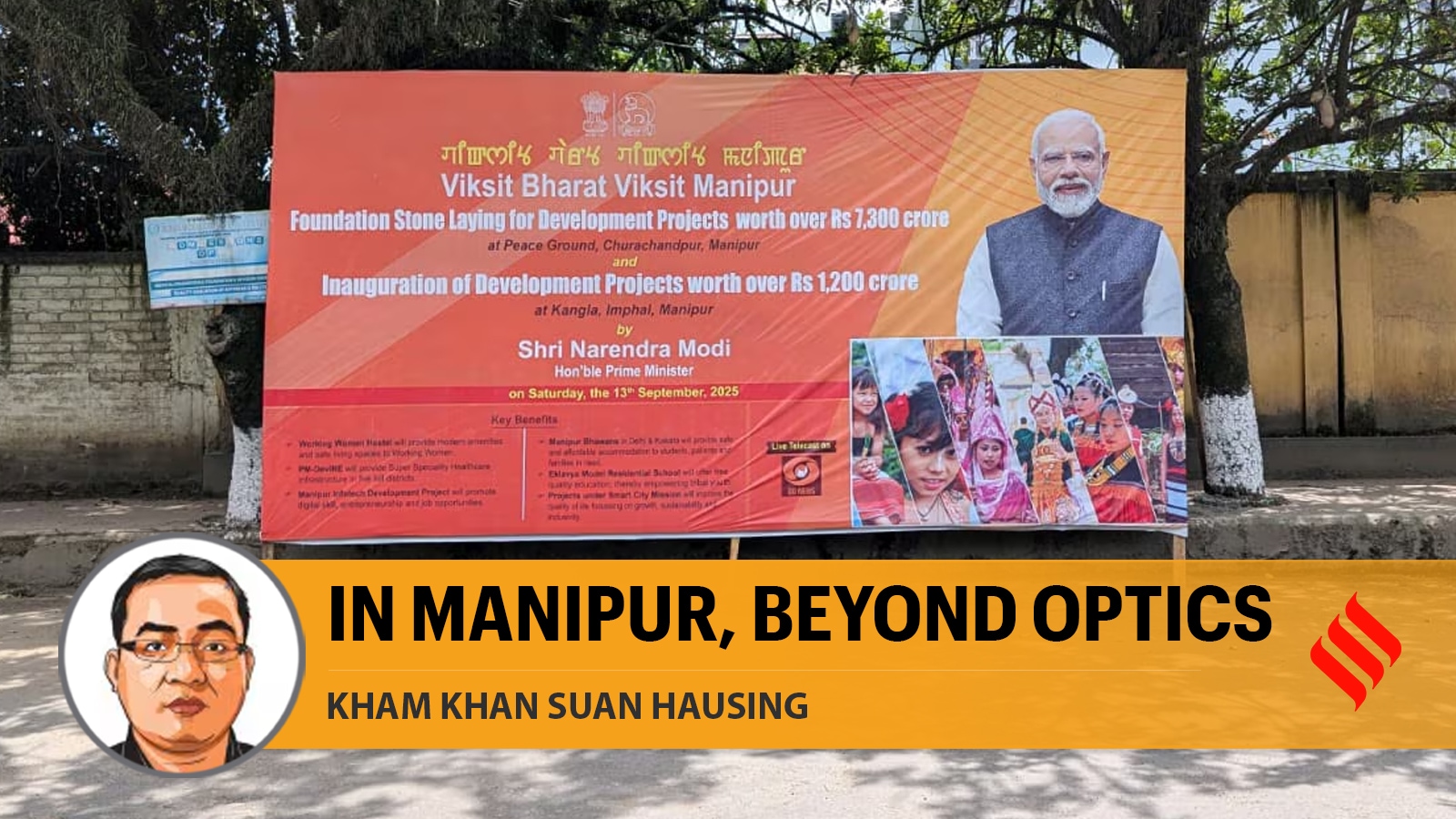

Posters welcoming the PM were erected overnight in Imphal. (Express Photo)

Posters welcoming the PM were erected overnight in Imphal. (Express Photo) After turning his back on the state for more than 123 weeks, Prime Minister Narendra Modi finally visited Manipur on September 13. That he chose to visit the Peace Ground at Churachandpur and Kangla Fort in Imphal to address two communities separated and bruised by over two years of violence is symbolic and sends the right political optics. Befitting one of the most anticipated visits in recent memory, Modi unveiled 19 development projects worth over Rs 7,300 crore for the state in Churachandpur. These development projects, PM Modi claimed, would be instrumental in easing life, strengthening the infrastructure, digital access, education, and healthcare in the state.

The fact that the Prime Minister weathered the heavy downpour to visit Churachandpur by road demonstrated his political resolve. However, his overemphasis on development and the conspicuous failure to lay down a political roadmap for resolving the over two years of violence in Manipur is being seen as a wasted opportunity across the divide. In that sense, there seems to be a certain absentmindedness about the trauma of families who have lost their loved ones and an underplaying of the suffering of the thousands of internally displaced persons who continue to languish in various relief centres across the state in subhuman conditions. Loud declarations of projects may be useful as a carefully choreographed event for political optics, yet the silence on substantive concerns with respect to peace, justice, and the reluctance to frame a commitment to a rules-based constitutional order where citizens are accorded equal protection of the law may not be particularly helpful in winning the hearts and minds of the people.

To be fair to PM Modi, development has always been seen as a big equaliser and a panacea to solving endemic social, economic, and political problems. Since the founding moments of India’s republic, the magic bullet of development, centred around big infrastructure projects, has been prioritised as an instrument of state-building because of the trickle-down capabilities of such initiatives – the promise to remove poverty and reduce inequality in the society. Yet, beyond the material promise of peace, progress and prosperity — a point underscored by PM Modi in his speech in both the places — development is seen as a discursive construct. Wolfgang Sachs, one of the leading economists of our times, aptly captures this point when he contends that “development is much more than just a socio-economic endeavour: it is a perception which models reality, a myth which comforts societies, and a fantasy which unleashes passions.”

What is unmistakable about PM Modi’s speech in Churachandpur and Imphal is the repackaging of development projects that have been in the works for quite some time as vertical properties of the state. On deeper scrutiny, however, these projects are steeped in two problems: Firstly, they showcase the state’s tendency to act in a top-down manner, and leverage a patronising logic. Under this rubric, the state — with its command over capital, technology, and know-how — is seen to exclusively wield the elixir that resolves all societal problems. As a consequence, the society/people for whom development projects are doled out are seen to be mere pliant receivers. Not surprisingly, the unveiling of these development projects has not excited “passions” from the intended beneficiaries across the divide as they do not give primacy to their first-order interests, namely, the demand for peace, justice, and accountability from the perpetrators of this violence. Secondly, the unveiling of these projects has also reinforced the development bias of the state, as, historically, the major chunk of development projects has been concentrated in the valley areas.

One of the unintended consequences of these launches could be the redrawing of structural and ethnic faultlines in the state. The projects could accentuate the unequal access of communities to power and resources. For instance, they may weaken the bargaining power of the Kuki-Zomi-Hmar groups, perpetuate the existing structures — political and economic — of injustice, and reinforce their unequal citizenship.

While PM Modi did not explicitly address two of the principal concerns expressed by the Meiteis, demographic imbalance and free movement, Governor Ajay Bhalla alluded to them in his welcome speech at the Peace Ground at Lamka. He squarely put the onus on the Kuki-Zomi-Hmar people to not allow settlement of “illegal immigrants” in the state. However, it remains the primary responsibility of the state to regulate the movement of population across the border in line with the existing institutional framework. Political leaders and civil society organisations must not be allowed to arrogate this responsibility to relentlessly dehumanise and target a particular community en masse as “illegal immigrants”. Governor Bhalla rightly acknowledged the three formidable challenges facing Manipur, namely, peace, development, and trust. “To heal and help and look forward”, he underscored the imperative to engage in “dialogue, understanding and inclusive governance”.

PM Modi could have seized the political opportunity offered by his long-pending visit to Manipur to elaborate and chart out a clear political roadmap on the mutual complementarity of peace, development, and trust that his able host flagged. In his silence, he revealed his priority on development and setting the political optics right. It remains to be seen whether development can, as Sachs argues, serve as “a myth which comforts societies,” which are already tormented and psychologically bruised by over two years of violence.

The writer is Professor and former Head, Department of Political Science, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad. He is also a Senior Fellow, Centre for Multilevel Federalism, Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi.

Views expressed are personal