Opinion In Bihar, teachers’ bias could be keeping children back

Teachers’ expectations can shape a child’s confidence as much as their grades. Evidence from Bihar shows how subtle perceptions reinforce social inequality

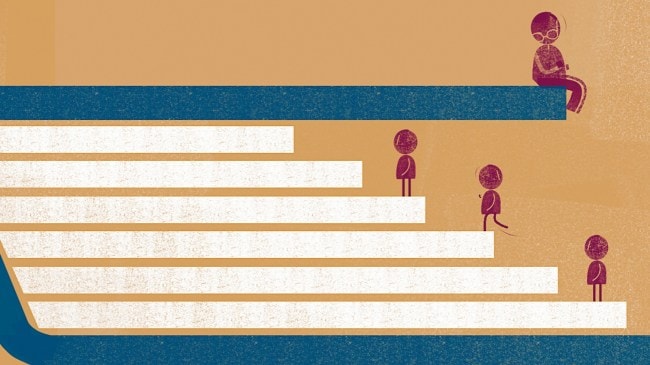

Differential teacher expectations may lead to teachers interacting with students from different communities in varying ways. An upper-caste teacher who believes a backward-caste student has lower learning levels compared to upper-caste students may not invest in the former, once again leading to divergent educational outcomes between students of different castes. (C R Sasikumar)

Differential teacher expectations may lead to teachers interacting with students from different communities in varying ways. An upper-caste teacher who believes a backward-caste student has lower learning levels compared to upper-caste students may not invest in the former, once again leading to divergent educational outcomes between students of different castes. (C R Sasikumar) Also Satarupa Mitra, Soham Sahoo and Ashmita Gupta

As Bihar, where caste often shapes political narratives, heads into another election, it is worth asking how deeply these divisions impact lives. Our research at the intersection of psychology and economic development suggests that the fault lines of social fracture extend to the classroom, reinforcing the very hierarchies that education is meant to dismantle.

Over the past two decades, Bihar’s education spending has increased tenfold to nearly Rs 50,000 crore, resulting in a dramatic expansion of schools and teaching staff. Yet, deep social gaps in learning outcomes persist. Data from the Caste-Based Survey 2022-23 show that only 14 per cent of individuals from the general category have completed Class 12, compared with 9.5 per cent among OBCs and just 6.6 per cent among SCs and STs. The gap widens sharply at higher levels of education, where historically disadvantaged groups remain starkly underrepresented.

The persistence of these disparities reflects a complex interplay of factors — structural disadvantages, economic constraints, and variations in school quality. Yet one often-overlooked dimension lies within the classroom itself: How teachers form expectations about student ability. Think of a setting where you are a teacher and you have a student, who you (mistakenly) believe has lower learning levels. How would your interaction with her be? How often would you engage with her?

Our study, ‘Caste Identity and Teachers’ Biased Expectations: Evidence from Bihar’, undertaken jointly by the Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI) and the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore (IIMB), examines these questions through a systematic empirical analysis. The study collects data from a representative sample of public schools in four districts: Vaishali, Sheikhpura, Purbi Champaran, and Jamui. A rich set of information was collected from 229 teachers and 1,088 students of Grades VI to VIII, from about 105 schools. The students were asked to take standardised tests in Hindi, English, and Mathematics. Independently, their respective teachers were then asked to categorise each student as belonging to the “top,” “middle,” or “bottom” of the class in each subject. Comparing these subjective assessments with students’ actual test scores allowed us to construct a measure of “evaluation bias” — the gap between perceived and demonstrated ability.

We compared how the evaluation bias varied between general category and backward-caste students (OBCs, SCs, and STs) when they were taught by the same teacher. This approach enabled us to estimate whether forward-caste teachers systematically exhibited greater evaluation bias and, therefore, had lower expectations for students from backward castes. Indeed, backward-caste students were systematically rated lower by forward-caste teachers, after accounting for classroom characteristics and grading tendencies. This approach accounts for student, school and village characteristics, and therefore, isolates the “extra disadvantage” that arises when teacher and student caste identities interact.

The results reveal a clear pattern of evaluation bias. Forward-caste teachers rate backward-caste students 0.22-0.43 ranks lower than their actual test-based performance warrants. This translates into a 17-27 percentage point higher probability that a backward-caste student is underestimated compared to a similarly performing peer from the general category. The effect is strongest for students from SC and ST communities. Importantly, there is no evidence that these students perform worse in objective tests, indicating that the bias stems from perception, not performance.

Teacher expectations influence how students see themselves — their confidence, motivation, and willingness to aim higher. When children from marginalised communities are consistently underrated, they internalise these low expectations, which may result in lower effort in the long run, shaping their educational choices, aspirations and life trajectories.

Differential teacher expectations may lead to teachers interacting with students from different communities in varying ways. An upper-caste teacher who believes a backward-caste student has lower learning levels compared to upper-caste students may not invest in the former, once again leading to divergent educational outcomes between students of different castes. Those of us in the profession of teaching are often asked to guard against “teaching to the top of the class”. Our research suggests that the precursor to this belief about who belongs at the top of the class may be systematically biased.

In a state like Bihar, where education remains the most visible ladder of mobility, these belief-driven barriers take on enormous significance. They remind us that reforms in infrastructure, curriculum, or testing cannot substitute for reforms in perception.

While our findings offer rare quantitative evidence on caste-linked bias in teacher expectations, expanding the dataset could reveal a far richer and more nuanced picture. A larger, state-wide study, spanning more districts, rural-urban contexts, and both private and government schools, would help uncover how these biases vary across different institutional settings. Following students over time would reveal whether these perceptual gaps persist as they move through grades, and how such biases shape their confidence, academic performance, and long-term outcomes. In short, expanding the data would shift Bihar from merely diagnosing a challenge to designing effective solutions. It would help identify where interventions can have the greatest impact and position the state at the forefront of evidence-based education reform.

The evidence points to an urgent need for systemic change. Tackling caste-linked perception gaps will require both mindset shifts and institutional reforms. Caste-sensitisation and implicit bias training for teachers can make unconscious patterns of expectation visible and correctable. Data-driven feedback loops, where teachers periodically compare their subjective assessments with students’ actual performance, can recalibrate beliefs. Promoting greater diversity in teacher recruitment, so that it reflects Bihar’s social composition, can help reduce systemic blind spots and foster empathy. Finally, institutional monitoring of grading fairness can promote accountability and ensure equitable assessment practices.

Our analysis does not suggest that teachers consciously discriminate. It highlights how deeply entrenched social hierarchies can shape belief formation, even within professional contexts guided by meritocratic ideals.

Bihar’s progress in expanding access to education is undeniable, but the next phase of reform must focus on equity in learning quality. Understanding how biases shape expectations can help policymakers move beyond physical infrastructure and enrolment toward the subtler but equally critical goal of cognitive equity, which is fairness in how ability is perceived, nurtured, and rewarded.

For Bihar, and indeed for India, the promise of education will only be fulfilled when classrooms become spaces where every child is judged by performance, not perception. No matter which government comes to power, the broader educational policy must acknowledge the debilitating roles of not only the material ramifications of prejudice in the classroom, but also the psychological frictions that enable such prejudicial behaviour to emerge in the first place.

Banerjee is associate professor of economics at IIM Bangalore; Mitra is assistant professor, TA Pai Management Institute, Manipal Academy of Higher Education; Sahoo is associate professor and chairperson of public policy at IIM Bangalore; Gupta is an economist and member secretary at Asian Development Research Institute