Opinion At Central Vista, a flawed decolonisation project by BJP-RSS

Kaushik Das Gupta writes: Despite the Modi government’s claims to root out colonial laws BJP-run governments, including at the Centre, have weaponised the sedition law — once used against nationalists including Gandhi, Tilak and Nehru — to showcase its might against dissenters

Kaushik Das Gupta writes: The Central Vista makeover is touted as a moment of arrival of sorts for the nation -- a long overdue unshackling of the colonial fetters that had prevented Independent India from claiming its place in the comity of nations in true measure.

Kaushik Das Gupta writes: The Central Vista makeover is touted as a moment of arrival of sorts for the nation -- a long overdue unshackling of the colonial fetters that had prevented Independent India from claiming its place in the comity of nations in true measure. There could be two ways to look at the government’s Central Vista project. One, as an intervention to spruce up, or redesign, parts of the public space to make it a more efficient interface between the governed and those who govern. Periodic stock-taking of such crucial avenues and buildings should be par for the course – unfortunately, that did not happen. It’s, however, best that conversations on such initiatives are left to the specialists – architects, planners, historians, economists.

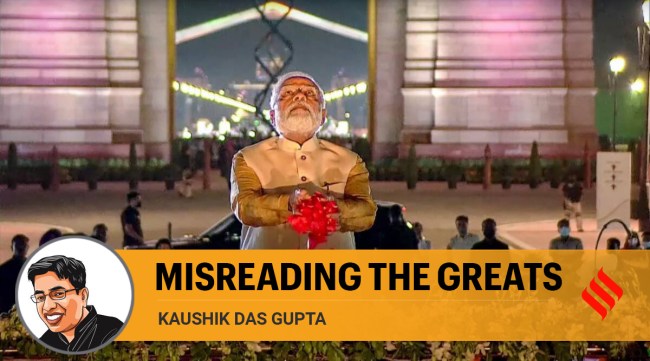

It’s in another aspect that the project has drawn more attention. Like in several of its public policy initiatives, the government has directed a significant part of its energies toward projecting a paradigm shift. The Central Vista makeover is touted as a moment of arrival of sorts for the nation — a long overdue unshackling of the colonial fetters that had prevented Independent India from claiming its place in the comity of nations in true measure.

It says much about the drive of the government – and the lack of creative thinking from the Opposition – that these two strands seem to have become inextricable. That too shouldn’t be surprising: All urban plans, especially those of capital enclaves, have ideological moorings. What should, however, be contested is the course the conversation is taking. In an article in this paper, for instance, BJP Rajya Sabha MP Rakesh Sinha writes of the installation of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s statue at the site as a part of the Modi government’s “determination” to “decolonise” the Indian mind.

Such claims are not new. But Sinha begins his arguments in ways not typical of an ideologue. A respected academic, erudition is writ large in Sinha’s evocation of scholars of varied leanings and persuasions – Tagore, Fanon, K C Bhattacharya, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Namvar Singh – to talk of the “salience of cultural concerns” in anti-colonial struggles.

Moreover, questions about the associations of knowledge systems with the country’s colonial past must be taken seriously. This is not just because – as Sinha says – the issue is “linked to the perception gaps between elites and commons masses (that) exists in almost all post-colonial countries”. The matter requires centerstage in any democratic society because languages are critical to who acquires knowledge, and in what measure. Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s writings have become the go-to-works for post-colonial initiatives not just because the Kenya writer gave up writing in English for the Gikuyu language but also – and more importantly – because he has constantly underlined that vocabulary is crucial to people claiming ownership of resources that are rightfully theirs – in parts of Africa, it has even inspired initiatives for better healthcare facilities.

The salience of “decolonisation” cannot be overstated in resolving post-colonial predicaments — including in India––as diverse as addressing learning deficits to evolving ecologically-sustainable methods of natural resource governance.

Sinha’s evocation of wa Thiong’o to make a case for the “indigenous” in his introductory paragraph, therefore, arouses hope that the scholar from the Sangh Parivar can help turn the discourse on Central Vista to conversations on knowledge systems that have eluded India because its intellectual elites have been “feeble” decolonisers. Perhaps a bit on wa Thiong’o or Fanon-inspired resistance movements or transformations. Or whether Bose – now enshrined at the Central Vista – would have been a more potent decoloniser than Nehru or Gandhi?

The article belies that hope. The ideologue seems to be doing most of the talking. Sinha cites the eminent critic Namwar Singh’s lament on the “missing attitude of militant decolonisation” and then devotes paragraphs on PM Modi in ways no different from several of the hagiographic content churned by his peers in the BJP – perhaps somewhat at odds with his parent organisation RSS’s disavowal of the personality cult. The article makes no bones that the PM’s “decolonisation project has a clear and focused target”.

A few sentences from Namwar Singh’s essay where he talks of the lack of militant decolonisation would be relevant here. “Among Indian writers after Independence, the attitude of militant decolonisation which was to be seen in the writers of an earlier generation has grown feeble and slack,” is what he actually writes. But that’s beside the point. What begs for more creative interpretation from Sinha are Singh’s words of caution in the same essay. “How should we oppose the new onslaught of colonisation? With our tradition? But which tradition? Tradition itself is a reconstruction: The rediscovery of the past by the present as desired. The colonialists of yesterday and the imperialists of today are presenting an image of our past which is primitive and chiefly an index of our backwardness. And closer at home, the tradition presented by Hindu fundamentalists is something else altogether, something extremely one-dimensional and narrow” — prescient words given that a large body of scholarship has argued that the notion of an Indic civilisation cannot be divorced from the works of Orientalist scholars.

Like Sinha, Namwar Singh too draws from wa Thiong’o – even in the title of his essay, ‘Decolonising the Indian Mind’. But in the questions, he asks, the critic is inspired by the African writer’s call to resistance in ways that are at odds with the BJP ideologue: “If we were to pit an image of our nation against colonialism, whose nation would it be? The nation of those who hold the reins of the state? But what then will be the nation of those who feel oppressed by the state and want to change it? For how long a Dalit can go on sacrificing his identity for the identity of the nation?”

In the late 1970s, wa Thiong’o was arrested in the middle of the night by the Kenyan government and spent a year without trial or sentencing in prison, writing on toilet paper supplied by the prison authorities. He has lived in “exile” for close to 40 years — alerting us to the authoritarian tendencies that have marred the tryst of large parts of Africa with decolonisation and reminding us about colonial legacies that stifle dissent.

In 1945, Nehru donned the lawyer’s robe to join the defence team for the INA officers charged under Section 121 of the IPC for waging war against the nation. However, despite admitting to problems with the sedition rule, his government persisted with the colonial era-law – here Nehru indeed fits Sinha’s bill of a “lazy decoloniser”. But despite the Modi government’s claims to root out colonial laws — according to Sinha, it has done away with several of them – BJP-run governments, including at the Centre, have weaponised the law — once used against nationalists including Gandhi, Tilak and Nehru – to showcase its might against a range of dissenters, including young adults.

Conversations on decolonisation must go on. But they must be about addressing the core concerns of expanding democracy, central to arguments of scholars like wa Thiongo. A great disservice is done when it becomes an exercise in identity politics, and worse still, hagiography.

kaushik.dasgupta@expressindia.com