Opinion BSP cannot be ruled out as a contender in UP polls

Badri Narayan writes: It retains the support of its voter base, has been working hard on the ground to build social alliances.

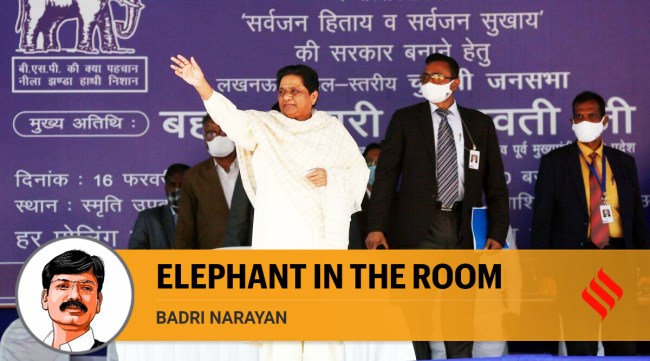

Bahujan Samaj Party chief Mayawati holds an election rally in Lucknow. (Express Photo: Vishal Srivastav)

Bahujan Samaj Party chief Mayawati holds an election rally in Lucknow. (Express Photo: Vishal Srivastav) Recently, while discussing the 2022 UP Assembly election at a Dalit basti in central UP, I mentioned that the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) was missing in the campaign. A Dalit boy responded with a revealing anecdote: “An old woman in a village had three sons. For certain reasons, she did not like the youngest and treated him badly. So, everyday, she would prepare thalis only for her two favourite sons. After serving the food, she would go to the well to fetch water. This was when, each day, a miracle would occur. The two thalis that she served would automatically create a third thali of food.” The BSP is in a similar situation, the boy added: “Even if no one wants to focus on us and recognise us, they can’t ignore our existence. And they will not be able to deny our existence in the future, either.”

Most of the media as well as political analysts are projecting the UP assembly election as a bi-polar contest between the BJP and the Samajwadi Party (SP). They don’t consider the BSP a contender for office this time. Even those who acknowledge the party’s presence on the ground argue that its impact on the outcome is likely to be minimal.

It is true that the BSP has lost the perception battle, but on the ground, it is turning the contest triangular in several constituencies. There are three reasons for this. First, the BSP’s base vote is mostly intact. The Jatavs, who are estimated to be 11 to 12 per cent of the UP population, remain a cohesive force. Most of the Jatav youth are working as BSP cadres. The Jatavs are nearly two-third of the Dalit population in many districts. While it may be true that some non-Jatav Dalit castes will vote for the BJP and SP, a sizeable number of them may back the BSP.

Second, the BSP has distributed tickets as per the caste and social formula that helped the party in the 2007 assembly election that it won. This formula is based on building an alliance of Dalits, MBCs, Brahmins and Muslims within the broader framework of “sarvajan” politics. However, this formula may not be effective this time as Muslims are likely to vote strategically for the party best placed to defeat the BJP. The Brahmin vote may also not split to the extent of favouring the BSP as it did in 2007. Still, the voting percentage of the BSP is unlikely to slide below the 2017 level — it polled 22.23 per cent vote in that election.

Third, as this election is being held in the backdrop of the pandemic, cadres and an aggressive social media presence may matter. BSP cadres have worked all year to reach out to their voter base by organising small meetings and door-to-door campaigns. The BJP and the BSP are the two parties with a strong cadre base in UP. In this election, the party that is able to draw its voters to the booth may emerge as the stronger one. The BSP won’t lag behind on this.

Compared to the BSP’s 22.23 per cent vote in 2017, the SP got only 21.82 per cent of the vote. But as the BSP did not kick off a big rally-centred campaign early enough this time, the media has made out that the fight is a bipolar one between the BJP and the SP. They miss the point that the BSP’s cadres and support base do not need big rallies, although these are needed for attracting non-base votes. With Mayawati starting to campaign aggressively, the BSP seems to be recovering lost ground and seems to be dividing the votes of various non-Dalit communities in its favour. The local BSP cadres describe these votes as “phata hua” (divided). They say that these votes, which may come from both the MBCs and upper castes, are the party’s strength in this election. Moreover, the BSP organisation is working hard, especially in the reserved seats. The party has also opened digital war-rooms and has become more active on social media with online campaigns and digital rallies.

The BSP can influence the result in two ways — it can divide many social communities that are perceived to be sympathisers of BJP or SP. By forcing a triangular contest in many constituencies, the BSP may either reduce the margin of victory of the candidates of the two main contestants or even win them.

The way this election is proceeding, analysts and psephologists who are giving the BSP 3 to 12 seats and around 11-13 per cent vote share may have to review their perception of the party as a marginal force in the electoral discourse.

This column first appeared in the print edition on February 19, 2022 under the title ‘Elephant in the room’. The writer is professor at the G B Pant Social Science Institute