Opinion At the heart of a film about Partition and exile, a river called Subarnarekha

On one level, ‘Subarnarekha’ is about the ‘refugee problem’; a recognition of how livelihoods, homes, identities, and human connections in the old country are lost and must be recreated. This is equally relevant today

Ghatak resists any tidy resolution. For Ishwar, the traumas of Partition may be insurmountable. But little Binu may be the bearer of hope and possibility, and the film’s haunting ending may signify a promise of new beginnings.

(Wikipedia)

Ghatak resists any tidy resolution. For Ishwar, the traumas of Partition may be insurmountable. But little Binu may be the bearer of hope and possibility, and the film’s haunting ending may signify a promise of new beginnings.

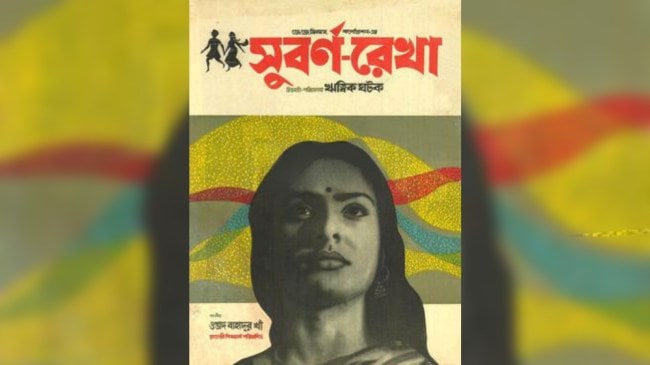

(Wikipedia) The birth centenary of Ritwik Ghatak this year is being widely commemorated in print, through special screenings of his films, and through memorial lectures and debates. This year also marks the 60th anniversary of the release of his best-known film, Subarnarekha. Part of his Partition trilogy, it was not a commercial success. However, it often appears on lists of the greatest films of all time, and it is speculated that had Ghatak released his masterpieces before Ray’s Pather Panchali in 1955, he could have occupied the undisputed pre-eminent position in Indian parallel cinema. In art, as in life, timing is all.

In Subarnarekha, the plot, so full of Ghatak’s intentional use of coincidences and melodrama, follows the protagonist Ishwar Chakraborti, a man who has arrived as a refugee in Calcutta after Bengal’s Partition, and who is trying to cobble together a family with his much-younger sister Seeta, and Abhiram, a poor lower-caste boy he has taken in. Ishwar takes up a job in Chhatimpur on the banks of the Subarnarekha; the years go by, Seeta and Abhiram grow up, fall in love, and elope against his wishes. They set up home in Calcutta, and have a child, Binu. One fateful night, Abhiram is lynched by a mob. The widowed Seeta finds herself in a brothel. Ishwar spends a nightmarish evening in Calcutta in an alcohol-fuelled haze, ending up at the same brothel. He is to be her first client. Recognising him, she slits her throat. Ishwar returns to Chhatimpur with Binu. He is dismissed from his post and has lost everything, his sister, Abhiram, his job, his future.

Epic in scope, and dense with events and characters that cry out to be excavated and understood, this masterpiece of world cinema is replete with timeless themes: Exile, displacement, loss, the meaning of home and nation, caste, social inequality, family strife, the attempts to build a new India, and the seeming impossibility of finding happiness. At the heart of the film is the river itself, the grand amphitheatre and dramatic setting for the personal tragedies that will unfold. Here, we are faced with the immensity of a wide, slow-moving river, huge boulders, treeless plains, vast alluvial sands, an arid landscape, the indifference of a pitiless sky, all suspended in an unchanging geological time. The entire film is permeated by a sense of foreboding. Despite some transient moments of happiness, the pervasive mood is one of a profound unease, of disquiet. There is no consolation to be found here.

Ghatak’s intention was clear. In his writeup entitled On Subarnarekha, he stated: “What I felt and wanted to tell through my film is the story of the present economic, political, and social crises in Bengal.” Further: “While I do not seek to practice passionate sloganeering, I also hate to make films only to capture ‘human relationships’.” As a lifelong Marxist, he firmly placed the personal against the larger backdrop of sweeping political conflicts and ideologies. On one level, this is a film about the “refugee problem”; a recognition of how livelihoods, homes, identities, and human connections in the old country are lost and must be recreated. This is equally relevant today; by April, a record 122 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced due to conflicts and persecution. But Ghatak also clarified that “refugee or homeless in this film does not mean only the homeless from East Bengal. I wanted also to speak of the fact that we have all been rendered homeless in our time, having lost our vital roots.” In other words, we are all refugees now.

The film ends in an ambiguous denouement. Having lost everything, Ishwar is walking with Binu towards the promised home, on the other side of the river, where the blue hills, the “neel pahad” that Seeta had sung of, beckon. Ghatak resists any tidy resolution. For Ishwar, the traumas of Partition may be insurmountable. But little Binu may be the bearer of hope and possibility, and the film’s haunting ending may signify a promise of new beginnings.

The writer is a former IAS officer