The Why Chromosome

An Indian sons search for his Pakistani father and his Muslim legacy

An Indian sons search for his Pakistani father and his Muslim legacy

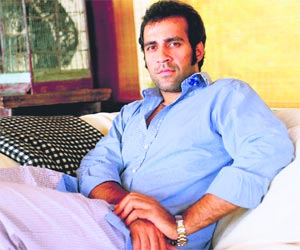

Part memoir,part journalism,Aatish Taseers Stranger to History is a brave book. It is also extremely significant because it heralds the long-required candour among young,more adventurous authors who do not hesitate to lay bare family secrets,especially if they help understand a greater phenomenon. For Taseer,the clear starting point of the book is the search for his identity: the anomaly of a Muslim with a Pakistani father growing up in a Sikh family in India.

The actual unbridgeable divide which separates his parents,living in different countries,is symbolic of Partition,and its tragic ramifications. It is a schism Taseer is not comfortable with and the absent yet indifferent father makes the pain even more acute. The fact that his father apparently feels neither guilt nor remorse that he had abandoned his child becomes a recurring theme in the book. In fact,it is only after Taseer has written an article about Pakistan and the London bombings that his father is driven to acknowledge his son,and that too,to chastise him severely. There is a peculiar mendacity in the relationship which Taseer pushes to a larger political level,ie,obvious parallels are drawn between Pakistan holding India responsible for all its ills and declining international status. This is where the significance of the book begins to blur. Is this the story of a child spurned or is this real politic? After all,this is also a deeply disturbing story of a child,who is a stranger both to his Muslim legacy and his own personal history. The confusion becomes greater when the latter viewpoint begins to obscure the journalistic quality of the book,which indeed is far more revealing and detailed than the personal story. However,the thinly glimpsed emotional history is often allowed to dominate and so we do not even see a reproduction of the so-called incendiary article that pushed Taseer senior to upbraid his son.

The most interesting parts of the book are his meticulous observations of his travels through Turkey,Syria,Saudi Arabia and Iran,opening up a world of curious religious discomfort when the state imposes a lifestyle. In his search for the Muslim identity,he reproduces detailed discussions with religious ideologues as well as lush cameos of bars,homosexuals and irrepressible women who fight back tyrannical regimes. Some of the acute comments come in small doses such as the Hindu tattoo which he has to cover up when he goes for Haj,or the encounters he has with the Hare Krishnas in Iran. There are moments of sheer terror,as well as when he is put under surveillance in Tehran and subjected to rigorous questioning. However,occasionally,the same insensitivity which he applies to his larger family appears here as well. For instance,when he throws in a one-liner about defiant women living under oppression,dismissing them as addicted to confrontation,he doesnt understand the sheer courage with which they operate and why the high-pitched rebelliousness is essential to give them the adrenalin of bravery.

Ultimately,this is a book to be recommended because of the unusual quality of its subject matter and its undaunted search for the cultural Muslim which Taseers father claims to be. The personal story,on the other hand,deserves another,more thoughtful book,and one in which Taseer junior should be encouraged to give us a closer look at the people who made him. But next time,perhaps,with a little more insight.