The Missing Person is Back

After 36 years,Adil Jussawalla has come out with a new book of poetry

Forty years on,with the forest gone my sights improved

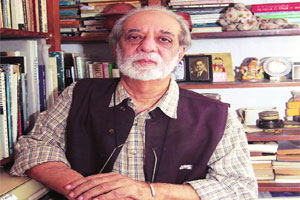

His writings can barely aim to occupy a corner of a bookshelf two books of poetry and an anthology of Indian writing. But numbers are no measure of the importance of Adil Jussawalla,each of whose works have marked significant moments in Indian poetry,utterances that resonate through the flow of time and ripple out into the works of future poets. His first book of poetry,Lands End 1962,announced a formidable modernist at 22. His second,a powerful and bleak sequence of poetic fragments Missing Person,1976,gave angry voice to the crisis of the urban Indian poet writing in English: the poet as the missing person,the blank in a literary culture that made no place for him,hobbled by a language that carried the stain of colonialism and class privilege.

slim volume of poetry just published by Almost Island,is the fruit of

that years vision and revision. The first section of the book revisits the time Jussawalla was a young architecture student in London in 1957,17 years old and impressionable in a great foreign city in which one felt small but excited to be in. He skimped on meals to buy books and was invigorated by its cultural scene,and came to realise that architecture was not his calling. It wasnt as if I didnt enjoy architecture. But I had no time to write. I kept a journal before I went to England and I could not seem to find time for it. I missed the release of writing. B y the end of my first year in architecture,I had decided to quit and had some sort of a nervous breakdown, says Jussawalla,now 71 years old. This period of loneliness was when he began writing poetry seriously,including the poems which went on to become Lands End.

London is a melancholic landscape in Trying to Say Goodbye,of sudden silences,misty mornings and broken,lonely people. The poems that came from that area of memory have a young mans perspective; they are about people and objects that spoke to me then8230;Some of those characters continued to haunt me,they appear in Lands End,and in this book, he says. These are ordinary people as indeed are the many poets,drunks and wanderers in this collection touched by the poets eye. Jenny,a street painter without talent who is transmuted into something fleetingly beautiful; Baglady Anna,a mountain moved without faith,and Hong Kong Lee kitchen worker,/forced to set up house/on the bad side of the Thames,/river that smells of slaves.

His experience in England and its contrast with life in Bombay also stirred the political consciousness that marks Missing Person. There was a lot of talk of racism,of experiences that friends went through,and one began to develop a social and political perspective on oneself. One didnt have that while living in Bombay,where one was more privileged. To put it simplistically,you could take a flight across countries,and go from being oppressed to oppressor,in a matter of a few hours. Because the inequality and poverty here is so horrendous. In Missing Person,I was trying to deal with these dual perspectives of a person in my class,as well as the issue of language,of using English, he says.

In a lecture delivered in Singapore in 1986,Jussawalla spoke of realising his precarious position as an English language writer,affected by works in English produced in whatever country the language is spoken and written during a conversation with Hindi novelist

Nirmal Verma. He offended me a little by saying that I couldnt have any idea about any kind of young Hindi writer who came to him with his work and what his problems were. I replied with some heat that I didnt see why that writer should be any different from young writers in Bombay and why his problems should be so very different either. Verma came back with great vehemence. They are different because they write and talk only in Hindi, he said. They dont know a word of English!. Vermas reproof notwithstanding,Jussawalla was one of the first thinkers and editors attuned not just to the politics of language but also the necessity of a conversation between the many literary cultures in India. Long before it became fashionable,New Writing in India,the anthology he edited in 1974,brought together writing in

11 Indian languages by striking literary voices,from Bhalchandra Nemade to Qurratulain Hyder,Badal Sircar to MT Vasudevan Nair,Nissim Ezekiel and Benoy Majumdar.

If Trying to Say Goodbye lacks the fierce anger and panic of Missing Person it is more intimate in tone,and leavened by a wry humour it is because of the distance he has travelled. I may be wrong but I believe Ive found a way out of the panic and anger. My identity and the identity politics that accompanied it matter much less to me now than they did when I wrote Missing Person. I accept a marginal identity and feel compelled to celebrate it, he says. Thats partly because,he says,there always have been poets who have been on the outside of things. Perhaps one needs to explore why there are poets who need to feel marginal,otherwise they wouldnt write at all, he says.

Poets find themselves on the cramped margins of the literary culture in India largely because of an acute lack of publishing avenues. It was the case too in the 1970s,when Jussawalla had just returned to India. In 1976,he became a part of a short-lived but landmark experiment in Indian poetry: Clearing House,a publishing collective formed by poets Arvind Krishna Mehrotra,Arun Kolatkar,Gieve Patel and Jussawalla. We set up Clearing House because there were lots of unpublished manuscripts to clear ours and those of other poets. We set up a mail-order service. Funding came mainly from pre-publication orders. That worked for a while. On a couple of occasions,the poets wed agreed to publish had to chip in with funds too, he says. Till 1984,when it folded up,Clearing House brought out eight books,lovingly designed by Arun Kolatkar,among them Gieve Patels How Do you Withstand,Body; Jussawallas Missing Person; Mehrotras Nine Enclosures; and Kolatkars Jejuri. They got to be read by thousands of people,in

India and in different parts of the world. I think thats success.

For young poets today,Jussawallas advice remains to do what it takes,despite the discouraging history of small presses and literary magazines: You might find yourself having to raise funds and publish yourself. This is not vanity publishing,there is no other way out, he says. But that does not make him very optimistic about the future of Indian poetry,which he once described as a house of cards,a perishable empire. Until we have even a few publishers committed to keeping our most interesting writers in print,until we have more critics who can enrich the idea that we have a long-standing literature,more than 200 years old,not just individual living writers and the many dead ones who are out of print and this may never happen the edifice will continue to appear ephemeral,doomed to the passage of time,shaky. Nevertheless,

poets will keep writing. Because,as he says in Watch Your Step,Old Man: saying it/saying it/was our way of keeping balance./It was everything else that kept falling like glass around us.