This racket about duties

Chandan Basu is not the only one who may want to avoid paying high customs duties on cars. Anybody who wants to own a car would like to do s...

Chandan Basu is not the only one who may want to avoid paying high customs duties on cars. Anybody who wants to own a car would like to do so. After all, the first principle of economics is that people respond to incentives. In this case, the structure of customs duties in India provides an incentive and a framework to avoid duties. Of course, the higher the duty, the greater the incentive. That is why the car racket operates for makes like Lexus, Mercedes, Jaguar and BMW which cost between Rs 80 lakh and Rs 1.5 crore.

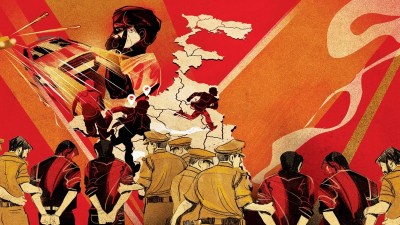

In the spirit of reforms, the 8220;peak rate8221; of customs duty, which applies for almost all manufactured goods, has dropped from 150 per cent in 1991 to 15 per cent in 2005. But the term 8220;peak rate8221; is incorrect. There are so many products with an above-8221;peak8221; rate, that it might better be called a 8220;median rate8221; for manufactured goods. In the case of imported cars, the rate is at the shocking level of 105 per cent. The prevalence of such high rates makes India look foolish when we claim that our 8220;peak8221; rate is 15 per cent. When a customs duty is 105 per cent, there is an incentive to bypass it. If criminals become involved in the trade, no one knows where they will stop.

The first reaction of the government will be to clamp down on customs duty evasion using policemen. But gold smuggling did not go down by the police chasing smugglers. It went away when Manmohan Singh and Chidambaram reduced customs duties. Lower tax rates change the cost-benefit calculations of evading taxes. If the customs rate on imported cars had been 15 per cent there would have been much greater compliance. However, in the name of protecting domestic industry, which ironically consists primarily of foreign manufacturers such as General Motors, Ford and Honda who are among the biggest in the world, India keeps customs duties rates on cars nearly 7 times the 8220;peak rate8221;. Moreover, India today is an exporter of cars. There is no reason to think the industry needs protection.

Even if the customs duties on all imported cars had been 105 per cent, it would have been one matter. Here, the issue is further complicated by the fact that when two identical cars are imported into India, they encounter very different tariffs. This is because there are a large number of exemptions. These exemptions are based on who is importing, or why he is importing. Under the Export Promotion Capital Goods EPCG Scheme, import of motor cars, sports utility vehicles and all purpose vehicles by hotels, travel agents, tour operators or transport tour operators whose total foreign exchange earnings in the current and preceding three years is Rs 1.5 crore, are exempted from paying the normal 105 per cent customs duty, and have to pay only 5 per cent.

Rules allow items to be imported for defence, police, training, education, oil exploration, exhibitions, expeditions, for export purposes such as packaging materials, durable containers, by charitable institutions, for handicapped persons or for sports related activities8212;exemptions from customs duty after due paper work. The list of items where such exemptions exist runs into nearly 2000. The importer gives the appraising officer the relevant literature and a certificate from one of the 33 approved certifying agencies such as the Director General of Foreign Trade, the Director of Vanaspati, Vegetable Oil and Fat, the Council for Leather Exports or the Sports Authority of India.

The importer has to get a Bill of Entry from the appraising officer. These steps involve multiple contact points with the government, and huge costs of compliance, since appraising officers have to get engaged in questions of valuation and end-use. This means that even when the importer does not have a genuine business, as is alleged in the case of Sanjay Bhandari, the man Chandan Basu is reported to have bought or leased his car from, it is possible for him to bribe his way to the required exemptions.

What is really required is not the police going after those who find loop-holes in the structure of customs duties, but to change this structure. As long as the law is unchanged, the practice will continue, as did gold smuggling until the duties were changed. The minimal agenda in reforms is the elimination of exemptions, which should ensure that no two consignments of a given product encounter different taxation rules or procedures. This would also serve to remove the involvement of agencies such that those which certify end-use. It will remove the involvement of customs officers who can today choose who qualifies for the exemption and who does not.

The second issue in reforms is identifying all goods with a rate above the peak rate and bringing them down to the peak rate. This will reduce the incentive for evading or avoiding duties, especially since we are progressively moving towards reducing tariffs every year. India should be able to truthfully say that the peak rate is 15 per cent.

The third issue is the removal of rate dispersion. The structure of tariffs is presently biased against consumer goods. The duties on raw materials, intermediate inputs and capital goods are generally lower than that on final products. It is on this basis that cars imported under the EPCG scheme face a lower tariff rate when classified as capital goods, and a higher rate when classified as consumer goods. Since modest differences in apparent tariffs can imply very big differences in the effective rates of protection for manufacturers, this results in immense lobbying by firms, in this case the car manufacturers. A uniform rate is the best way to avoid this lobbying.

Deficiencies of domestic taxation, however, pose an impediment against the move to a uniform rate. As a compromise between the first best solution of one rate and what exists at present, the Kelkar Task Force Report suggested that duty rates should be 5, 8 and 10 per cent for 8220;raw materials8221;, 8220;intermediates8221; and 8220;finished goods8221; respectively. Once a proper GST is in place, the next phase of tariff reform can commence, of moving to a uniform rate, and of going down to a uniform rate such as 2 per cent.

So even though the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence may presently be on the job, the one who really needs to act to avoid such cases is Chidambaram himself. He did it for gold, now he should do it for cars.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05