Wearing colourful tights, their foreheads smeared with three strokes of white ash and a tilak, sisters Purva Shivram Kinare and Prapti contort and bend in seemingly impossible ways, rhythmically moving to the beats of a Bollywood number. In front of them, over a dozen officials — judges, jury members and a stage manager – peer closely into their laptop screens at this display of stunning flexibility.

Purva, 24, and Prapti, 22, are yogasana athletes, practitioners of one of the youngest competitive sports at the 38th National Games in the Uttrakhand town of Almora. Ahead of the sporting event, yogasana and mallakhamb (yoga-like postures done on a vertical pole or rope) were classified as demonstration sports by the Indian Olympic Association (IOA), but were later listed as medal sports. This is yogasana’s third straight appearance at the National Games as a medal sport, after the 2023 and 2024 editions.

Over the last couple of years, yogasana, an activity hitherto confined to community parks, homes, yoga studios and smaller, local competitions, has gained a sharp edge. Recognised as a competitive sport in 2020, Yogasana Bharat, the governing body of the sport in India, attained associate membership of the Indian Olympic Association in 2021.

India is also making a pitch for yoga, along with Twenty20 cricket, kabaddi, chess, squash and kho kho, to be included in the 2036 Olympics that the country hopes it can host. Incidentally, at the Paris Olympics in 2024, yoga sessions were held at the Louvre. For the first time, the Asian Games to be hosted at Aichi-Nagoya, Japan, next year will feature yogasana as a demonstration event.

Sisters Purva Shivram Kinare and Prapti, qualified engineers, have won multiple medals at the National Games, since Yogasana was included at the 2023 edition in Gujarat. (Special arrangement)

Sisters Purva Shivram Kinare and Prapti, qualified engineers, have won multiple medals at the National Games, since Yogasana was included at the 2023 edition in Gujarat. (Special arrangement)

The sport has a popular brand ambassador, too, in yoga guru and businessman Baba Ramdev, who, besides heading Yogasana Bharat, is the founding president of World Yogasana, the body dedicated to promoting yogasana as a sport globally.

Yogasana, in its sport form, is rigorous, and full of verve, far removed from the stretches and pranayama that it is popular for. The giant marquee tent at the HNB Sports Stadium in the heart of Almora – where Purvi and Prapti are competing in the artistic pair category – has a modern sports arena feel to it with a doctor’s room, lounge for athletes, a warm-up area, a designated space for technical officials and anti-doping officials, strobe lights and giant screens.

The sisters represent Maharashtra, one of the 22 states that have together sent 171 yoga athletes to the Games. Haryana topped the tally at the Games with six medals, followed by Uttarakhand and Maharashtra with five each and West Bengal with four.

Story continues below this ad

From the mat to the arena

Until half a decade ago, the sport had no centralised governance system; instead, over 200 disparate yoga associations across the country functioned parallelly, holding demonstrations and small-scale competitions.

A pair of Yogasana athletes compete in the Artistic Pair event at the 38th National Games in Almora. (Special arrangement)

A pair of Yogasana athletes compete in the Artistic Pair event at the 38th National Games in Almora. (Special arrangement)

It was in 2020 that World Yogasana set the ball rolling to bring various yoga factions under one umbrella. That, along with the government’s recognition of yoga as a competitive sport, meant that yoga would make a giant leap to match the most complex of its asanas.

For yogasana’s new avatar as a sport, an updated and clearly defined points system for each asana was created, athletes started to compete in gymnast-like leotards and the size of mats were standardised.

Jaideep Arya, secretary of World Yogasana, credits Ramdev for expanding the scale of yoga by “catching them young”. “Earlier, people would come to yoga after the age of 30, if they have ailments, but that has changed. Now, there are thousands of athletes between the ages of 8 and 10. We have aspirations to reach the global stage and have set our eyes on the Olympic pathway,” says Arya.

Story continues below this ad

Sports-quota jobs for medalists at the National Games, too, contributed to the allure of yogasana, moving it away from the confines of a fringe sport and closer to the mainstream.

A teammate helps a Madhya Pradesh competitor with the make up before competition. (Special arrangement)

A teammate helps a Madhya Pradesh competitor with the make up before competition. (Special arrangement)

Plans are afoot for a yoga league, to be officially announced in March, with the first edition scheduled for October-November this year. “Private players and universities have shown interest in the 12-team league,” adds Arya.

Though Ramdev is one of the most recognisable faces of yogasana, Arya also credits other imminent yoga practitioners for throwing their weight behind the sport – among them, H R Nagendra, a yoga therapist and founder-vice chancellor of the Bengaluru-based Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana University, and spiritual leader and Padma Bhushan awardee Kamlesh D Patel.

Arya says Rishikesh-based American yogaphile, Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati, will be brought on board to push yogasana’s global expansion.

Story continues below this ad

“This is the third edition of yogasana at the National Games. After the government officially recognised yogasana as a competitive sport in 2020, there has been a boom, not just in India, but globally too. Over 12 countries, including Zambia and Tanzania, have conducted their national competitions,” says Rohit Kaushik, an executive committee member of Yogasana Bharat.

Over 5,000 registered athletes and 350-plus technical officials are listed on the Yogasana Bharat website.

Uttarakhand is an early mover, with the state government last year announcing plans to become the first state to implement a yoga policy. While Haridwar and Rishikesh are yoga hubs, Almora is not far behind. The National Games venue is walking distance from the Soban Singh Jeena University, a popular learning centre in Kumaon that offers PG Diploma, BA, MA and PhD courses in yoga.

Naveen Chandra Bhatt, the head and convener of the Department of Yogic Science at the university, says seats for all courses are getting filled up. The first course, PG Diploma, was introduced in 2005 in the university’s Almora and Nainital campuses. “In the beginning, we had 40 seats for PG Diploma. Two years later, we started MA and kept adding courses. PhD courses began in 2017. Today, we have 350-plus seats for ALL courses,” Bhatt says.

Story continues below this ad

Aarti Pal, Assistant Professor (Yoga Science) at the University of Patanjali in Haridwar, insists yogasana has the credentials to match sport climbing and breaking, two new sports added to the Paris Olympics last year. “Yoga is no longer associated with senior citizens in a park. The youth are coming to participate in yogasana in droves; asanas have competitive forms. It’s an attractive sport, beneficial for both the mind and body. Songs complement asanas and synchronisation is key, and athletes work on strength, agility and endurance. So why not yoga at the Olympics in the future?” Pal asks.

A complex scoring system

Gymnastics-like in its presentation, minus the high somersaults and flips, yogasana’s modern version induces jaw-dropping awe as athletes stretch, twist and end up in the knottiest of positions.

At Almora’s HNB Sports Stadium, where the artistic pair event is underway, physios, coaches and managers, who have travelled with the teams, stand outside the playing area, intently watching the participants.

Costumes matching with the theme of a performance, for example Shiv tandav, helps a competitor win points. (Special arrangement)

Costumes matching with the theme of a performance, for example Shiv tandav, helps a competitor win points. (Special arrangement)

The officials use a complex point scoring system to rank the athletes – face make-up, expressions, smart themes and imaginative designs on costumes earn points, while human pyramid formations take difficulty levels a notch higher. The greater the area the athletes cover on the mat or field of play, the more the points.

Story continues below this ad

At the Games, yogasana has clearly defined events: traditional, artistic single, artistic pair, artistic group and rhythmic pair. There are at least five categories: forward bending, backward bending, body twisting, leg balance and hand balance.

Athletes in the artistic pair event that Purva and Prapti are competing in must complete 10 different asanas each. Rhythmic pair participants, on the other hand, must choose the same asanas. The number of judges also vary, 10 in traditional and up to 13 in artistic.

The fledgling sport already has its stars. Purva and Prapti, both engineering graduates from Ratnagiri in Maharashtra, have won multiple National Games medals, across categories.

Purva recently hit the headlines when she was nominated for the prestigious Shiv Chhatrapati Award, Maharashtra’s version of the Padma awards. “Yoga was recently added to the sports category for the awards. When Purva receives the award later this month, it will be a major moment for our indigenous sport,” say Purva and Prapti’s coach Ravi Bhusan Kumthekar.

Story continues below this ad

The sisters train for over five hours a day, every single day. “Missing even one or two days of training can set you back by weeks in terms of flexibility and strength. We think like modern athletes,” says Purva.

The sisters, who have opted for a Shiv Tandav theme for their artistic pair event, are now moving to the soundtrack BamBholle from the Akshay Kumar-starrer Laxmii. Their jerseys have tiger skin prints and feature images of Lord Shiva. Shades of red are prominent, too, to match the colour of the sari of the Bollywood star in the song.

“A lot of research goes into a three-minute performance for an artistic pair. This year, the theme is Krodh (anger); last year when we won gold, the theme was Radha and Krishna,” says Purva.

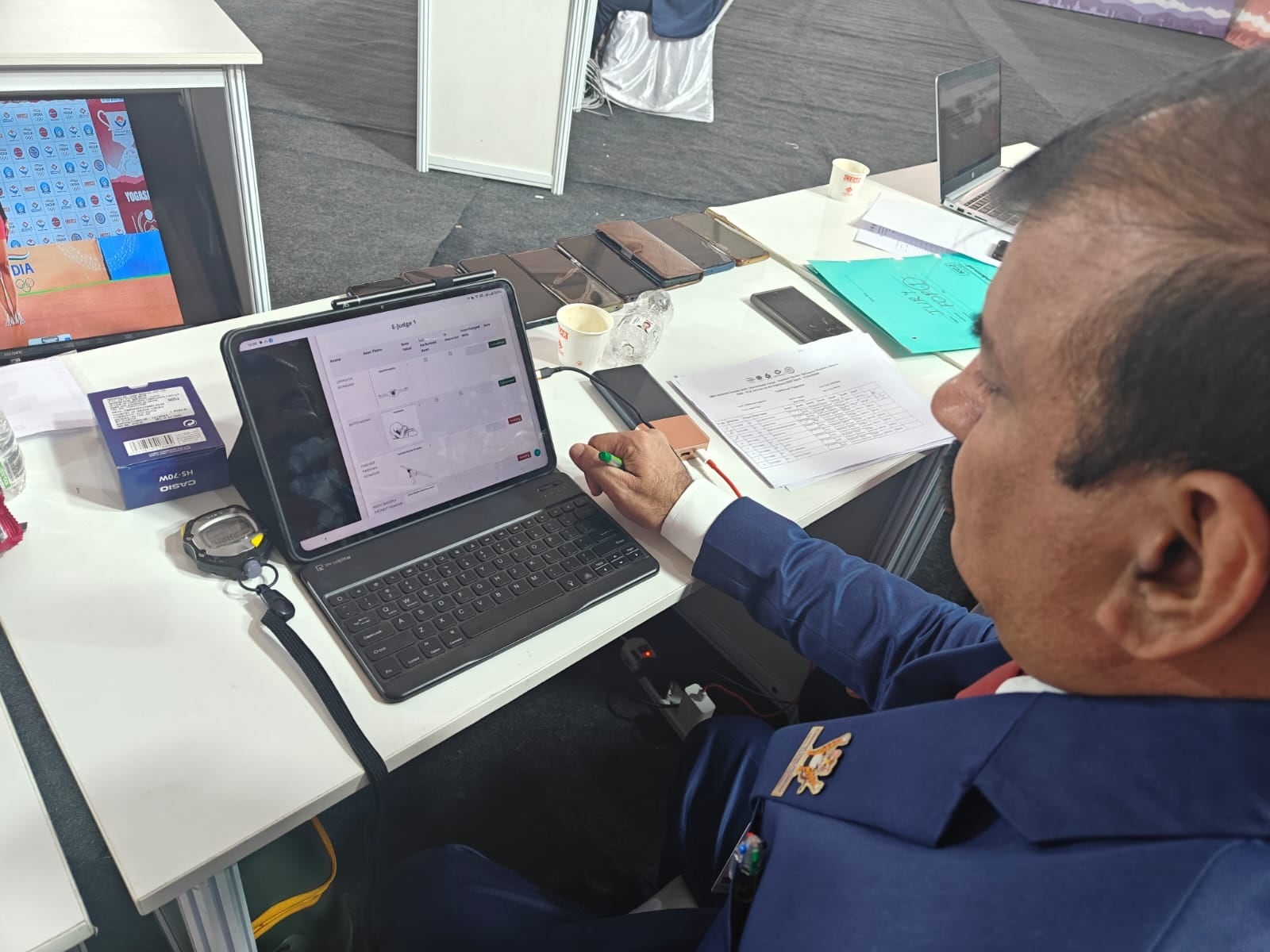

A modern yoga judge uses a laptop to punch in points on a specialised software that displays asanas. (Special arrangement)

A modern yoga judge uses a laptop to punch in points on a specialised software that displays asanas. (Special arrangement)

Judges are hard to please, says Shreyas Markandeya, a sports consultant of Yogasana Bharat. “You can’t smile if your theme is anger-based, for example. If a pair is performing Shiv tandav and their costume reflects that, then they earn points. But if you wear a costume that reflects Ganesh ji vandana instead, the judges won’t be impressed and the points will be docked,” says Markandeya, adding that while the music can be devotional, patriotic or film songs, the lyrics “must contain no vulgarity”.

Story continues below this ad

“No point can be won easily. A lot of effort, hard work and hours of practice are needed to win a medal. The judges watch each and every thing. One slip can end up making the difference between a medal and returning empty-handed,” says Purva.

Like the sisters, Indu Mathuria and Kanika, 21-year-olds from Moradabad, are competing in the artistic pair category. Students of an all-girls gurukul, they are aiming to win their first medal for Uttar Pradesh in their maiden appearance at the National Games.

“Yogasana is a viable career option now. Earlier, we didn’t know what we could do after learning yoga, but today, there are recognised competitions where it is a medal sport,” says Indu.

As the sport evolved, so did judging, says C V Jayanthy, a jury member. On their laptop screens, judges can see images of asanas submitted beforehand by competitors and punch in scores depending on the performance.

“Till four years ago, we had a very traditional scoring system – scores would be written on a slate or displayed using showcards. But with the addition of new events, the system has been revised. It is computerised so athletes get the points they deserve. In addition to the judges, there are three jury members (who act as referees). It is very scientific and accurate. Participants can register their protest, too, if required,” says Jayanthy.

Modern-day practitioners of yoga are not very different from other professional athletes, says Chhatisgarh coach Nurendra Kumhar, adding that they maintain diet charts and follow research-based warming-up and cooling-down routines. “They watch what they eat – there is restriction on sugar and ensure there’s more protein intake – cut down on body fat percentage, keep a tab on sleep patterns and have physios travelling with them. Ours is a sport with Asian Games and Olympic ambitions… The athletes are ready to embrace the future,” he says.

Satish Mohagaonkar, a veteran national yoga judge who is also the convenor of the technical committee at the National Games, talks about a vital administrative change that made life easier for officials like him. “Since the Department of Personnel and Training now recognises yogasana as a sport, any official or athlete who is a government servant can avail of special casual leaves for yoga-related events. All these years, I had to use my paid leave for yoga,” says Mohagaonkar, who has been doing yoga since the late 1970s.

Mohagaonkar believes that the awards and the incentives will draw more youngsters to the sport. “For example, the Maharashtra government gave prize money for winners of the previous National Games. We could not even dream of such perks earlier. There has been no better time to be a yogasana athlete.”

Sisters Purva Shivram Kinare and Prapti, qualified engineers, have won multiple medals at the National Games, since Yogasana was included at the 2023 edition in Gujarat. (Special arrangement)

Sisters Purva Shivram Kinare and Prapti, qualified engineers, have won multiple medals at the National Games, since Yogasana was included at the 2023 edition in Gujarat. (Special arrangement) A pair of Yogasana athletes compete in the Artistic Pair event at the 38th National Games in Almora. (Special arrangement)

A pair of Yogasana athletes compete in the Artistic Pair event at the 38th National Games in Almora. (Special arrangement) A teammate helps a Madhya Pradesh competitor with the make up before competition. (Special arrangement)

A teammate helps a Madhya Pradesh competitor with the make up before competition. (Special arrangement) Costumes matching with the theme of a performance, for example Shiv tandav, helps a competitor win points. (Special arrangement)

Costumes matching with the theme of a performance, for example Shiv tandav, helps a competitor win points. (Special arrangement) A modern yoga judge uses a laptop to punch in points on a specialised software that displays asanas. (Special arrangement)

A modern yoga judge uses a laptop to punch in points on a specialised software that displays asanas. (Special arrangement)