The Nation and the Goddess

Abanindranath Tagore’s iconic 1905 watercolour Bharat Mata is now on display at the Victoria Memorial Hall.

The Abanindranath Tagore painting was used extensively as an icon to incite nationalist feelings during the freedom struggle.

The Abanindranath Tagore painting was used extensively as an icon to incite nationalist feelings during the freedom struggle.

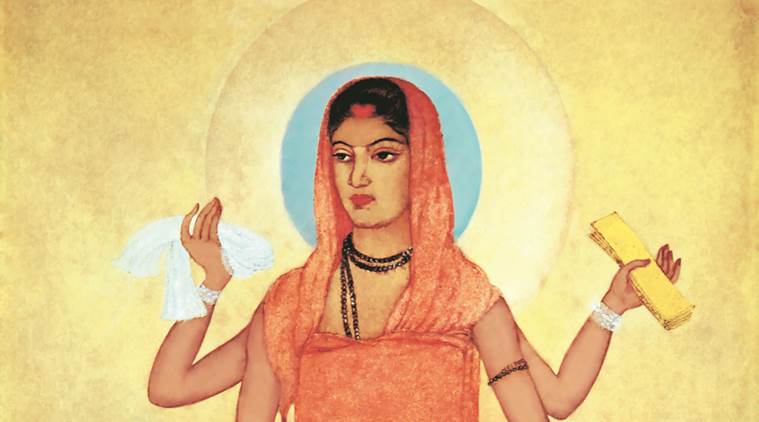

She is clad in a saffron-coloured saree, her head covered with the pallu. She is barefoot and her only adornments are a pair of shakha-pola, conch shell and coral bangles around her wrists — they are symbols of a married Bengali woman even today. She holds a book, sheaves of paddy, a piece of white cloth and a rudraksh rosary in her four hands. She has no weapons, neither is she wielding the tricolour, no elaborate mukut adorns her head and there are no fierce feline vahanas around her. Her face is marked with an expression of quiet contemplation, as if she is politely waiting for you to finish making your point before presenting her own interpretation of the issue at hand. Abanindranath Tagore’s iconic Bharat Mata, which is on display at the Victoria Memorial Hall (VMH) in Kolkata till June 9, looks more like a jogan than an awe-inspiring goddess.

The 1905 painting, which was used extensively as an icon to incite nationalist feelings in Indians during the freedom struggle, was a more “outward-looking” symbol than we are led to believe, says Sugata Bose, Member of Parliament from the Jadavpur constituency of West Bengal and a professor of history at the Harvard University. “Abanindranath Tagore wanted to make it an inclusive icon. Tagore was the first major exponent of swadeshi values in Indian art, which led to the development of modern Indian painting. Yet, he was a global citizen, who wanted to learn from other civilisations. You can see a clear influence of Japanese wash technology in the painting. In this style, the sides of the painting are blurred. He learnt this technique from Japanese painter Yokoyama Taikan. Taikan was sent to Kolkata by acclaimed art critic Okakura Kazua in 1903,” says Bose, who inaugurated the single-object exhibition at the Victoria Memorial on Monday.

The painting, which is the inspiration behind the contemporary depiction of the tricolour-wielding goddess, was initially not even meant to be called Bharat Mata, informs Bose. “Tagore, initially, wanted to call it Bongo Mata as a tribute to the quintessential Bengali woman. It was meant to be an empowering symbol of women. However, he eventually decided that the idea of Bharat Mata needed a strong visual representation,” says Bose. The painting and the concept of nationalism it exudes should be seen as an ideal, feels Bose. “The discourse of nationalism today has reduced to babble. The truth is that our nationalism movement has historically borrowed heavily from both Hindu and Muslim symbols. Mahatma Gandhi, in his journal Young India in 1920, suggested that we use ‘Bharat Mata ki jai’ as a slogan for the nationalism movement. But he also suggested that we use ‘Allah-o-akbar’ in that same journal. He also suggested ‘Hindu-Muslim ki jai’ as a slogan, but do we follow that suggestion?” asks Bose.

Jayanta Sengupta, curator and secretary of VMH, feels the painting will give the current generation a better idea about the “concept” of Bharat Mata. “We felt that it is a good time to show people this painting. There is a lot of interest in Bharat Mata now. As historians, it’s our duty to let people know about the genealogy of such symbols” says Sengupta. The painting itself, according to Sengupta, is a brilliant attempt to humanise the divine. “To me, the painting looks like an everywoman of Bengal. The painter clearly didn’t mean to intimidate the viewer here. It is meant to connect with the viewer, identify the subject as one of their own. Yet the halo around her head marks her as a divine entity. It is a recognition of divinity in all of us,” says Sengupta.

The symbol of Bharat Mata has been “misused and overtly politicised” over the years, feels Bose. “Today, the Bharat Mata that you see in calendars and posters is distinctly different from this depiction. That is symptomatic of the way people with vested interests use symbols to mislead others. Some have made the concept of Bharat Mata a communal thing. But Abanindranath Tagore never wanted it that way. This painting embodies the spirit of service that one has towards the nation. We seem to refuse to see that,” says Bose.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05