How a Whatsapp group helps refugees learn Rohingya language script, pass on to next generation

The Hanifi Rohingya script was included in a 2019 upgrade to the Unicode Standard, a global encoding system that changes written script into digital characters and numbers. Now, Rohingya can now email, text, and post on social media in their own language.

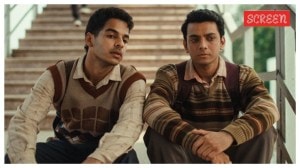

Mohammad Ismail teaching children the Rohingya script in a school he has built at the Rohingya camp in Faridabad. (Express Photo)

Mohammad Ismail teaching children the Rohingya script in a school he has built at the Rohingya camp in Faridabad. (Express Photo) It was in 2019 that Maulvi Mohammad Ismail, a Rohingya refugee living in a camp in Faridabad, learnt the letters of the Rohingya language.

The Rohingya language was predominantly oral till the 1980s before a script was developed by Mohammad Hanif. It is now called the Rohingya Hanafi script. Displaced from his home in Arakan, Myanmar, Ismail now teaches the language and the script to 35 children, from 6-13 years of age, living in this camp.

Faridabad’s Rohingya camp is located in the middle of a garbage dump yard. Barred from being employed, the 50-off families in the camp sort garbage to earn a meagre living. At the entrance of the camp, Ismail has built a small school, with woven bamboo walls and a cardboard roof. Twice a day – at 8 am and at 2 pm – Ismail lays down two mats in front of the board, and the children gather around him to learn the language.

“I left Myanmar in 2007 for Bangladesh to study. I was 16 years old then. It was very difficult to study in Myanmar. There were no schools or madrassas near our village. I had to travel from village to village to try and get education,’’said Ismail, who arrived at the Faridabad camp in 2015.

Ismail teaches Arabic and Rohingya languages to his students. Another teacher comes to the school to teach the children English, Hindi and Maths lessons.

“We no longer have a home. So, it becomes important for us to have a language to preserve our identity and pass it on to the next generation,’’said Ismail.

It took Ismail a month to learn the 28 letters of the Rohingya via a WhatsApp group. He has downloaded a few online textbooks and printed them – and these now serve as textbooks for the children.

The Hanifi Rohingya was included in a 2019 upgrade to the Unicode Standard, a global encoding system that changes written script into digital characters and numbers. Now, Rohingyas can now email, text, and post on social media in their own language.

It was after this encoding that the Rohingya Zubaan Online Academy, which primarily functions as a WhatsApp group, was set up by Rohingyas in Saudi Arabia and Bangladesh.

Like Ismail, Hafiz Abdullah learnt Rohingya letters through the Whatsapp group and is now teaching the script to around 150 children in three Rohingya camps in Mewat, Haryana.

“The academy also makes video lessons and sends them to the group. There are around 400 members in the group and the academy provides a certification at the end of a six-month course. Last year, 1,000 Rohingya children from all over the world were given certificates,’’said Abdullah.

“Teachers (in Myanmar) say they are banned from teaching the Rohingya language, history, and culture—and are even prohibited from using the word “Rohingya” in schools…In displacement, the Rohingya are further denied their language rights while facing additional challenges for accessing humanitarian aid…By not providing education in a child’s own language, especially one with strong ties to cultural identity, a government makes a clear and negative statement in regard to the value of that language and its people…Indeed, it is important to stress that discriminatory language policies are no accident; they are targeted state efforts to marginalise minority populations, deny political membership and erase cultural identities—meanwhile, often fueling ethnic tensions leading to conflict and mass atrocities,’’ the study said.

The Human Rights Review article says, “Most likely due to a history of continuous displacement and the dispersal of its speakers, Rohingya has remained primarily an oral language despite attempts to create a system of literacy. When communities of speakers are dispersed and unsettled, they are less able to produce a cohesive literature.’’