Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

A tale of two thanas: Maakhi, Unnao and Hiranagar, Kathua

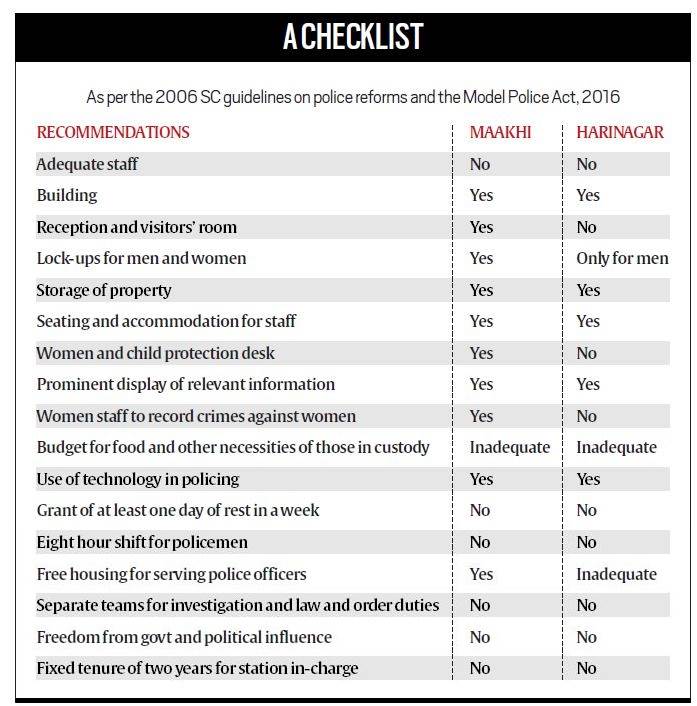

The road to justice in the Kathua and Unnao rape cases that convulsed the nation begins at two rural police stations where the First Information Reports were filed, where men and women work, against odds, to investigate evidence, interrogate witnesses — and build the case against the accused. Deeptiman Tiwari travels to Unnao and Arun Sharma to Kathua to find that the tale of these two thanas is also a story of neglect and despair. And an endless wait for police reforms.

The Maakhi police station (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

The Maakhi police station (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Unnao

On April 18, when a CBI team probing the Unnao rape case visited the Maakhi police station, they were delighted to see a CCTV camera. The officers asked station-in-charge Rajesh Singh to provide them with the footage. Singh instead came back with a file full of “communication” with the district police headquarters about getting the CCTV camera fixed — it hasn’t been running for four months now.

Had the camera been functioning, it would have provided crucial leads on the alleged assault on the victim’s father, leading to his death. The Maakhi police station in Unnao district of Uttar Pradesh has been under scrutiny since allegations of misconduct and favouritism were levelled against its men earlier this month in a case of rape of a 17-year-old, allegedly by BJP’s Bangarmau MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar. It has been alleged that the MLA raped the victim before subjecting her to gang rape but police at Maakhi refused to file an FIR.

When the victim’s family protested, the girl’s father was allegedly beaten up by the MLA’s brother Atul and his men. He was subsequently arrested by police on a complaint from Atul and taken to hospital, where the doctors reportedly declared him fit. A day later, he succumbed to his injuries in jail. Following the incident, six policemen from Maakhi were suspended and the case was transferred to the CBI.

Beyond this unflattering picture — of thana-level policemen as bumbling, corrupt personnel who give in to political pressure — the Unnao case and the one in Kathua, where the local police were accused of mishandling the case of rape and murder of an eight-year-old, highlight the deficits and disadvantages under which police stations in rural India function, and are yet expected to perform. Not surprisingly, every such sensitive case results in demands to shift the probe either to a specialised branch of the state police, such as the CID, or to the CBI.

On the face of it, Maakhi is unlike most other mofussil police stations that struggle for basic amenities. Located about 30 km from Kanpur, the police station in Maakhi is spread over three acres. Adjacent to the main building — which houses an office, an armoury, a lock-up and a computer room — is a garage. A few metres away are residences of the two muharrirs (book-keepers) and barracks for constables.

To the right of the main building is the residence of the station-in-charge, along with a mess where a meal costs Rs 30. Opposite the mess is a new building that houses the barracks for women constables. Opposite the main building is a newly constructed vistiors’ room. Behind it, a sprawling field, where the police station dumps seized vehicles.

Apart from a Mahindra Bolero for the station-in-charge and other staff, there are two PCR vans and two new motorbikes for patrolling. The men riding them are armed with palmtops, glitzy gadgets that they use to feed details from the spot and send back to the control room.

In the computer room are two computers — apart from one in the main office — and a printer. Two constables are constantly at work here, digitising all complaints, FIRs and action taken reports. There are two brand new generators too.

The front desk at the police station (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

The front desk at the police station (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

On paper, Thana Maakhi ticks all the boxes that the Model Police Act of 2016 demands of a police station in terms of infrastructure. Only, very few of these work.

The main office is a dimly lit 10×14-ft room with bundles of documents, case papers and registers spilling out of racks, rickety iron almirahs and steel trunks. On the walls are photographs of Mahatma Gandhi, Chandrashekhar Azad and, the latest addition, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath.

The armoury is stacked with World War-era .303 rifles, some with their butts partially broken and with magazines that have developed holes due to overuse.

The station has no facility to keep women. So when women are rescued and brought here, they are usually declared sick and sent to the nearest government hospital till an acquaintance or someone from the family comes to take them back.

Since there is no place for station-in-charge Inspector Rajesh Singh to sit, he has taken over the visitors’ room. Sitting there, he not only entertains guests, but also watches over about a dozen stray cattle that graze and rest on the police station premises.

The Bolero ventures out of the garage only occasionally since diesel is rationed —the station gets a quota of 200 litres a month for the four-wheelers. “It’s not enough. Our vans and jeep attend to complaints from 78 villages spread across over 250 sq km. But we manage somehow. Sometimes, in case of emergency, we ask villagers for vehicles,” says a policeman.

Around 5 pm on April 18, when a senior CBI officer enters the main office to check documents, a constable hurriedly switches on lights. “We manage with natural light for as long as we can. These bulbs run on solar power. We can’t afford to put them on during the day or else we will be in trouble at night. There is hardly any electricity for four to five hours a day,” he says.

There are generators, but the constable points out, “The diesel for the generators is rationed too — only 20 litres for the entire month. With that, we can only run these generators for an hour a day. Anyway, there hasn’t been any supply of fuel since December. We have sent out applications but money has not been sanctioned yet.”

The 10×12-ft rooms in the barracks mostly have broken doors, some supported with bricks and the others completely missing (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

The 10×12-ft rooms in the barracks mostly have broken doors, some supported with bricks and the others completely missing (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

The constables in the computer room usually work for a few hours in the morning, after which they sit idle. “With the inverter on, we can work only for a few hours. But when the battery goes down, we have to wait for power supply to resume,” says a constable in the computer room.

Inspector Singh has bigger worries. “I don’t have enough men,” he says.

The police station, which caters to a population of over 1.5 lakh, has a staff strength of 33, men and women who are deployed across four police chowkis and the main police station. Six sub-inspectors, two head constables, 17 male constables and seven women constables make up Singh’s team.

But the effective policing strength is far less. “All the women constables and five male constables handle complaints and other sundry duties at the police station. One constable is with me and two sub-inspectors are required here. That leaves 11 constables and four sub-inspectors to police 1.5 lakh people,” Singh says.

That number would put Maakhi’s police-population ratio at a mere 11 policemen per one lakh population. The UN mandated police-population ratio is 222.

“The police station is running thanks to recruits under training (18 of them) and home guards (20). The recruitment process is very slow,” says Circle Officer Vivek Ranjan Rai.

But for one vacancy, the strength at the police station almost matches the number sanctioned for it. “Why wouldn’t it? The sanctioned strength has remained the same since the day this police station came into being in 1987,” says a policeman, who has spent “several years” at Maakhi.

Constable Naresh has just come off a 12-hour night duty but has to rush to Unnao for an administrative matter. The Model Police Act says duty hours should not stretch beyond eight hours.

“Forget weekly offs, most of the time we do not even get enough sleep,” says a constable. And when they do sleep, they do so lightly in the dilapidated barracks. The doors of the 10×12-ft rooms are mostly broken, some supported with bricks and the others completely missing. “Dogs and cats walk in and out,” says a constable.

In the midst of all this, the station deals with complaints ranging from murder to property disputes, with an average of 400-450 cases a year. “Around 20 per cent of these are rape cases, including those arising out of elopements. Those make for the highest number of cases at the police station,” says Arvind Tripathi, the head book-keeper, adding that chargesheets hadn’t been filed in 20 per cent of the cases with the station.

Sub-Inspector Prem Narayan (left) and book-keeper H Khan at the main office room, a dimly lit 10×14-ft structure (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Sub-Inspector Prem Narayan (left) and book-keeper H Khan at the main office room, a dimly lit 10×14-ft structure (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Then there are “out-of-complaint-book” settlements that police have to engage in — from domestic squabbles to minor cases of assault. “Only this morning I spent an hour trying to pacify a father who accused his daughter of having sold the wheat they harvested and not giving him his share,” says sub-inspector Prem Narayan.

A tight policing budget means constables have to sometimes spend from their own pockets. “We get two litres of petrol a day for our bikes. Last month we had to contribute for the gas cylinder in the mess,” says a constable.

When accidents occur in areas under the station’s jurisdiction, the injured have to be carried in vehicles borrowed from villagers. On Wednesday, policemen requested a set of suspects to use their own bikes to reach the police station for questioning.

With “important” people, including local politicians, streaming into the police station through the day, Singh adds, “There is no budget to entertain guests. So we have to pay from our own pockets.”

Says a constable, “We dread finding an unidentified and unclaimed dead body in our area. The government gives only

Rs 1,000 for cremation, but it costs at least Rs 2,500. The panch witnesses take Rs 500 to sign the panchnama. Then, we have to arrange for vehicles to ferry the body, pay for wood…” That’s a tough ask, considering a constable’s salary in Uttar Pradesh ranges from Rs 5,700 to Rs 20,200.

Questions about political pressure are mostly met with a wink and a nod. “How do you withstand pressure? An inspector from a nearby police station was suspended after he leaked an audio of the local MLA threatening him. What do you think is the message that goes out?” asks a policeman.

As night falls, the solar bulbs light up. Trivedi, the head book-keeper, and the other policemen get busy swatting mosquitoes.

***

The Hiranagar police station was set up in the 1930s (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

The Hiranagar police station was set up in the 1930s (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

Kathua

I have been sitting on his chair since 8 am,” says Anchal Singh, 54, looking up from the pile of papers on his table at the Hiranagar police station in Jammu’s Kathua district.

For the last 11 hours, says Singh, he has been clearing dak (official letters), attending to phone calls and visitors, relaying messages from local people and senior officers to constables on the field, besides recording every entry and exit at the police station. “Everything has to be noted down in the register here. So work or no work, I cannot leave this chair,’’ says Singh, who, as munshi of the Hiranagar police station, is the man responsible for writing FIRs and maintaining records.

Set up in the 1930s, the police station is now in the midst of a raging row over an alleged botch-up in a case of gang rape and murder of an eight-year-old girl in a village that falls under its jurisdiction.

The case, that has now come to be known as the Kathua gang rape case, has so far led to the suspension of station house officer Suresh Gautam and the arrest of four policemen, besides a juvenile and three other accused, among them retired revenue official Sanji Ram, who is the main accused, and his son Vishal.

After the suspension and arrests, the police station has only 25 constables and five officers. Of these 30 policemen, four are investigating officers (IOs) and two computer operators who are tasked with feeding FIRs and roznamcha (daily diary) in the station’s four computers. At least one constable is on sentry duty at the main entrance at any given time, apart from the munshi and “chotta munshi”. That leaves the police station with only 21 constables and officers to police 1.25 lakh people in the 92 villages under its jurisdiction, a number that’s well short of the sanctioned strength of 49.

This skeletal force also has to man the nearly 7-km stretch of the busy Jammu-Pathankot national highway, which is 1 km from the station and which witnesses frequent movement of VIPs, besides road accidents and frequent demonstrations.

Nearly half the villages under its jurisdiction lie metres away from the 9-km-long stretch of the International Border with Pakistan, with known infiltration routes passing through the area. The police station has three police posts and a check post along the border, each with over a dozen policemen and led by a sub-inspector or assistant sub-inspector.

Munshi Anchal Singh (wearing a cap) and S-I Rattan Sharma at work (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

Munshi Anchal Singh (wearing a cap) and S-I Rattan Sharma at work (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

In 2013, militants had attacked the Hiranagar police station and killed six people, including four policemen. Ever since, security at the border posts has been tightened with all its men holding nakas throughout the night along infiltration routes. “They can’t be spared for routine duties. So in case of a crime in these border villages, we may at the most ask constables to bring the accused to the police station,” says SHO Tilak Raj Bhardwaj, who has just come in from Kootah Morh along the national highway, where a group of women under the banner of the Hindu Ekta Manch have been holding a fast, demanding a CBI inquiry into the Kathua case.

Bhardwaj, who came from Kathua to take over as SHO on January 20, after the then SHO was shunted out, is waiting to be relieved of his post — he was recently promoted as Deputy SP to India Reserve Police’s 24 Battalion.

He says that with the police station perpetually short of men, they have engaged Special Police Officers (SPOs) to deal with law and order duties, VIP movements, crime and militancy. The SPOs, who are engaged from time to time on a meagre monthly remuneration, which was recently revised to Rs 6,000, are not regular policemen. Two SPOs from this station are among those arrested in the rape case.

“Despite shortage of staff and inadequate infrastructure, we try our best to attend to all those who come to the police station,’’ the SHO says, refusing to wade into the recent controversy and the string of accusations against how policemen at the Hiranagar station handled the case — that the police were indifferent to the father’s complaint about the girl being missing, and that they washed the blood- and mud-soaked clothes of the girl before sending them to the forensic laboratory.

Sitting in one of the four rooms on the ground floor of the two-storeyed building, Bhardwaj instead sticks to statistics — since 2011, he says, the police station has registered 1,128 cases, of which only 102, including 49 registered this year, are pending disposal.

With the barrack taken over by CRPF, two to three constables share a room in the family quarters (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

With the barrack taken over by CRPF, two to three constables share a room in the family quarters (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

Besides the SHO’s room, there is one for munshi Anchal Singh, another for the malkhana (where all evidence and key seizures related to cases are kept) and the armoury, besides two small lock-ups, on the ground floor. However, for want of space in the malkhana, police use one of the lock-ups as a storeroom. With no reception area, visitors usually wait for their turn on the ground outside.

On the first floor is a room shared by 18 SPOs and another with four computers. A small barrack on the same floor is occupied by nearly 15 personnel of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), which has been permanently stationed here since the 2013 attack. With the arrival of the CRPF, the 30 policemen were shifted out of this barrack to the family quarters on the campus, with two to three of them sharing each room.

All the personnel eat from the mess on the campus. Though the government pays Rs 1,000 a month as ration money to each of them, one of the constables says the money is never enough. “We end up paying Rs 1,200-1,500 every month from our pocket. We also share our food with those in the lock-ups,” he says.

Munshi Anchal Singh says there is no provision to keep women accused at the police station at night. The four women personnel, including an SPO, have taken rooms on rent outside the police station. In case a woman complainant turns up at night, one of the women personnel is called to the police station, he adds.

The police station has two vehicles, a Tata Sumo for the SHO and a TATA 407. A police officer says that for the Sumo, which is used by the SHO, the police station gets 150 litres of diesel a month, while the other vehicle, meant for rushing police deployments or taking accused to the court, gets 100 litres of fuel. “The fuel is never enough because we have to cover such a large area, but we manage… we keep requesting senior officers to issue extra fuel,” he says.

Sitting in the room adjacent the munshi’s, constable Mohammad Hussain, 34, talks about home and family — how his wife and three daughters, the eldest 4 and the youngest a year old, live in Chadwal, a mere 12 km away. Yet, he says, the last time he went home on a day’s leave was on April 8 this year to attend a relative’s wedding.

Of the two lock-ups, one is used as a storeroom (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

Of the two lock-ups, one is used as a storeroom (Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

Hussain has been in service for the last seven years, of which he has been posted at Hiranagar for 18 months. He shares a room with two other constables in the family quarters of the police station.

Sub-inspector Rattan Sharma soon joins in. “We have 15 days of casual leave and a month’s earned leave, but none of us gets to avail them. Because of our uncertain duty hours, the state government gives us an additional two-and-a-half days’ salary at the end of every month,” says Sharma, who joined the J&K

Police as a constable in 1979. “But is it enough to compensate us for all the time we spend away from our families?” asks another official.

SHO Bhardwaj agrees. Ever since he took charge here, he has gone home to Akhnoor, around 90 km away, only for a day, “that too for a medical check-up”. The last time he took a “long leave” of 10 days, he says, was when his mother died in October 2015 and then in December same year when his father died.

Bhardwaj soon gets a message about a VIP convoy passing through Hiranagar town and rushes there. A little after the convoy has passed, he has to attend to an SOS call from the team posted at the Kathua victim’s village. He returns to the police station only at 8 pm. Just then, his phone rings again – the condition of a woman protester at Kootah Morh has deteriorated and she needs to be taken to hospital.

The wishlist

(Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

(Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)

Maakhi Police station:

More staff: “No amount of gadgets or amenities will be of any use, if I don’t have enough men. I have 12 constables to police 1.5 lakh people. How do I focus on anything but just managing law and order?” says station-in-charge Rajesh Singh

A crane: “Most law and order situations develop when an accident happens, the road is not cleared quickly and people begin gathering. We have nothing to manage that as of now,” he says

An ambulance: With no ambulance to carry accident victims, policemen usually request passersby to carry the dead and injured to hospital

Training in law for Sub-Inspectors: “A law degree must be made mandatory for S-Is before they join the force. It would help a great deal in probing cases,” says Singh

Fuel: “We can still function without power, but how will all the digitisation work? Neither the generators, nor the vehicles will run without fuel”

(Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

(Express Photo by Ankur Sethi)

Hiranagar police station:

More staff: SHO Tilak Raj Bhardwaj says he needs more hands. The police station has 21 constables and officers — well short of the sanctioned strength of 49 — to police the 92 villages in its jurisdiction

Better accommodation: With the CRPF taking over the barrack on the first floor, the 30 policemen now stay in the family quarters, usually two to three of them sharing a room

Investigation tools: The police station does not have a basic investigation kit, including needles, thread and gloves

Separate rooms, accommodation for women personnel: The four women personnel have taken rooms on rent outside the police station. In case a woman complainant turns up at night, one of the women personnel is called to the police station

Better mobility and communication: The police station has two vehicles, but with diesel rationed, policemen say they have to keep requesting senior officers to sanction extra fuel