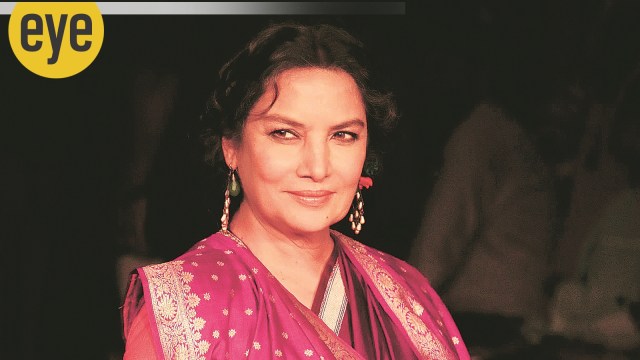

Shabana Azmi looks back at her 50 years: ‘Change in cinema has to come from the mainstream. Otherwise, you are preaching to the converted’

Five decades after Shabana Azmi made her powerful debut with Ankur, the actor charts her extraordinary journey.

Shabana Azmi looks back on her five-decade creative journey, influences and choices. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)

Shabana Azmi looks back on her five-decade creative journey, influences and choices. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)After catching attention with her National Award-winning big screen debut as Lakshmi, a lower caste and morally ambiguous villager in Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (1974), Shabana Azmi has etched out a cinematic journey with riveting performances. With the rare feat of winning five National Awards for Best Actress — for Ankur, Arth (1983), Khandhar (1984), Paar (1985) and Godmother (1999) — and a masterful turn in both mainstream and arthouse movies, Azmi is arguably one of India’s most gifted actresses.

Her oeuvre ranges from embodying a lonely wife of an aristocrat in Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khilari (1977); an over-the-top brothel owner in Mandi (1983); submissive Radha, who walks out of her stifling marriage to be united with her sister-in-law, in Fire (1996); a cunning woman pretending to be a witch in Makdee (2002); to portraying young-at-heart Jamini Chatterjee in Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani (2023), and Admiral Margaret Parangosky in the American sci-fi series Halo (2022–2024).

The Padma Bhushan recipient has also been a fearless activist, raising her voice against communalism, taking a stand for the welfare of slum dwellers and extending her support to remove the stigma attached with AIDS. Clearly, Azmi’s choices in life have been influenced by her upbringing. Being the daughter of actor Shaukat Azmi and leftist poet Kaifi Azmi, her family lived in Red Flag Hall, a communist commune, in Mumbai till she was nine. Later, their home at Janki Kutir in suburban Mumbai would be frequented by prominent writers and artists of that time, including Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Josh Malihabadi, Firaq Gorakhpuri and Begum Akhtar.

Seated in her sea-facing living room in Mumbai, Azmi, 73, looks back on her five-decade creative journey, influences and choices. Excerpts:

A still from Ankur.

A still from Ankur.

What are the memories from the sets of Ankur that you still cherish?

At that time, I was fresh out of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune. The mahaul (atmosphere) was more like a theatre group working together. I was this typical St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, student and had never lived in a village before. Shyam Benegal asked me to wear a sari and walk around the village to get the gait right. When he realised that I couldn’t sit on my haunches, he asked me to sit in a corner and eat. A couple of days later, a few college students visited the set and asked me: “Heroine kidhar hai (where is the heroine?)”. I told them she was on leave. When they asked who I was, I replied: “Main aayaa hoon (I am a help)”. After witnessing this, Shyam said: “Now that you have convinced them you are a help, you can eat with us at the table”.

Ankur received both critical and commercial success when it was released. Did that take you by surprise?

When we were making the film, people tried to dissuade me, saying that ‘in your first film, you are playing an adulteress and stealing rice’. I loved the grey shades in Lakshmi’s character. All along, I knew something exciting was going on. Once Ankur released, it was like a whirlwind. It was selected for the Berlin International Film Festival, 1974. It gave me my first National Award for Best Actress. Ankur’s commercial success paved the way for other arthouse films. Had I not started my career with Ankur, my career would have been on an entirely different trajectory.

From the beginning of your career, you kept moving between mainstream and arthouse cinema with ease.

There was no game plan. In retrospect, I think that was my thought process. I never considered myself a commercial heroine. But these roles fell into my lap so to speak. I hoped the mainstream movies would help the art house movies that I was doing. I was adding to the commercial value of these films. Mainstream movies paid me better.

A sill from Masoom.

A sill from Masoom.

In 1983, three important yet different movies — Avtaar, Mandi and Masoom — released.

I knew Avtaar would be a success because what it was saying was so crucial. It touched a chord. In those days, if you just had grey hair and no make-up, you could pass off as an elderly person.

Before shooting Mandi, I visited three brothels — in Mumbai, Delhi and Hyderabad. When I went to Hyderabad with Shyam, we met this woman wearing a simple green nylon sari. Then, she started dancing to the song Dil mein tujhe bithake, which sounds almost devotional, from my film Fakira (1976). The dance was so vulgar that it took me by shock. After this visit, I was convinced that a brothel owner can be a young woman.

Is your character of Jamini in last year’s Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani a tribute to Khandhar?

Not at all. My character in Rocky… is so different. In spite of being sensitive, she is quite outgoing as compared to Jamini of Khandhar. When I was doing Rocky… what I wondered the most is how they (she and Dharmendra’s character) were going to burst into this Hindi song: Abhi na jao chhod kar (from Hum Dono, 1961). Karan Johar was convinced that it would work. He was right. I’m grateful to Manish Malhotra (for the costume). A Bengali woman, for me, is one in bindi and cotton saris. In my first scene, I was in a silk sari, with open hair and making maccher jhol (fish curry). I told Karan no one with open hair makes fish curry. He said: ‘Karan Johar does that and just relax’. That worked. So many youngsters, who are not familiar with my earlier work, really loved her.

You kissing Dharmendra became talk of the town.

It was just a peck. Not for a second was Dharamji or I conscious about it. I find it very silly that it became such a major talking point.

It is evident that a number of Bengali directors loved to work with you.

I worked in several Hindi films made by Bengali directors including Ray, Mrinal Sen, Tapan Sinha, Aparna Sen and Goutam Ghosh. It started with Ray. I spent three precious days on the sets of Shatranj Ke Khilari. After that, whenever I asked Ray to cast me, his response used to be: ‘I don’t believe that you will be a good Bengali’. But he used to ring me up after watching my movies such as Paar and Khandhar to share his observations about my performance.

A still from Khandhar.

A still from Khandhar.

The next major Bengali director you worked with was Mrinal Sen.

I used to badger Mrinal da to cast me. When he finally did cast me in Khandhar, it was as if that role was meant for me. He told me the story in 20 minutes. I wondered how he was going to make it effective on screen. When I see the movie, even now, I am amazed.

Even though he was garrulous, he was also a shy person. He identified with Jamini (who leads a lonely life in a dilapidated ancestral home). Working with him for Genesis (1986) was wonderful. It was ahead of its time. It was shown at the Cannes Film Festival. I was meant to attend it. Instead, I decided to join the hunger strike of slum dwellers under Nivara Hakk (to support their housing rights).

You spent your childhood in a communist commune. How did that impact you?

Because of my parents, I have always believed that art should be used as an instrument of change. Change is a long process. But any form of art — be it music, literature, painting film — can create a climate of sensitivity which enables change to take place. I was greatly influenced by the artistically rich environment I grew up in. Also, by my father’s writing and the kind of roles my mother did.

I remember my mother’s plays clearly. When she used to work on her new character, she would dress up like the character, change her voice and gait. This is something I have followed till today.

How was the experience of playing your mother’s role in the remake of Umrao Jaan (2006)?

My mother helped in buying the fabric for the costume but did not explain her process. I decided I should not be overawed by it. A fan, who had obviously watched all my movies and admired my work, wrote me a letter: ‘You are so disappointing in the role that your mother had essayed and made it memorable’. I didn’t have his address. Otherwise, I would have definitely written to him.

Even though we saw many powerful women characters in parallel cinema, why did they not create a lasting impact?

If you want change in cinema, it has to come from mainstream cinema. Otherwise, you are preaching to those already converted.

When you signed Fire, did you know that it would be a landmark?

Initially, I had my reservations about it since I was working in the slums and there was a lot of resistance from the men there. Javed (Akhtar, screenwriter-lyricist and Azmi’s husband) said if you believe that the film is not exploitative and you would enjoy doing it, then do it.

A still from Fire.

A still from Fire.

Makdee reimagined you as a witch.

Many young people today come to me and say that the first movie of mine they watched was Makdee and they were so scared. So, obviously it had an impact. I knew the make-up had to be right because there was no great emotion I had to bring to the role. Arjun Bhasin, who designed the costumes, gave me 12-inch heels. Almost like wearing stilts. Vishal Bhardwaj (director and writer) and I tried multiple looks before settling on this one.

There is a lot of discussion today around method acting. What’s your take?

At FTII, I learnt acting the Konstantin Stanislavski way. It has helped me to build a world, a backstory and use my emotions for reaching an emotion. In Ankur, when I had to scream at Anant Nag at the end, I did not know how to reach that high. I was feeling a little shy to let go. I went to the fields and recalled playing a Black woman in a play written by Imtiaz Khan, Amjad Khan’s brother. In its last scene, my character was screaming at God and wondering if God was only for the Whites. I went back and pulled out all stops when the filming started.

A still from Mandi.

A still from Mandi.

Which is your favourite among the characters you have played?

I do like Jamini in Khandhar. Then, there’s Amrita from the play Tumhari Amrita.

Your Holi and Eid feasts are famous.

While growing up, we celebrated all festivals. When we moved to Janki Kutir from Red Flag Hall, Abba was keen that we continue celebrating them. For me, this is part of my composite culture. My brother (Baba Azmi) and I greatly enjoy these occasions.

You have a girl gang, with whom you travel together.

They are my friends from school and college. My sister-in-law Tanvi Azmi is part of it too. Every year, we manage to do one trip abroad and in India. Javed has given us the nickname ‘Laal Lagaam’. We are much older now, conscious of our knees and joints. But these trips are like fresh air.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05