Remembering poet Surjit Patar, whose writing pierced one’s conscience

Padma Shri-winning Punjabi poet Surjit Patar, who passed away last week, will be remembered for his metaphors that spoke a thousand words and verse that took a nosedive into Punjab's pain and passions with equal felicity

Surjit Patar

Surjit PatarWhen radical Punjabi poet Avtar Singh Sandhu, better known as Pash, was incarcerated for his Naxalite links in the 1970s after the publication of Loh Katha (Iron Tale), a fiery and provocative book that riled up the establishment, he wrote a letter to his friend and poet Surjit Patar, asking him to never be consumed by praise. “You are a sensitive poet but I am not happy with you writing ghazals,” he wrote and added. “Popularity is a noose around your neck. Don’t let it sway you.”

The two, in their 20s then, would often discuss ideas about identity, and belonging, the pain of the Partition and the ideology and cadence in the writings of Chilean poet and politician Pablo Neruda. Patar’s affection for Begum Akhtar’s ghazals had led him to delving in the form. He continued, despite Pash’s displeasure with the matter.

Pash’s direct attack on the Khalistani ideology through his writings, earned him the ire of Punjab’s militants in the 1980s; he was shot dead in 1988.

Years later, Patar wrote:

Asi hun mud nahi sakde

Asi hun mud gaye phir tan samjho mud gaya itihaas pichhe

Jit gayi haume te nafrat di siyaasat,

Jit gaye kaatil manukhta de

(We cannot return now. If we do, it would mean that history has gone backwards, the arrogance of hatred and politics has won. If we return, it’d mean that the killers of humanity have won).

In 2020-21, these lines became succour for the protesting farmers from Punjab who’d recite them during their speeches. When the protests were met with brute force from the Central government, Patar returned his Padma Shri, awarded to him in 2012 for his unfeigned writing, for being the people’s poet, with generations appreciating his work. This was not the only award Patar returned. In 2015, when journalist Gauri Lankesh was killed outside her home followed by scholar MM Kalburgi, and author and politician Govind Pansare, Patar was one of the first few to return his coveted Sahitya Akademi Award. This was right to dissent at its best. Pash would have approved.

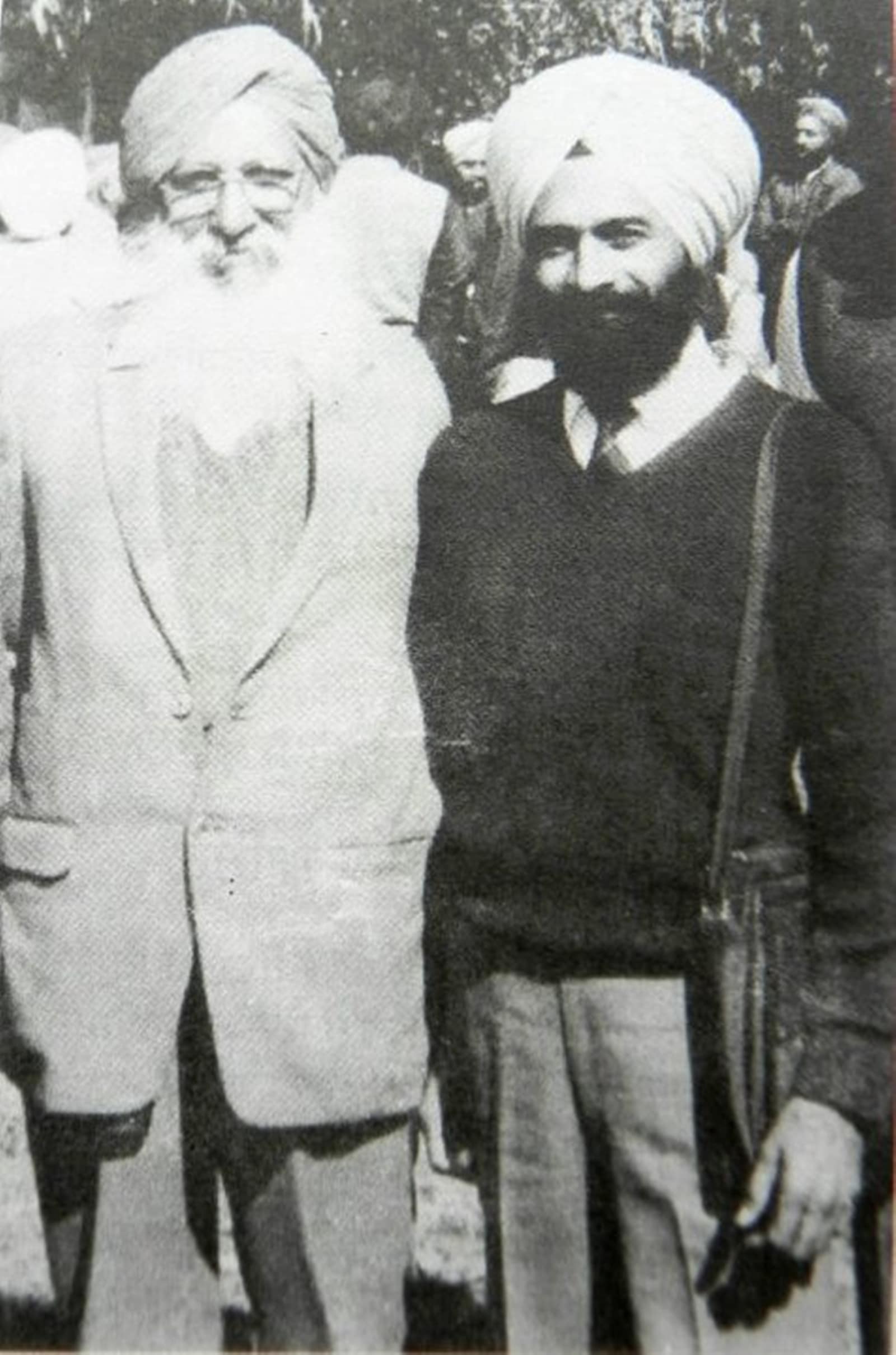

Surjit Patar with Harbhajan Singh

Surjit Patar with Harbhajan Singh

Patar’s gentle yet stark metaphors delving into socio-political issues, graciously allowed one to enter the world he saw. He passed away on May 11 due to cardiac arrest in his sleep. He was 79. “Saadi ma boli da veda soona ho gaya (Our mother tongue’s home has been deserted,” said a tearful Bhagwant Maan, Chief Minister, Punjab, who also became a pallbearer for a poet he read and often quoted in his speeches. It isn’t usual for politicians to weep for artistes. But then Patar’s words came and sat next to you and spoke to your heart, even of the mighty decision-makers.

The evening before he passed, Patar was at Punjabi Sahitya Sabha in Barnala, where he read his poem, Jaga diyan mombattiyan (Candles of the World):

Hanera na soche ki chaanan mar gayya hai

Baal jyotaan zindagi de maan mattiyan

Uth jaga de mombattiyaan

(Darkness should not believe that the moon is scared/ Light up the flame to honour life/ Get up and light the candles)

Born in Pattar Kalan in Punjab’s Jalandhar (his surname was an inheritance from his village), the poet’s affection for music came from listening to his father sing Gurmat Sangeet. The longing, however, was for the embrace of his father, who left home to work in Kenya. Dil hi udaas hai ji, baaki sasb khair hai (It is the heart that’s desolate, Rest, everything is fine), he wrote about the incident relating it to numerous stories from Punjab where men migrated to provide for their families. It was also probably why Patar’s writing was often rooted in the motif of darakht (tree), various kinds, their life and times, often comparing himself to one. Filmmaker and writer Gulzar told Patar once, “Darakht features often in your poetry, while it’s the moon in mine.”

Patar finished his Masters in Literature from Punjabi University in Patiala followed by a doctorate in ‘Transformation of Folklore in Guru Nanak Vani from Amritsar’s Guru Nanak Dev University. While he wanted to be a singer, it’s the rich literature of Punjab and writings of pioneering poets such as Mohan Singh and Harbhajan Singh followed by association with Shiv Kumar Batalvi and Pash which turned him towards poetry about the land he inhabited, it’s culture, its issues, the pain, its grief, especially during the dark period of the 80s, when he invoked Punjab’s distinctive essence, its culture, its linguistic identity, a shared past, thereby subverting any larger concepts of division. As Punjab burnt, he wrote,

Laggi nazar Punjab nu, edhi nazar utaaro

Le ke mirchaan kaurriyan, ehde sir ton waaro

Waar ke, agg de vich saarro

Laggi nazar Punjab nu, edhi nazar utaaro

(Punjab is under the influence of evil eye, Ward off the effects of the evil eye/ Take the chillies and conch shells, encircle around its head/ After encircling burn them in the fire/ Punjab is under the influence of evil eye, Ward off the effects of the evil eye.

A professor at Punjab Agricultural University in Ludhiana, around the same time, Patar also harked back to Amrita Pritam’s famed Ajj akhaan Waris Shah nu (Today, I invoke Waris Shah), and penned,

Odo Waris Shah nu vandeya si, Hun Shiv Kumar di baari hai

O zakham twanu bhul vi gaye, Naveya di jo pher tayyari hai

(In 1947 you divided Waris Shah, now it’s Shiv Kumar’s (Batalvi’s) turn/ Have you forgotten the wounds of the past that you are ready to inflict new ones?).

Taking off from Pritam’s intense piece, Patar’s sarcasm was trying to appeal to the collective consciousness of the people of Punjab. His notable poetry included Hanere vich sulagdi varnmala and Lafzan di dargah among others.

Patar’s passing last week is a reminder of not only his layered and river-like poetry, with simple metaphors which represented the rich literature of Punjab in its graceful cadence and contributed significantly to academic discourse but also an affirmation of the lacuna between the real Punjabi language and the popular, depleted ideas that represent it as an unthinking and unintelligent space.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05