Iranian women are ready to stand up for their rights: Activist Masih Alinejad

Activist Masih Alinejad on growing up in Iran, inspiring social media resistance and why her countrywomen are letting the hijab slide.

“My principle is simple — I am for women’s right to choose”. – Masih Alinejad

“My principle is simple — I am for women’s right to choose”. – Masih Alinejad

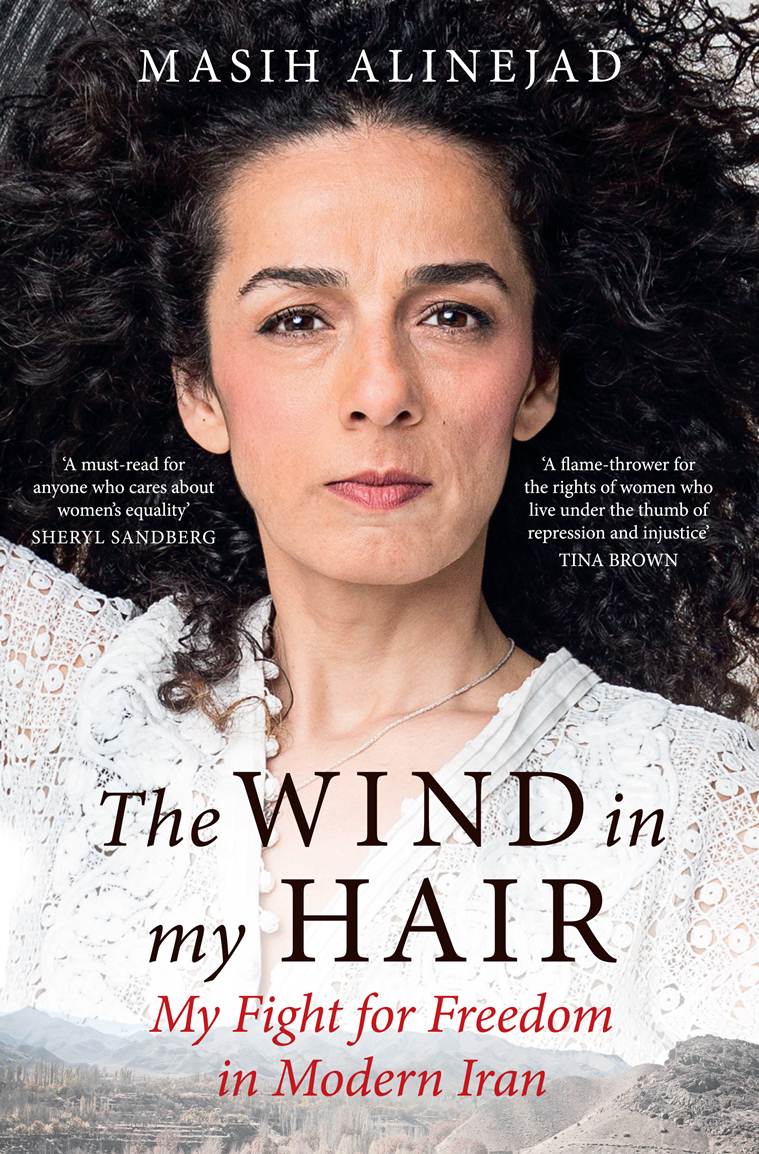

Women in Iran break the law every single day just by being themselves. “Though we have more rights than our sisters in Saudi Arabia, we suffer from discrimination just the same…. From employment laws that discriminate against women, to divorce laws that give custody of children to men, to the fact that women cannot run for the top office in the country, or qualify to be judges, women are curtailed,” writes Masih Alinejad, 41, in a new memoir, her first book in English, The Wind In My Hair: My Fight for Freedom in Modern Iran (Hachette), out in India earlier this month. She has written four books in Persian before this.

Alinejad writes of the unwritten rule that a girl must wear the hijab, from the age of seven, if she wants an education, a job, a husband, or even be spoken to by cabbies, cops and ministers. The Iranian journalist-activist, who has “too much hair” and a “loud voice”, was only a two-year-old in the village of Ghomikola in northern Iran, when the Islamic Revolution saw Ayatollah Khomeini overthrow Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi’s regime. From a young age, Masoumeh, as she was called then, stood up to her revolutionary father (a member of Basij, the Iranian paramilitary force) and the state in her subversive ways. Much later, as an exile living in New York (she left Iran in 2009 and studied in the UK), she stirred up a storm by letting her black hair free. The image became the face of her 2014 online campaign, “My Stealthy Freedom”, inspiring Iranian women to rail against compulsory hijab. That led to the campaign, “White Wednesdays”, where women, dressed in white, take to the street, taking off their headscarves and waving it, even in the face of abuse or arrest.

These have spawned #GirlsofRevolutionStreet protest and #MyCameraIsMyWeapon campaign, where women film and post online their altercations with the morality police. Alinejad’s Facebook and Instagram accounts, with over a million followers each, bear testimony to that. Excerpts from an email interview:

Unlike older women in your family and village, you hadn’t experienced the freedom of the Shah regime. Yet, you chose to fight. Why?

When I was a child, I would be incensed that my brother Ali, who was only two years older than me, could run around in the streets and go swimming in the nearby stream while I had to stay indoors. I hated that he could walk around in a pair of shorts in summer but I had to be covered up from head to toe. I kept noticing how boys, and later men, enjoyed privileges denied to girls and women. I became politically active because I wanted a fairer society.

By the way, I only saw pictures of my mother in a skirt, worn over a pair of trousers, when I was in my 30s. They had kept it hidden from me!

In an interview when you were asked about the colour of your mother’s hair, you said you didn’t remember. Do you know now?

I haven’t seen her hair since I was a teenager. It was light brown, unlike mine which is dark as coal. It must be grey now. I can only imagine her hair colour.

She taught you to ‘open your eyes wide and stare down darkness’ and to ‘never let them lock you out’.

As a young girl, you look to your mother for strength, inspiration and love. My mother is tiny. But she is very tough. When she decides to stand up for her rights, she does not back down. There have been a number of times when I have faced major setbacks, for example, my divorce, which in a conservative family was taboo. But my mother’s toughness helped me. She wouldn’t call herself a feminist but she showed me how to be strong. Even though we don’t agree on politics, I admire her sacrifices and her toughness.

The book cover of The Wind in my Hair.

The book cover of The Wind in my Hair.

You write about how your hair was like a ‘hostage in the hands of the Iranian regime’. But you didn’t approve of France’s burkini ban or US’s hijab ban.

I’m not against the hijab. I am against compulsion. In the US, I have protested against (Donald) Trump’s ban on travellers from Islamic countries and against his treatment of women. In Europe, I protested against France’s burkini ban and spoke at the European Parliament about it.

My principle is simple — I am for women’s right to choose. You cannot discriminate on the basis of gender, religion, race or nationality. I cannot fight every battle, every injustice. I limit myself to Iran and the Middle East when it comes to the issue of women and the hijab. I defend the right of a Muslim woman who wants to wear hijab and the right of someone who doesn’t want to. In the West, there are political parties that oppose Trump and the burkini ban and you could fight to change the law. But in Iran, there are no free elections and no free press and so it’s more difficult to bring about change when the regime effectively blocks its opponents from having any say.

The movement to let one’s hair down has spilled from the kitchen to social media to the streets. How many Iranian women have been arrested for participating in ‘My Stealthy Freedom’ and ‘White Wednesdays’?

The last data that we have is that 3.6 million women were arrested or warned or cautioned for inappropriate hijab, meaning their hijab was not completely covering all of their head or body. But that data is from 2016. Another data point is that in the same year, 40,000 cars were impounded because the women driver had inappropriate hijab, meaning her headscarf was loose when she was behind the wheel. The government has stopped releasing such data to avoid public embarrassment by our campaign.

More recently, 29 White Wednesday activists were arrested in one day and their situation is still unknown. One activist, Shaparak Shajarizadeh, received a 20-year sentence. This shows how worried the Islamic Republic has become.

I feel tormented and pained about each of these arrests. I hire lawyers and do my utmost to secure their release. And yet, these women are not robots controlled by me; they are ordinary people who are fed up with the oppressive laws of the Islamic Republic. We have to respect and admire them. To live in the Islamic Republic, you have to break the law to live a normal life.

Is mobilising women easier from outside the country?

In May 2009, I was in Iran covering the presidential elections. The authorities gave me a choice – leave Iran or face jail. At that time, I worked for the daily newspaper Etemad Melli, owned by presidential candidate Mehdi Karroubi. He told me he couldn’t protect me and I better leave and return after the elections. Karroubi and Mir-Hossein Mousavi, the other challenger to (Mahmoud) Ahmadinejad, are still under house arrest.

Had I stayed, I would have been arrested and jailed for a few years. I would not be starting a campaign against compulsory hijab. Because I am outside the reach of the security forces, I can do a great deal that I could not whilst I was inside Iran.

Singing, dancing and watching men play at a stadium are a no-no for Iranian women. But this year’s Fifa football World Cup match in Tehran let women in (an exception to the norm). Are things changing?

The stories are positive because women, and men, have struggled to win (certain) rights. Before the revolution, women attended soccer matches in stadiums and there were never any problems. Why should we jump for joy for a right that we had four decades ago? But let me say that the women were allowed to watch a telecast of the game beamed in from Russia after many hours of protesting. It turned into a publicity disaster just as Iran was trying to show how reasonable it is compared to Trump.

There is outside pressure on Iran. No doubt the new US administration is focusing on Iran in a way that the Obama administration did not. This forces the Islamic Republic to make concessions. The alternative explanation is that women are ready to confront the morality police and stand up for their rights. The internal pressures of the society are bringing about changes. The regime cannot hold the line on all issues and has to make concessions. The stadium was one example.

Why did you give up your Islamic name Masoumeh for the more Christian Masih?

My friends had already shortened it. But in Iran, Masih is a masculine name, another name for Jesus (it is mentioned in the Quran). I wasn’t thinking about defying Islam but wanted to be distinct and forge a new identity away from my conservative Islamic background. There were thousands of Masoumehs in Iran but I didn’t know of a female ‘Masih’.

At a Quran-recitation day at school, you recited dissident modern poet Ahmad Shamloo’s poem and were dragged out. Who initiated you into critical reading? And, which writers would you count as your favourite?

My brother Ali was a voracious reader, as was Mohsen my eldest brother. I picked up on their reading habits. I read and read non-stop. I used to debate with them so in order to beat them, I had to keep reading. I frequented book stores, even the ones run by the local mosques to find material to read.

My favourites include poets Shamloo and Forough Farrokhzad, whose poetry touches on how women have been judged throughout history, authors Simin Daneshvar and Ali Ashraf Darvishian, Romain Rolland (and his ten-volume masterpiece Jean Christophe), and Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05