Georgia: the region that pioneered wine making and floors visitors with its food

Everywhere you go in Georgia, you will find khinkali, a plus-sized dumpling, that will remind you both of momo and modak

The meat-filled khinkali (Photo credits : Gunjan Bharti)

The meat-filled khinkali (Photo credits : Gunjan Bharti)Have you eaten khinkali? Oh, you must try it.” It was one of those rare moments when a note of emotion had crept into Giga’s voice. Nothing could perturb our placid guide-and-driver in Georgia, it seemed, except our unfamiliarity with a Georgian delicacy. We reassured him that we had sampled a plate of khinkali on our first evening in Tbilisi, but we would certainly not mind having more.

“You eat meat? Khinkali is best when it has a filling of meat. It is delicious.” Giga paused as if wondering whether he should reveal a distasteful detail. “They make it with mushrooms also,” he said eventually – adding, with a grimace: “But that is not real khinkali.” (You can cross many borders and travel thousands of kilometres but you are never too far from the veg-biryani-is-not-biryani debate. Now, on our way to the Caucasus mountains, we were amused to discover an exotic version of a familiar grumble).

Shkmeruli, made with oven-roasted chicken in a garlic thyme sauce (Photo credits : Gunjan Bharti)

Shkmeruli, made with oven-roasted chicken in a garlic thyme sauce (Photo credits : Gunjan Bharti)

There was a solitary vegetarian in our travel party of four. The rest of us had no compunctions about eating mammals. Giga was pleased with this information. “We will cross a village called Pasanauri on our way,” he informed us, “Lot of people say it is the place where khinkali was first made. I know a great restaurant we can visit.”

Depending on your geographical location in the Indian subcontinent, the khinkali will either remind you of momos or modak. It is a plus-sized dumpling — as big as a toddler’s fist — and the filling inside is accompanied by a broth that can take you by surprise and spill onto your clothes. To avoid such mishaps, Georgians advise you to use both hands when eating khinkali, biting and slurping until all that remains is the doughy top knot. At the end of a meal, these clumps lie strewn across the plates, like trophies celebrating the appetite of the diners.

Giga’s observation about the Caucasus being the birthplace of khinkali is echoed across the internet. But a more credible version of the story holds that the dish owes its origins to the rampaging Mongol armies. The idea of dough-wrapped ‘parcels of meat’ likely travelled with these raiders from Central Asia to Georgia in the 13th century.

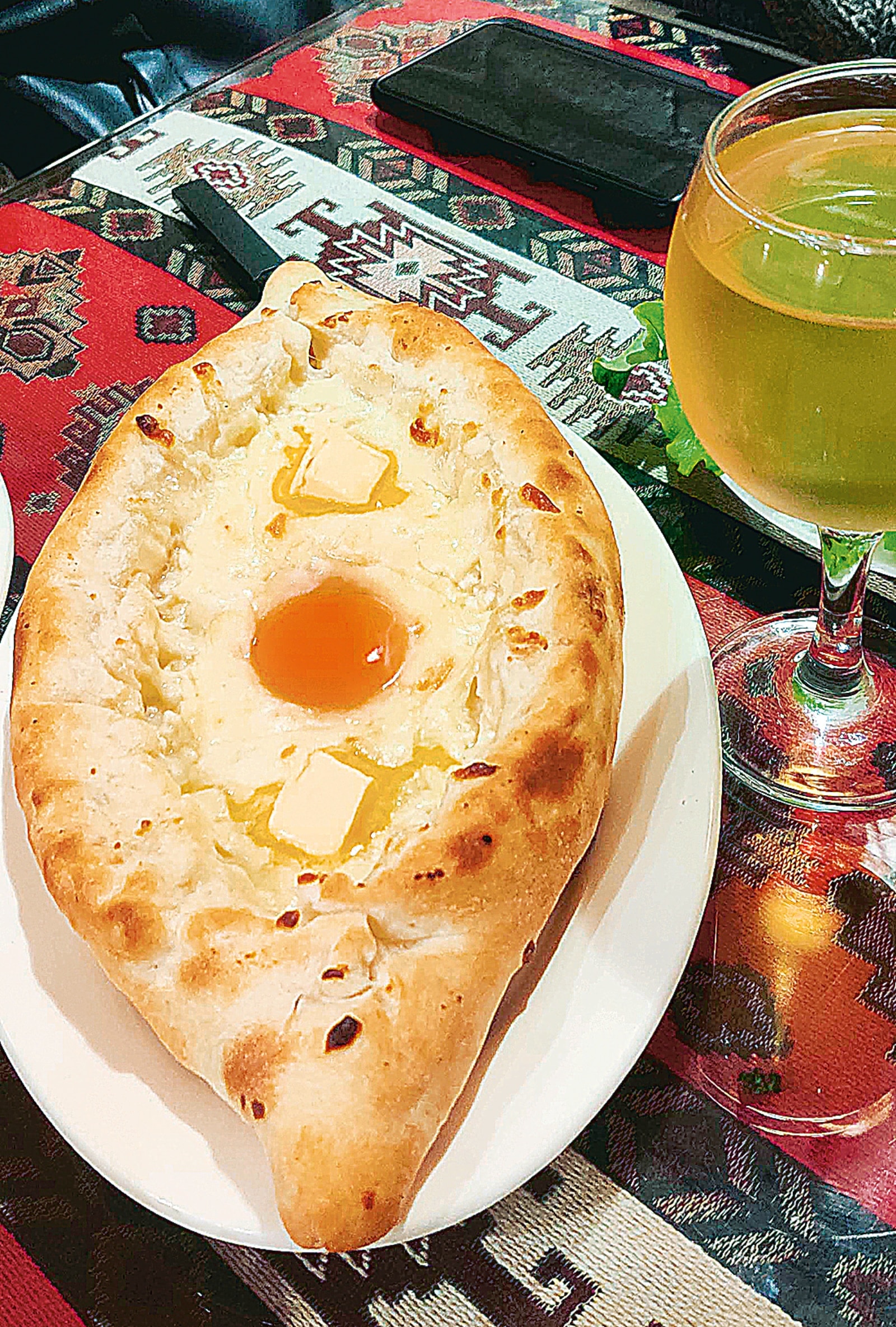

Regardless of its antecedents, khinkali is now a cultural icon of the land. In a cuisine rich in delicacies — the bread-and-cheese marvel that is khachapuri, the brothy shkmeruli — khinkali is feted as one of the crown jewels. It adorns socks, satchels and shirts. You can find it in water-colour tableaus and in carved fridge magnets. It is the most common motif in gift shops — its popularity, perhaps, rivalled only by wine.

Until I set foot in Georgia, I had no inkling about the copious variety of wine produced in the country or in their belief that wine making was pioneered in the region. But unlike the dubious genealogy of the khinkali, Georgian claims on wine stand on better footing. In 2017, archaeologists unearthed

evidence suggesting the local legends of millenia-old viticulture techniques may indeed be true. Pottery fragments discovered at excavation sites in the south Caucasus show that Georgians of antiquity were making and storing grape wine nearly 8,000 years ago. And as anyone visiting the country today can attest, in all these intervening years, the national affinity for the drink has not diminished one whit.

By some accounts, there exist over 500 types of indigenous grapes in Georgia. When you enter a typical Georgian wine store, and see the range of vintages on display, this number ceases to surprise. Most outlets allow patrons to sample the products but this offer can turn out to be a poisoned chalice. For those with philistine palates, for instance, a wine tasting soon becomes an overwhelming experience with the myriad flavours and notes mingling into a heady confusion. Such people are better served nursing a cup of the humble glintwine (mulled wine) as they explore the Christmas markets of Tbilisi. During our stay in the city, we often turned to this warm and spicy concoction to battle the December chill — a habit we shared with the protestors who would gather in front of the Parliament building every evening.

Khachapuri,a cheese-filled bread (Photo credits : Gunjan Bharti)

Khachapuri,a cheese-filled bread (Photo credits : Gunjan Bharti)

In the final weeks of 2024, Tbilisi witnessed a slew of citizen protests. This outcry was triggered by the Georgian government’s decision to halt negotiations to join the European Union. As a relatively young democracy that was occupied by Soviet Russia for nearly 70 years and achieved independence when the USSR fell in 1991, Georgia has pursued EU membership for years. It is a goal that has wide appeal — media reports indicate that around 80 per cent of Georgians favour the move. But the policies of the ruling party, labelled ‘pro-Russian’ by European news agencies, queered the pitch and led to a breakdown of the talks.

On New Year’s Eve, the usual procession of protestors streamed in, heading towards the Parliament. We were accustomed to seeing stalls selling flags and banners and glintwine, but this time there were new props on the road: long, feasting tables where the protestors could ‘share food and drinks, in a symbol of unity and togetherness’. A few hundred metres away from the heart of the convivial protest-feast, we marked the end of 2024 with a traditional Georgian dinner in a modest restaurant.

The place had an all-female staff, many of whom rushed out of the kitchen every few minutes to perform a folksy dance, accompanied by much clapping and hooting. Some patrons also joined in. A guitar appeared out of nowhere and was passed around. With such varied entertainment on offer, we did not mind waiting for our food. The charming milieu alone had made our last meal of the year a memorable one. But when dinner finally did arrive, we fell in love, once more, with Georgian fare. Khachapuri, mtsvadi, ajapsandali — we had our fill of it all. And along with the rest, there was, of course, our standard order of khinkali — the ones filled with meat, just as prescribed by Giga.

The writer is a Mumbai-based lawyer

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05