‘Photographing is a form of friendship’: Dayanita Singh

The winner of the 2022 Hasselblad Award, Singh on rejecting norms and dancing with her camera

Museum Bhavan, 2017, installed in Agra for a private event (Courtesy: Dayanita Singh)

Museum Bhavan, 2017, installed in Agra for a private event (Courtesy: Dayanita Singh)Sunday at a seaside lounge overlooking the Gateway of India. Tourists teem outside, patrons brunch inside, boats bob on a glinting sea. Taking it all in is Delhi-based photographer Dayanita Singh, 61, seated at a sunlit window. She has called for decafs and eggs on avocado toast as a treat. A celebration is in order. A retrospective, the launch of a new “photo novel”, and winning the prestigious Hasselblad Award — all have happened in under a year.

“At first, I thought somebody was playing a joke because I don’t work as a traditional photographer. In fact, I challenge it,” Singh says, recalling March 8, when the Hasselblad Foundation announced her as this year’s awardee. Since 1980, the foundation based in Gothenburg, Sweden, has recognised pioneering photographers who continue to develop artistically and who influence younger generations of photographers. Previous awardees include Ansel Adams, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and Nan Goldin. The award, which will be given at a ceremony on October 14, comprises SEK 2,000,000 (Rs 1.47 cr), a gold medal, a diploma, an exhibition and a symposium. Winners can choose the music for the ceremony, Singh says, and she has requested Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No 1 – Second Movement. Much to her surprise and delight, an orchestra will be arranged.

Singh in her hostel room at NID, Ahmedabad, in the 1980s (Courtesy: Dayanita Singh)

Singh in her hostel room at NID, Ahmedabad, in the 1980s (Courtesy: Dayanita Singh)

By choosing Singh — the first laureate from South Asia — the Hasselblad Award nods to the limitless physical means of displaying and disseminating photographs. Singh has eschewed the traditional exhibition format of prints displayed on a wall; instead of “fossilising a “single image” behind a frame, she prefers working with multiples, allowing images to play off each other; but, most importantly, she loves bookmaking.

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

At times, it would seem that Singh is a bookmaker who has chosen photography. Other times, bookmaking seems like a broad category for her works. Sent a Letter (2008) opens out as accordion folds. Kochi Box (2016) has loose image cards in a wooden frame that can be rotated like in a daily calendar. In most cases, the viewer/reader is encouraged to interact and toy with her books, book objects and portable “museums”. Photographs are her building blocks, not the final product.

In 2000, Singh made Myself Mona Ahmed, a “visual novel” of her friend, the late Mona Ahmed, who she first met while on assignment in 1989. Singh says, “Someone asked me who would be interested in one person and that I should have done something on the hijra community.” Singh stuck to her beliefs and the book isn’t a journalistic or anthropological study of a transperson but about friendship.

“Photographing is a form of friendship,” Singh says. “I never try to take the mickey out of someone or make someone look awkward. There is no hostility.” Indeed, the camera’s gaze can be a violent weapon that otherises people but Singh uses it with tenderness. Such is the case with Let’s See, her newest book of her oldest photographs from the 1980s and ’90s, when Singh began shooting. Let’s See and its special editions were launched at gallery ARTISANS’ in Mumbai in August, with another launch at Delhi’s Raw Mango on September 17.

A photograph from Let’s See highlights Singh’s interest in gestures and connections (Courtesy: Dayanita Singh)

A photograph from Let’s See highlights Singh’s interest in gestures and connections (Courtesy: Dayanita Singh)

Given Singh’s renown as a photographer, Let’s See could have easily been an indexed memoir of her early days. Singh resists this obviousness. Instead, we have a “photo novel”— a wordless, non-chronological string of images, from which readers get to plot their own narrative, like one would with poetry tiles. Singh’s longtime publisher Steidl takes the “photo novel” concept further — Let’s See is printed on paper used for novels and sized like a literary paperback.

Within its pages are characters who feature in her other works — Mona, tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain, her mother Nony Singh. Former DGP of Punjab, KPS Gill, who also appears here, “is certainly no friend,” Singh says, “but nothing happened without a conversation. A lot of time was spent with these people here — some more than others — but photography was part of the conversation. I was never there as a photographer. I was in conversation and I took a photograph.” With the several unnamed notable celebrities, especially from Hindustani classical music, one may indulge in a game of guess-who, but that’s not the book’s purpose. Let’s See is a fine instance of Singh’s visceral interest in the human body. People embrace, kiss, lean on each other, raise eyebrows, hold hands — the natural choreography of the human body unfolds here. Singh says, “I love people connecting, the gestures they make with each other to stay connected.”

Singh shot Let’s See on her first camera, a Pentax ME Super. She switched to a Hasselblad in 1997. The Hasselblad camera is named after its inventor, Victor Hasselblad (on whose birthday the awards are announced), and the brand has been associated with some of the most iconic images in history, such as the first landing on the moon. For Singh, the Hasselblad meant shooting from the level of the navel instead of the eye. It meant that she had the advantage of photographing even while being locked in conversation, “The Hasselblad became a part of my body and that’s why I used to call it my third breast,” she says.

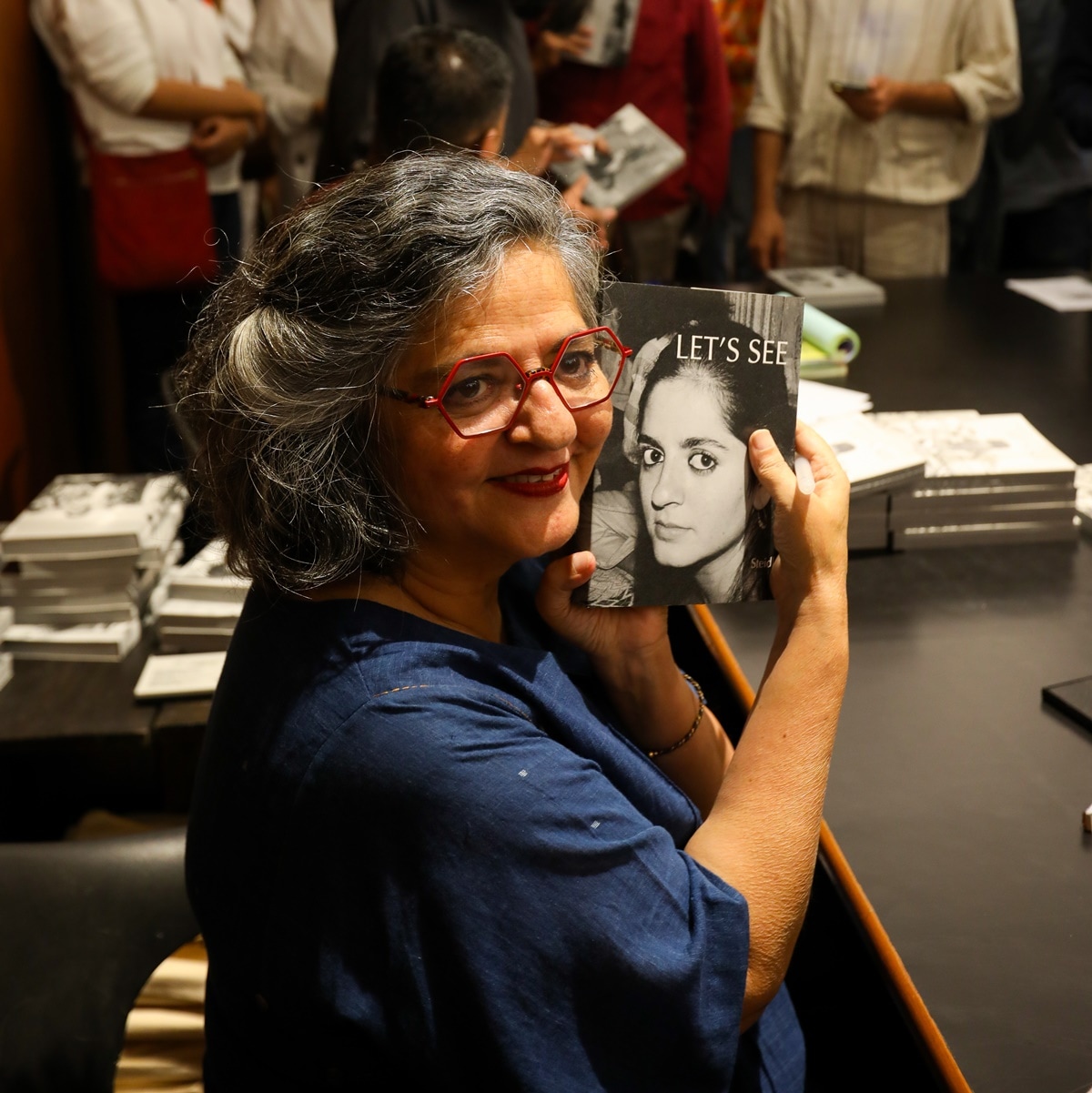

Singh at the Mumbai launch of Let’s See. Credit – Tina Nandi

Singh at the Mumbai launch of Let’s See. Credit – Tina Nandi

Let’s See was made for her recently-concluded retrospective, “Dancing with my Camera” at one of Berlin’s premier exhibition spaces, Gropius Bau. On Let’s See’s cover is Singh seated on her bed in the hostel room at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, where she studied. Spread around her, like a merchant with her wares, are dozens and dozens of contact sheets. Looking at them, it is easy to see how the form of the contact sheet is a prominent motif in the architecture of her book objects, portable “museums” and the display of her images, such as those at Gropius Bau.

Plans are in motion for the coming days — a portion of the award money will support critical writing on photography and research on the photo-book. A part of her award has gone towards People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), which announced the first Dayanita Singh-PARI Documentary Photography Award of Rs 2 lakh to photographer M Palani Kumar last week.

From her earliest years to the retrospective to the award, Singh has come full circle in 2022. The interview over, she hops into a taxi to meet some of her oldest friends in the city. There is a skip in her step, a sprightly mood to the day. It’s clear — brunch is over, but the celebration continues.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05