Award-winning poet and playwright Lemn Sissay on his lost childhood and a life unmoored

The British-Ethiopian writer talks about his poems — on splinters, longing and hope — the power of forgiveness, the struggle to find his family and to reclaim his sense of worth

Lemn Sissay at the festival in Jaipur

Lemn Sissay at the festival in Jaipur

His favourite hero, says British-Ethiopian poet, playwright and broadcaster Lemn Sissay, has never been the knight in shining armour, that infallible legend who steps in neatly to save the day against all odds. Instead, he’s found comfort in the battle-scarred orphan, whose hardscrabble life has welded loss and loneliness into rage and resilience.

“Jane Eyre was adopted, Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights was an orphan, Harry Potter was a foster child, Superman was adopted, Cinderella was kinship fostered by her sisters, Rapunzel had no parent. We are front and centre of popular culture. There’s something special, something specifically deep about the experiences of young people who are without family and I want others to see that,” he says, with great animation.

It has taken Sissay, winner of the 2019 annual PEN Pinter Prize, a good part of his 52 years to come to this realisation. His dystopian childhood was spent in a quagmire of state intervention — born to an underage Ethiopian mother, who had come to the UK to study, he was placed in foster care two months after he was born. Despite his mother’s refusal to sign adoption papers — she wanted him back, she insisted — the social worker assigned to his case assured his foster family that they could treat it as an adoption. He even lent Sissay his name: he was called Norman after him. At 12, when he’d begun to show the first streaks of rebellion, his foster family, now with children of their own, decided they did not want him any more. He was sent back to social services and moved from remand home to home, suffering abuse and racism, each experience hardening the despair that somehow he deserved this. When he finally came of age, Sissay would discover that all of it had been a big lie. That his mother had written to social services, begging them to return her child, to let him grow up among his own people. He would also discover his name: Lemn, which, in Amharic — the official language of Ethiopia — means “why”.

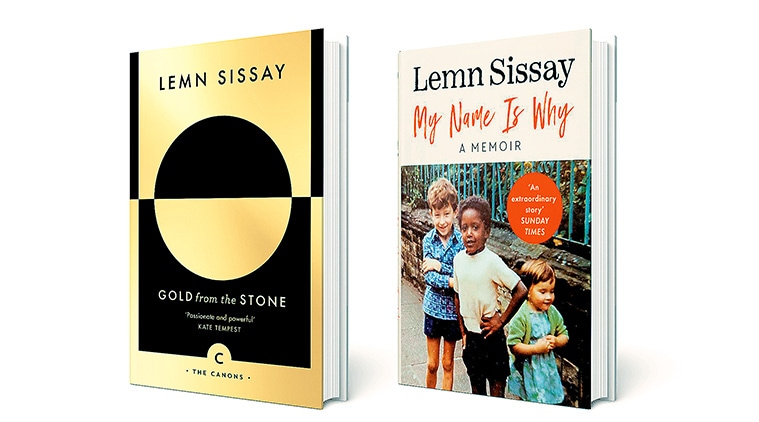

The covers of Lemn Sissay’s books

The covers of Lemn Sissay’s books

“How does a government steal a child and then imprison him?” he writes in the preface to his searing memoir, My Name is Why (2019). “How does it keep it a secret? This story is how.” Through a narrative that packs in his reports from the childcare system, his psychological assessments and his redemptive poetry, Sissay builds up a picture of a lost childhood and a life unmoored.

The evening has settled over the penultimate day of the Zee Jaipur Literature Festival. At one of the last sessions of the day, Sissay and a host of others, that included English poet Simon Armitage and the Australian-Eritrean poet Manal Younus, had captivated the small gathering with their very different, very dynamic energies. Sissay performs poems on splinters and longing, but, mostly, of hope. The applause that follows the performance is full-hearted, but afterwards, he is keen to know if it meant anything to us, the audience, so far removed from his life experiences? “Poetry is a cautious confession. It is the greatest translator of the heart — whether that is a disturbed heart, whether that is a heart full of holes, a bleeding heart,” he says.

Sissay was the official poet for the London 2012 Olympics but his tryst with poetry and performance began early in life. At 17, he had self-published his first poetry pamphlet, Perceptions of the Pen. Later, he moved to Manchester, where he worked as a literature development worker at a community publishing house, and where he is now the chancellor of the University of Manchester. His first collection, Tender Fingers in a Clenched Fist, came out in 1988. There would be many more award-winning volumes of poetry, production and plays after that, including Gold From the Stone (2016), and the plays, Something Dark (2006), Why I Don’t Hate White People (2011).

In his poetry and his plays, Sissay has drawn over and over from his life’s experiences. “When they took away his mother/ He was determined to survive./ When he found his father dead/ He clenched his breath to stay alive./ When they took away his name/ He called himself free/ People close by would say/ What a strong boy he must be./ When they took away his home/ He found it in his heart. And it only took a few more years/ For it to blow his mind apart,” he writes in the poem, Time Bomb.

A few years before the memoir, a one-off show in London, The Report (2017), had been structured on the psychologist’s report about the traumas a young Sissay underwent in the care system and his reactions to it. His struggle with mental health continues, but writing, he says, is both purge and protest. Is his story near completion now? “I don’t think any of our stories are complete. We are a work in progress. I think I am trying to share my story so that others may appreciate their own stories. Mine is one of loss, one of theft. I was stolen from my family and I hope that when people read my story, they understand their own stories, their own complex relationships with their families,” he says.

The crests of his creative life has been matched by the troughs of his near-three decades’ struggle to find his family and to reclaim his sense of self-worth. He finally met his mother at 21. By then, she was working with the UN in Gambia. She had a family of her own. His father, he found out much later, was a pilot with an Ethiopian airlines, who’d passed away before he could meet him. There was also the long, legal battle to reclaim his files from social services. In 2015, he finally got the files, an inadequate apology and compensation for the years of damage. It wasn’t enough but Sissay says he has finally taught himself to forgive. “Forgiveness is never easy but it’s important. Did I feel anger? I was livid with what happened to me. But how long can you hold on to such anger? The power of forgiveness is immense. The event which you felt you could never forgive is the event that we must forgive. Because we can carry the anger, the bitterness for all of our lives, we don’t realise it, but it changes us. Every relationship we have, every friendship, it changes how we act with everybody,” he says.

In his role as a chancellor, he is around young people a lot. He is also engaged in rehabilitating children who have come out of the care system. What does he tell them about self-care? “I believe that anger is an expression in the search for love. So, I see anger and I can see its beautiful explosion. But if you hold on to that anger above everything else, it won’t turn itself in. So, to young people I say, express yourself as best you can, be open, be honest, be truthful, angry, happy, loving, confused; get it wrong. But as long as you can learn from them, it’s fine,” he says.

His family is now the artistic community. “And myself. I have got to be my own best family. It’s good when when you have a problem to say to yourself what would my favourite aunty say, what advice would my mom give? I think we are all trying to find ourselves as our best family member,” he says, adding, “I try to live in the present as best as I can. I should remind myself to do that more.”

How does he do it? I ask him. Sissay smiles and shakes his head. He’s thought about it, too. “‘How do you do it?’ said night./ ‘How do you wake and shine?’/ ‘I keep it simple,’ said light./ ‘One day at a time.’ (Epitaph)”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05