The shift that triggered the term was the removal of hundreds of Osho’s (Bhagwan Rajneesh’s) photographs that had once greeted every visitor and sannyasin at the entrance gates and beyond. At their place appeared Osho’s cryptic signatures, framed and displayed like minimalist art pieces. This happened around 2000.

For many followers — especially the faction that broke away from the main Pune commune around 1999–2000 — this stood out as the most stark and unambiguous symbol of transformation since Osho’s death on January 19, 1990, amid numerous other subtler shifts.

Another quiet but significant departure was the discontinuation of “celebrating” his death anniversary, once held regularly at the OIMR in line with Osho’s teaching that death should be met with joy and festivity. It added to the general feeling of discomfort amongst the many factions of followers outside the Pune commune.

As the resort continues to reinvent itself and court new controversies, how much of the master’s legacy truly survives? His epitaph at the OIMR still reads: “Never born, never died, only visited this planet from December 11, 1931, to January 19, 1990.” But after 36 years, what endures, and what has changed irrevocably?

The background

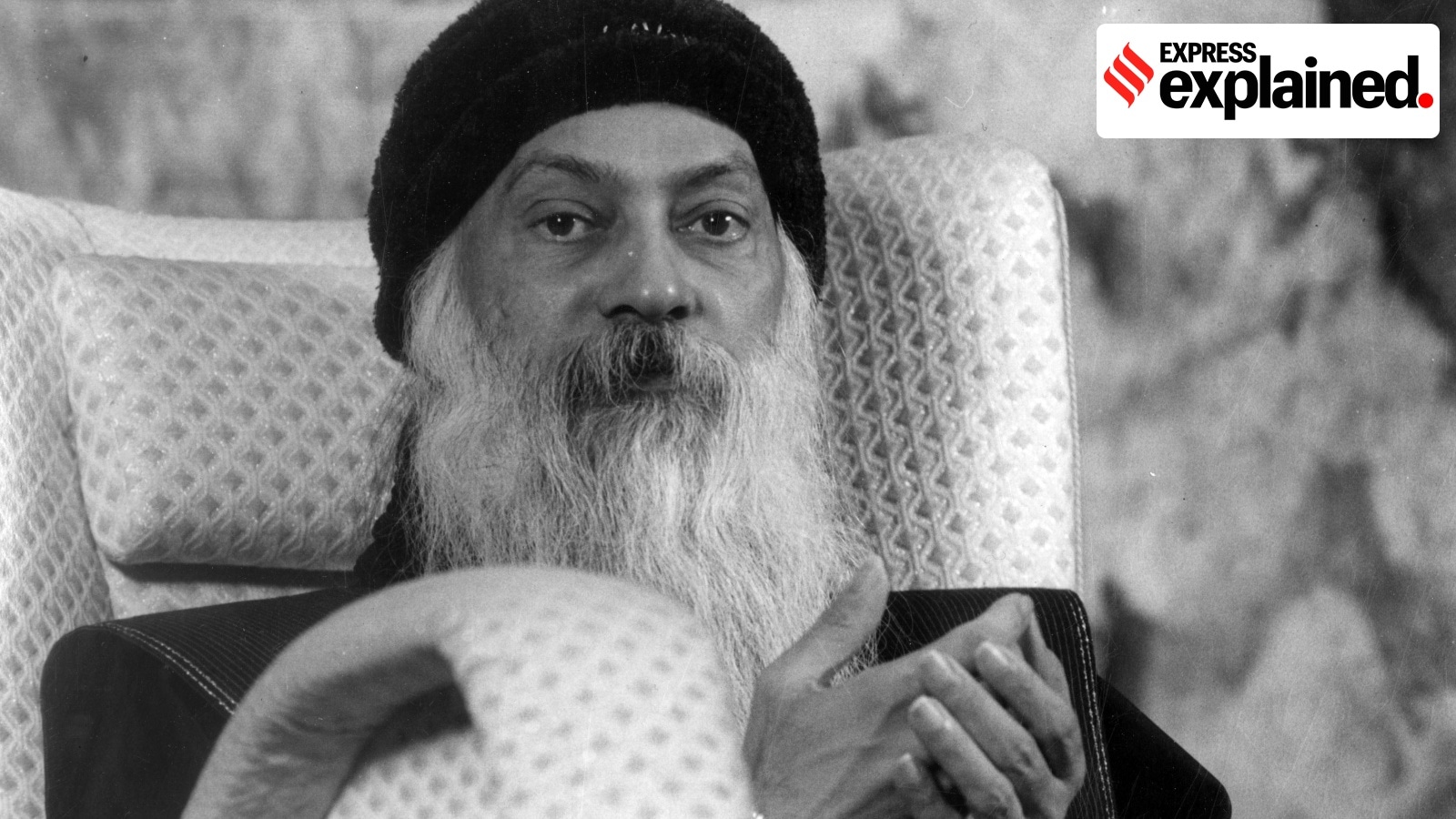

Born Chandra Mohan Jain in Kuchwada, Madhya Pradesh, on December 11, 1931, Osho embarked on his path of radical mysticism after attaining “enlightenment” at age 21. Holding a master’s degree in philosophy, he travelled across India, first as Acharya Rajneesh and later as the better-known Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.

His teachings blended Sufism, Taoism, Zen, and more, emphasising meditation, individual freedom, and sexual liberalism. He established his first ashram in Pune on March 21, 1974, calling the city “the centre of the universe spiritually”. The orange-robed (later maroon) sannyasins, mostly foreigners, roamed the streets, sparking both intrigue and controversy in the conservative Cantonment town of Pune, until Rajneesh moved to the United States in 1981.

Story continues below this ad

In Oregon, he founded Rajneeshpuram, 40 km away from the city of Antelope. As detailed in the Netflix documentary Wild Wild Country, those ostentatious years were marked by power struggles, clashes with locals, the much-talked-about fleet of 93 Rolls-Royces, the takeover of Antelope (renamed City of Rajneesh) and serious controversies that led to criminal charges against Osho and finally his deportation in 1985.

Osho returned to India and, on January 4, 1987, re-established the ashram in Pune’s toniest area — Koregaon Park. He lived there, still controversial, still rebellious, until his death on January 19, 1990, from an illness that continues to be shrouded in mystery.

The controversies

Death did not put an end to controversies surrounding the Osho commune — they just took on new forms.

The first major schism occurred around 1999–2000 when a large group of core followers broke away and established their own centres — some strengthening the Osho centre in New Delhi, others starting new ones in places like Dharamshala. This “rebel” group also became a kind of watchdog, opposing what they saw as dilution of Osho’s legacy and various contentious issues at the commune.

Story continues below this ad

These included the trademark battle over “OSHO” between the Zurich-based Osho International Foundation (OIF) and Delhi-based Osho Friends International, with OIF losing exclusive rights in 2009. In 2013, a purported “Will” surfaced 23 years after Osho’s death, naming a Swiss trust as beneficiary of his property and intellectual rights. The rebels called it fake; forensics in India supported their claim, and the issue faded.

Other disputes involved banning followers wearing the Osho mala, with his picture — once almost mandatory — from entering the commune and allegations of digital censorship, with OIF reportedly taking down Facebook pages of external Osho groups, alleging copyright infringement, a practice many say continues.

The latest controversy was the 2023 attempt to sell two plots of land (about three acres) to businessman Rajiv Bajaj for Rs 107 crore, citing Covid-induced financial constraints. The Charity Commissioner stayed the sale in December 2023 after a petition was filed by disciple Yogesh Thakkar.

The changes

Post-1990, ownership transferred to a 21-member Inner Circle Osho, including five Indians and his physician, Swami Amrito. Over time, critics allege control shifted to an even smaller group that remains somewhat undeclared.

Story continues below this ad

“The Pune Commune should logically be the world headquarters of the Osho Movement, but the Osho International Foundation is headquartered in Zurich, Switzerland,” said Abhay Vaidya, author of the 2017 book Who Killed Osho that has just made its screen debut on YouTube. Still a regular visitor to the commune, Vaidya rues that the Zurich body “controls all of Osho’s and the commune’s intellectual properties through copyrights and trademarks from Zurich, with a marketing office in New York”.

Swami Chaitanya Keerti, who left in 2000 after the 40-day Millennium celebrations at the commune from December 11, 1999, to January 19, 2000 (also the last death anniversary event), and who was also the editor of Osho Times (Hindi), noted how the magazine quickly folded soon after. He adds pointedly that the magazine always had Osho on the cover. “Up to 1998, Osho videos were telecast on satellite channels—never after that, because copyrights are registered in Zurich and the USA. So, no Osho discourses on TV for 28 years. The new generation missed seeing Osho. Now he’s visible again on social media and YouTube, but OIF Zurich keeps deactivating our Facebook accounts,” he alleged.

Vaidya and Keerti highlight the missing Osho photographs, no mention of his “samadhi” on the website or literature, discontinuation of anniversary celebrations, declining daily visitors, and property sale attempts — contrary to Osho’s vision of expansion, even buying all of Koregaon Park, to make a case for what NYT had called “de-Oshoization” over two decades ago, the biggest change and complaint of the Osho groups outside Pune.

“The energy is completely missing from the Osho Commune, his Karma Bhoomi,” Vaidya added. Others have posted on social media that the resort seems detached from Osho, though it rests on its teachings. Others have called it more like a “health club.”

Story continues below this ad

Indeed, keeping to its resort avatar, the commune designed by Hafeez Contractor and spread over 40 acres with 12 acres of landscaped gardens, futuristic auditoriums, swimming pools and cafes, has been pitched a tad like that on its website when it says, (albeit quoting Osho) “We can create the biggest and the most beautiful spiritual health club in the world. A kind of Club Med, spiritual Club Med, as in Meditation.”

Ma Sadhana, OIMR spokesperson, defends the changes as aligning with Osho’s vision. “Legacy belongs to the past and is carried into the future. Osho’s effort is to demolish the past so we can live today. We are doing it. His vision is to give birth to a new man and a new woman… The OIMR is a breeding ground for new human beings, with hundreds of Osho meditations, meditative therapies, work as meditation, and a celebrative lifestyle. No division of caste, creed, nationality, or religion. Thousands visit from around the world. Younger people in their 30s and middle-aged visitors come for short meditation and relaxation. This is a happy place.” She adds that those in the commune get that, the detractors outsider don’t.

The constants

What remains undoubtedly constant is interest in Osho — especially his dynamic meditations, audio/video discourses, and books, now viral on social media and all the activities that continue at the resort’s Multiversity. Also, many Osho centres exist worldwide, holding group meditations, workshops, dancing, and events around his birth, death, and enlightenment day on March 21, all of which reiterate his unique blend of celebration and meditation.

At the Pune commune, mega celebrations may have reduced to twice yearly — in monsoon and winter — but the diverse courses in healing arts, esoteric sciences, creative arts, Tantra, Zen, Sufism, and meditative therapies are still a draw. The samadhi, by any other name, continues to attract followers. While the Covid pandemic saw a massive dip in numbers, since then they have been steadily rising and were reportedly up to 18% last year compared to 2024.

Story continues below this ad

For most, though, the place is one that is still seemingly closed, inaccessible and far removed from the world outside, a feeling reinforced by its regular controversies. Clearly, while the mystique endures, the mystery has deepened.