© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

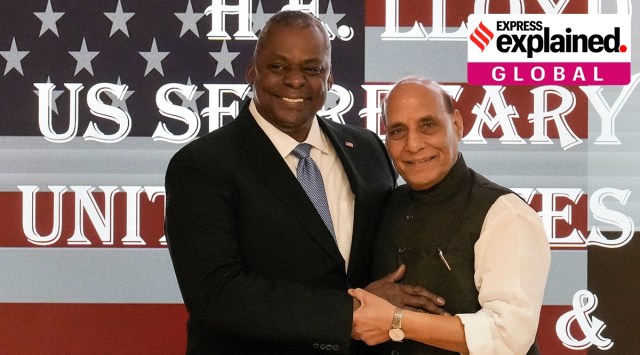

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh with US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin before a bilateral meeting in New Delhi on Monday, June 5. (PTI)

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh with US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin before a bilateral meeting in New Delhi on Monday, June 5. (PTI) As Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares for his June 21-24 official state visit to Washington DC, India and the United States are said to be looking at “consecrating” their relationship premised on greater alignment of goals in Asia and the Indo-Pacific.

At the same time, the US appears to be inching towards a detente with China. After months of trying, Secretary of State Antony Blinken may be finally welcomed in Beijing in the coming weeks for what American media are describing as an effort by the Biden Administration to ease strained ties.

Blinken called off a scheduled visit to China in February after a Chinese high-altitude balloon appeared above the US, and was ultimately shot down on President Joe Biden’s orders. The Pentagon said the balloon was a spying device, while China claimed it was a research airship that had blown off-course.

US-China tensions have been high since the time of the Covid-19 outbreak. China’s suspicion that the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue is a mechanism to contain it in the Indo-Pacific, and the proactive US positioning on Taiwan — with then Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August 2022 visit — did not help matters.

But over the last couple of months, the US has made efforts to reschedule Blinken’s visit — even as the Chinese have played hard to get. At the annual Shangri La Dialogue last week, Chinese Defence Minister Li Shangfu — whom the US has sanctioned — refused a meeting with Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin.

It has emerged that CIA Director Bill Burns, a trusted confidant of Biden, made a secret visit to China last month, where he reportedly met with officials to stabilise the relationship and prevent a possible open conflict. Burns “emphasised the importance of maintaining open lines of communications in intelligence channels”, The Financial Times reported.

Also in May, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan met Wang Yi, the former Foreign Minister who is now Director in the Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission, in Vienna. The discussions continued for more than eight hours on May 11-12, and news of the meeting was made public only after it ended.

In a background press briefing, a senior White House official said both sides “have sought to increase high-level engagement in order to maintain channels of communication” and “manage competition”. Sullivan was said to have conveyed that the US is “in competition” with China, but it “does not seek conflict or confrontation”.

The talks were “constructive” and “candid”, both sides recognised that the balloon incident had led to an “unfortunate pause” in engagement, and “we’re seeking to move beyond that and reestablishing just standard, normal channels of communications”, the official said.

At the G7 meeting in Hiroshima, President Biden himself appeared to suggest a change of approach. G7 leaders used the word “de-risk” for their economic engagement with China instead of the more combative “decouple”, and Biden said the US was “not looking to decouple from China”, but rather to “de-risk and diversify our relationship”. He told reporters that “in terms of talking to [China]”, a “thaw” was expected “very shortly”.

During the Cold War, the US and USSR worked out a modus vivendi after coming close to a nuclear conflict during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. The détente, as it came to be called, reduced tensions and led to a period of cooperation, even as proxy conflicts played out in the superpowers’ respective spheres of influence.

In an interview to The Wall Street Journal on the occasion of his 100th birthday, Cold War strategist Henry Kissinger, one of the architects of the original détente, suggested that an accommodation with China might look very similar to the one the US reached with the Soviet Union.

“The most important conversation that can take place now is between the two leaders, in which they agree that they have the most dangerous capabilities in the world and that they will conduct their policy in such a way that the military conflict with them is reduced,” Kissinger said.

Economic engagement forms a substantial part of the US-China relationship. Bilateral trade was almost $700 billion in 2022. The US imports more from China than any other country. American companies have long seen China as a top investment destination, although that may be changing now. Apple’s Tim Cook, JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon, and Tesla’s Elon Musk have recently visited Beijing; Citi CEO Jane Fraser was there on Wednesday.

If Blinken does visit China — Global Times has suggested it is a rumour and “US media hype” — a Biden-Xi summit could follow as a step towards finding a modus vivendi, if not rapprochement, between the two powers.

Over the last few years, the US and India have grown closer over a shared perception of China’s rise. India’s embrace of Quad and the US Indo-Pacific strategy came after the Doklam standoff in 2018 and the PLA incursions into eastern Ladakh in 2020. The US sees India as a major part of its endeavour to build a regional coalition against China. But how would an improvement in US-China relations play out in a region where India is the country with the longest land border with China — and what options might India have?

The Cold War rivals mostly accepted each other’s spheres of influence. Asked if a US-China détente might lead to a situation in which India would have to accept a China-centric regional order, Kissinger told the WSJ that “the ideal position is a China so visibly strong that that will occur through the logic of events”.

Happymon Jacob, professor of international relations at Jawaharlal Nehru University, said a US-China accommodation of “the kind Kissinger has been pushing for” would be “counterproductive” to India’s interests. “India’s worst nightmare in the years to come would be the emergence of a US-China G2 for global stability, with each side indirectly accepting each other’s spheres of influence,” he said.

Former Ambassador to China Ashok Kantha said India cannot let its broad-spectrum strategic partnership with the US be defined primarily by China.

Differences between the US and China were deep-rooted and fundamental, he said: “Any attempt at accommodation can only be limited to tactical measures, putting in place guardrails and reducing the risk of military conflict which neither side wants. Neither is interested in addressing structural problems in the relationship.”

Kantha pointed to bipartisan concerns in the US about China as the “pacing threat” and primary strategic challenge as one reason why Biden may not be able to stray too far from the assertive messaging on China so far. On the Chinese side, Xi has publicly stated that the US-led West wants to contain and suppress China.

“India needs a counterbalancing strategy vis-à-vis China, which will involve working with the US and others with shared concerns about the country while retaining its own agency. There has to be clarity on the limitations of such strategic alignment, how far India is willing to go, and how to manage expectations on both sides,” Kantha said.