A temporary provision

Article 370 is in Part XXI of the Constitution, titled “Temporary, Transitional and Special Provisions”. Article 370 is titled “Temporary provisions with respect to the State of Jammu and Kashmir”.

370(3) reads: “Notwithstanding anything in the foregoing provisions of this article, the President may, by public notification, declare that this article shall cease to be operative or shall be operative only with such exceptions and modifications and from such date as he may specify: Provided that the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly of the State referred to in Clause (2) shall be necessary before the President issues such a notification.”

A commonly held view is that since the Article itself provides for the process through which it can be declared inoperative, it is a temporary provision and that the framers of the Constitution never intended for the special provision to be a permanent feature.

However, the petitioners argued that it is not for this reason that Article 370 is referred to as a “temporary” provision.

Permanence of Art. 370

While the Constitution of India came into force in 1950, the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir came into being only in 1951. Yet, Article 370(3) makes a reference to the “Constituent Assembly of the State”.

Story continues below this ad

Clause (3) of Article 370 provided that any change to the relationship between the State of Jammu and Kashmir and the Indian Union could only be brought about on the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly.

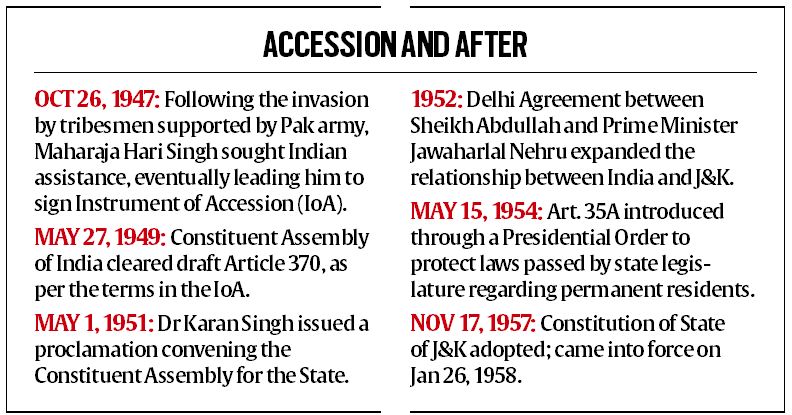

The Constitution of J&K was adopted on November 17, 1956, and came into effect on January 26, 1957. After this, the Constituent Assembly ceased to exist. Sibal argued that the seven-year period during which the Constituent Assembly was given power to recommend changes to Article 370 is why the provision is called “temporary”.

“…Once the Constituent Assembly created the Constitution for the State, and then ceased to exist after its tenure from 1951-1957, the Article became a permanent feature of the Constitution,” he argued.

This was part of Sibal’s argument that Parliament could not have abrogated Article 370 after 1957 because it could not have sought the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly once it ceased to exist.

The situation after 1957

Story continues below this ad

CJI D Y Chandrachud asked how Article 370(3) would work post 1957 when the Constituent Assembly had ceased to exist. The line of questioning included whether the “substantive part” of Art 370(3) — which gives power to the President to notify that the provision ceases to operate — would still remain.

To this, Sibal replied that the President’s power to issue such a notification could only be valid when the Constituent Assembly existed. Simply put, Parliament’s power to tinker with Article 370 expired after 1957.

The petitioners’ argument is that as a political formula, it was agreed to have a Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir for a “collaborative relationship” with India. Till then, the Constituent Assembly was given powers to change the course of Article 370 which determined India’s relationship with Jammu and Kashmir.

(This is the first of a series that will explain key issues that are taken up by the Supreme Court as the hearing continues.)