From pioneering microfinance to heading Bangladesh’s interim govt: Story of Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus

From winning the Nobel that made him one of the world’s most famous Bangladeshis to facing the heavy hand of Hasina’s hostility to being chosen by the students who ultimately pulled her down, Muhammad Yunus has traversed a remarkable arc. At 84, he begins a new job, that of reuniting his bruised, divided country.

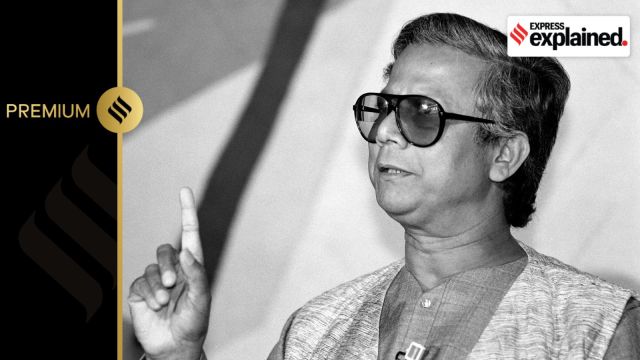

Muhammad Yunus arrives at the Bangabhaban in Dhaka on Thursday to take oath as Bangladesh’s Chief Adviser. (Reuters)

Muhammad Yunus arrives at the Bangabhaban in Dhaka on Thursday to take oath as Bangladesh’s Chief Adviser. (Reuters)In 2009, Muhammad Yunus said at The Indian Express Idea Exchange that he had recently refused an invitation to head a caretaker government [during 2006-09 when there was no elected government in Bangladesh].

He had, however, allowed himself to be persuaded to float a political party. It had not worked out. Yunus said: “The people I wanted, didn’t want to join me and the people who were surrounding me, I didn’t want them.”

A decade and a half later, the 84-year-old “father of microfinance” took oath as Chief Adviser to the interim government of Bangladesh — presumably on his own terms. The young protesters who had brought down Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year regime wanted him to take charge of the country.

The microfinance idea

Yunus got his PhD in economics from Vanderbilt University in 1971, the year Bangladesh was born. During the Liberation War, he worked with civil society in the US to build support for Bangladesh’s freedom from Pakistan.

After returning to his country, Yunus worked briefly at the Planning Commission before joining Chittagong University as head of the economics department. It is here that he developed his ideas about microfinance.

“In 1974, I found it difficult to teach elegant theories of economics in the university classroom, in the backdrop of a terrible famine in Bangladesh. I felt the emptiness of those theories in the face of crushing hunger and poverty,” he said in his Nobel acceptance speech in 2006.

He recalled his meeting with a poor woman who had borrowed less than a dollar from the local moneylender on the condition that he would have the exclusive right to buy all her produce at a price decided by him. It was “slave labour”, Yunus said.

He found 42 such “victims” who together owed the moneylender about $27, and cleared their debts with his own money. And thus were sown the seeds of what would later become Grameen Bank.

“If I could make so many people so happy with such a tiny amount of money, why not do more of it?” he said.

The Grameen Bank story

In 1976, Grameen Bank was launched as a research project in a village in Chittagong. It became a full-fledged bank in 1983, aiming to provide collateral-free, low-interest credit to the poor, women, and socially and economically marginalised sections. Loans were disbursed to groups of borrowers, with the whole group acting as co-guarantors.

As of June 2024, Grameen Bank operates in 81,678 (around 94%) of villages in Bangladesh, serving almost 45 million people through 10.61 million borrower members, 97% of whom are women. Since its inception, the bank has disbursed $38.66 billion in housing, student, micro-enterprise, and other loans, and has a recovery rate of more than 96%, according to figures on its website.

The Grameen initiative has spread beyond microfinance, and today has a number of for-profit and nonprofit ventures, targeted at the rural poor in sectors ranging from fisheries to software, education to telecom, FMCG to energy. Yunus is seen as a pioneer for “social businesses”.

The Grameen Bank model has been replicated across the developing world as a way to operate sustainable development initiatives with women at their centre. “Poor people are like bonsai trees… Society never gave them the base to grow on. All it needs to get poor people out of poverty is for us to create an enabling environment for them,” Yunus said in 2006.

Criticism of microcredit

But this model has its critics. Several economists say microfinance traps the poor in a cycle of debt from which they struggle to get out. In the end, all the negatives of traditional lending afflict microfinance too, from aggressive debt collection tactics to high interest rates.

“For people living in extreme poverty…we found families faced increased vulnerability owing to rising levels of indebtedness leading to loss of land assets as well as erosion of social capital resulting from diminished bonding social capital,” ethnographers Subharata Bobby Banerjee and Laurel Jackson wrote in ‘Microfinance and the business of poverty reduction: Critical perspectives from rural Bangladesh’, published in the journal Human Relations in 2017.

Yunus has countered that the problem does not lie with his model. “The concept of microcredit was abused by some and turned into profit-making enterprises… I felt terrible that microcredit took this wrong turn,” he told Bloomberg in 2022.

Hasina, Yunus, and after

Among Yunus’s harshest critics was Sheikh Hasina, who frequently accused him of “sucking blood from the poor”. Some of her anger was likely personal — and went back to Yunus’s plan to float his own political party in 2007.

Yunus had declared his intention just as the military started a crackdown on political parties, arresting many top leaders for alleged corruption. Hasina herself would be put in jail. She apparently never forgave Yunus for what she saw as a ploy to remove her from politics, striking when she was down. Yunus has always denied these allegations.

Many believe Hasina also saw Yunus’s post Nobel Prize popularity in Bangladesh — rivalling, if not surpassing, her own — as a threat.

After assuming charge in 2009, Hasina launched a series of investigations into Yunus and his Grameen group. She accused Yunus of forcefully recovering loans from poor rural women. In 2011, Yunus was unceremoniously removed as managing director of Grameen Bank on the pretext that he had exceeded the mandatory age of retirement.

A number of other cases followed — all of which, Yunus and his supporters say, were politically motivated. In 2013, he was put on trial for receiving money — including his Nobel Prize and royalties from a book — without permission from the government.

In all, over a period of 10 years of Hasina’s rule, 174 cases were filed against Yunus — including for violation of labour laws, money laundering, and corruption — the Bangladeshi English daily New Age reported in September 2023.

In January this year, he was sentenced to six months in prison for labour law violations. This conviction was overturned earlier this week, Reuters reported. In June he was indicted on embezzlement charges in a separate case.

It is unclear how all these legal cases will proceed, now that Hasina is out of power and Yunus is the head of the government.

What comes next

A difficult road lies ahead for Yunus. Following Hasina’s ouster, Bangladesh has seen a spate of attacks on minorities, and escalating sectarian tensions. In his first comments after arriving in Dhaka from abroad, Yunus described Bangladesh as a “family” and said the first task was to reunite it.

Also, the interim government is guaranteed by the Bangladesh Army, and Yunus effectively operates on the mercy of the generals who ultimately forced Hasina out. The student protesters who rooted for him can be expected to be impatient for him to deliver quickly — however, many of the issues underlying the protests are too complicated for quickfixes.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05