It’s clear that El Niño is now emerging as a major economic as well as political risk in India, ahead of national elections scheduled in April-May 2024.

The effects of the abnormal warming of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean waters towards Ecuador and Peru – generally known to suppress rain in India – are already beginning to be felt.

August so far has seen the country as a whole register 30.7% below-normal (i.e. the historical long-period average for a given interval) rainfall. As a result, the overall 4.2% surplus during the first two months of the southwest monsoon season (June-September) has turned into a cumulative 7.6% deficit as of August 27.

The India Meteorological Department anticipates no significant monsoon revival during the next five days, putting this month on course to end up as the driest ever August – even surpassing that of 1965 and 1920.

Why things can worsen

In July, the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) – which measures the average sea surface temperature deviation from the normal in the east-central equatorial Pacific region – touched 1 degree Celsius. This was twice the El Niño threshold of 0.5 degrees.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has predicted a 66% probability of the ONI exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius during October-December and a 75% chance of it remaining above 1 degree in January-March 2024. El Niño is, thus, projected to not only persist, but strengthen through the 2023-24 winter.

That, in a worst-case scenario, could lead to an intensification of the current dry conditions in September (when the southwest monsoon season ends) and beyond. It would also mean subpar rainfall during the northeast monsoon (October-December) and winter (January-February) seasons.

What that can do

Story continues below this ad

The southwest monsoon rain is crucial for not just the kharif season crops, mostly sown in June-July and harvested over September-October. It is required also to fill up dam reservoirs and recharge groundwater tables that, in turn, provide water for the crops cultivated during the rabi (winter-spring) season.

The rabi crops are mainly wheat, mustard, chana (chickpea), masur (red lentil), matar (field pea), barley, potato, onion, garlic, jeera (cumin), dhaniya (coriander) and saunf (fennel). They also include maize grown in Bihar and rice in West Bengal, Assam, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

Chart 1.

Chart 1.

The chart above shows water levels in 146 major reservoirs as on August 24 to be 21.4% lower than a year ago and 6.1% below the last 10 years average for this date. The area sown under most kharif crops this time, barring pulses such as arhar (pigeon pea) and urad (black gram), has been higher compared to last year, thanks to the 12.6% rainfall surplus in July that made up for the monsoon’s late onset and 10.1% deficit in June.

The dry weather in August can affect yields of the already-planted crops now in vegetative growth stage. But farmers may still be able to salvage these with one more shower or even the available moisture. The real issue would be not with the kharif, but the upcoming rabi season crops that are largely dependent on water in the underground aquifers and reservoirs. That’s where El Niño’s impact might be most felt.

The economic risk…

Story continues below this ad

Reservoir water levels are precarious in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha and much of southern and eastern India, which have also recorded substantially below-average/deficient rain.

In the ordinary course, these wouldn’t matter beyond a point. But with rice and wheat stocks in government warehouses at 65.5 million tonnes (mt) on August 1, a six-year-low for this date, and retail food inflation in July at 11.5% year-on-year, there is cause for worry.

For policymakers, food inflation isn’t much of concern so long as it is transitory or limited to, say, tomatoes or vegetables suffering temporary supply disruptions and likely to self-correct with the new crop’s arrivals. The problem is when inflation becomes persistent and broad-based.

Last year, public wheat stocks fell to their lowest since 2008, but there was enough of rice to keep the overall cereals inflation in check. The scenario is different today, when there’s pressure on both rice and wheat stocks, besides El Niño whose effects are still unfolding. Wholesale prices of chana have risen by near a fifth in the past one month, not due to low stocks with government agencies, but because inflation in arhar and other pulses is rubbing off on it. When scarcity in one vegetable or dal starts influencing the prices of others, it’s then that the threat of generalised food inflation arises.

…and the political

Story continues below this ad

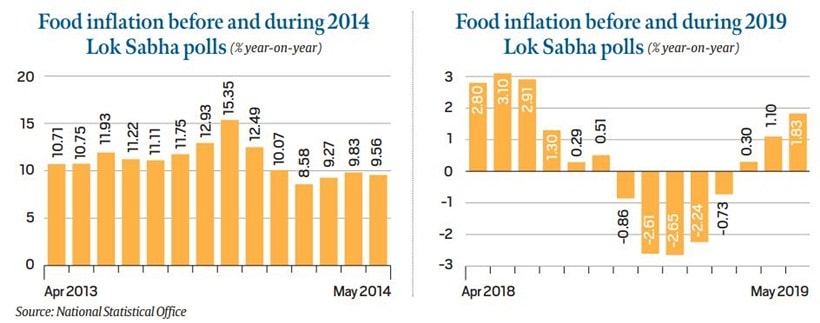

The accompanying charts show consumer food price inflation rates for two periods – the 12 months leading to the Lok Sabha elections of April-May 2014 and that of April-May 2019. The annual retail food price increase averaged 11.1% in the former period and a mere 0.4% in the latter.

Chart 2.

Chart 2.

While not the only factor, the difference between the two numbers wouldn’t have played a small part in the then ruling United Progressive Alliance’s massive defeat in 2014 and the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party’s spectacular return to power in 2019. Relatively benign food inflation and free grain rations – 10 kg per person per month – also helped the BJP in the February-March 2022 Uttar Pradesh assembly polls.

The implications of the above cannot be lost on the Modi government. Consider the various “supply-side” actions it has taken since May 2022, roughly the time when food inflationary pressures began building up:

* On May 13, 2022, exports of wheat banned.

* On May 24, 2022, sugar exports moved from “free” to “restricted” category. Total shipments capped at 11.2 mt in 2021-22 (October-September) and 6.1 mt in 2022-23 sugar years. No exports taken place after May 2023.

Story continues below this ad

* On September 8, 2022, exports of broken rice prohibited and 20% duty levied on shipments of other white (non-parboiled) non-basmati grain. On July 20, 2023, ban extended to exports of all non-parboiled non-basmati rice. On August 25, 2023, 20% duty imposed on exports of parboiled non-basmati rice. Minimum price of $1,200 per tonne, below which exports wouldn’t be allowed, made applicable for basmati shipments.

* On June 2, 2023, stock limits put on arhar and urad, with wholesale traders, big retailers, small stores and dal millers not permitted to hold more than stipulated quantities. Earlier, on March 3, import duty on whole arhar cut from 10% to nil.

* On June 12, 2023, stockholding limits imposed on wheat.

* On August 19, 2023, 40% duty slapped on exports of onion.

As El Niño bites and the 2024 Lok Sabha elections near, one can expect more such measures – to improve domestic availability and “prevent hoarding and unscrupulous speculation” – from the Modi government. That many of these go against the letter and spirit of the farm reform laws it enacted (subsequently repealed) barely three years ago is another thing.

Chart 1.

Chart 1. Chart 2.

Chart 2.