The world over, policymakers and economy analysts are waiting nervously for newly inaugurated US President Donald Trump to announce tariffs against some or many countries. The expectation has been built in because during his election campaign, Trump had said that “tariff” is his “favourite word in the dictionary” and that he would use tariffs to boost domestic manufacturing in the US. In particular, he intends to target countries with whom the US has deep trade relations such as China, Mexico and Canada. As things stand, Trump has held off unveiling any specific tariffs. Instead, he has ordered his team to study how China reacted to the tariffs Trump imposed during his first term.

What are tariffs?

A tariff is essentially a tax that a government imposes on goods that are being imported into the country in question (the US in this case).

Imagine a scenario where domestic US car manufacturers sell a car for $120 and Chinese cars are imported and sold for $100. It is quite likely that overtime, Chinese car imports rise as US consumers prefer to buy the cheaper car. This has three broad implications.

One, the US domestic car manufacturing firms lose out because of low sales. Their workers either get laid off, or at the very least, get poor salary increments. Moreover, few new jobs will be created.

Two, US trade deficit balloons. A trade deficit is the difference between the value of imports and exports, and it essentially means money flowing out of the country.

Three, consumers are getting cheaper cars.

Why impose tariffs?

Now imagine what would happen if the US was to impose a tariff of 50% on all Chinese car imports. The US government may decide to do so for one or more of the following three reasons:

Story continues below this ad

- Protect US domestic car industry: After tariffs, the Chinese car would now cost $150 and as such will be costlier than the US car ($120). Arguably, the demand will shift to US car makers and the whole industry will be better off financially.

- Raise government tax revenues: The US government may decide to raise some money by taxing a product that seems to be selling well. It is possible that if earning more revenues is the only concern, the tariff rate may not be 50%, instead much lower, say 5% or 10%, so that Chinese cars sales don’t completely dry up.

- Force the Chinese car manufacturers to set up a factory inside the US: This is called Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and it is a good way to ensure that domestic consumers get better or cheaper cars without domestic workers losing out jobs.

How are tariffs retaliated?

The country on whom tariffs are imposed (China in this example) has several options on how to retaliate.

- Dumping: China can choose to absorb the tariff and sell the cars for $100 instead of $150. They may choose to do this in the hope that overtime they would be able to drive the US car makers out of the market, and once they have achieved monopoly in the market, they can raise prices and recover all losses.

- Pass on the tariff costs to consumers: The most likely action, however, is that Chinese firms will just add the 50% tariff ($50 in this case) to the price of the car. In this case, it is the US domestic consumer who will end up paying the tariff. In turn, this will raise prices and lead to inflation in the US while the Chinese remain largely unaffected. There is another perverse outcome in such cases: The domestic car makers may also raise the prices from $120 to $140 (still below $150 of the Chinese cars). This way US car makers will be able to earn more without necessarily having to improve the quality of the car or by improving efficiency of manufacturing a car etc. They enjoy a bonus just because the US government has put “protectionist” tariffs. The government will also earn more revenues in this case. However, the US consumers will bear the cost.

- China sets up a car factory inside the US: This is essentially what Trump wants more than anything else. However, China may decide not to do so partly because it may find that it cannot produce a car for $100 in the US; this may happen because labour costs in the US (or other input costs) may be much higher than China. Moreover, shifting the factory from China to the US also implies job losses inside China.

- Trade rerouting: China may decide to re-route their cars via countries such as Mexico and Canada that enjoy a “free-trade agreement (or FTA)” with the US. In this case, China exports an almost fully made car to Mexico, where it is repackaged and sold as a Mexican export to the US.

- Trade war: China could retaliate by imposing tariffs on goods that it imports from the US, say corn or aircrafts. There is another way in which China can negate the tariffs: It can devalue its currency in such a manner that the net effect of tariffs is zero. It is important to remember that there are many currencies whose exchange rate is not fully determined by the market forces; this list includes Indian Rupee and the Chinese Renminbi.

In reality, the response is a mix of these strategies. But the important thing to remember is that almost always, tariffs hurt domestic consumers while attempting to favour domestic producers and government finances. A wholesale trade disruption could raise prices, and inflation, without even achieving the original goals of protecting domestic industry. It is also important to remember that even when domestic industry is protected, the cost — in terms of plying sub-standard and costlier cars as Indians did before the economic reforms of 1991 — is borne by the domestic consumer.

Did Trump’s tariffs against China work in the past?

They did and did not, depending on what parameter one chooses to quote.

Here’s how.

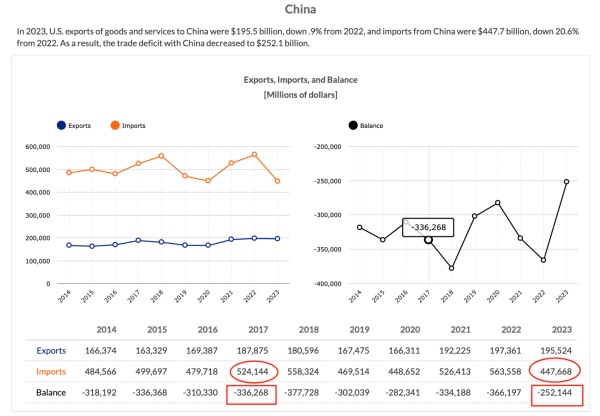

If one looks at just the US-China direct trade then the Trump tariffs against China worked very well. Look at Chart 1 that details US trade with China.

Story continues below this ad

Chart 1

Chart 1

Between 2017 (the year before Trump tariffs) and 2023, imports from China have fallen and the overall trade “balance” (or deficit in this case, as represented by a minus sign) has reduced.

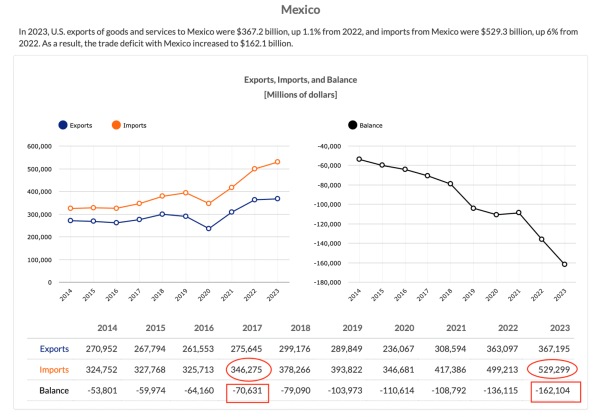

But if one looks at US trade with some of the other countries such as Mexico and Canada, a completely different story comes out.

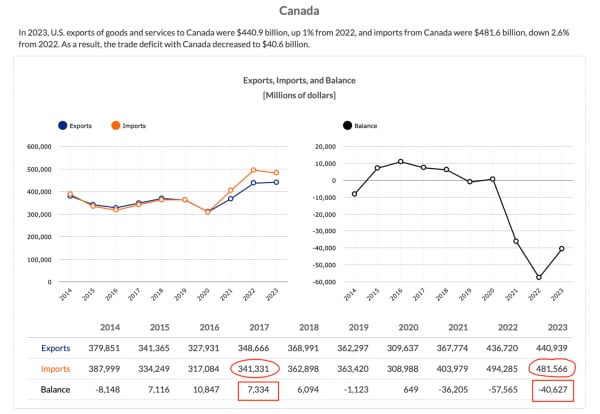

Chart 2 is US trade with Mexico and Chart 3 is US trade with Canada. These charts are sourced from the Bureau of Economic Analysis in the US Department of Commerce.

Chart 2

Chart 2

In the case of both Mexico and Canada, imports have ballooned and so has the trade deficit.

Story continues below this ad

Chart 3

Chart 3

Ajay Srivastava, a former member of the Indian Trade Service, and currently the head (and founder) of Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) says, while US imports from China declined by $81.56 billion between 2017 and 2023, the overall US trade deficit (across all trading partners) widened as imports shifted to non-Chinese sources, bypassing tariffs through free trade agreements.

“China showcased remarkable resilience, increasing its global exports by $1.1 trillion and cementing its role as a critical player in global supply chains for electronics, pharmaceuticals, and renewable energy,” he writes in a recent research report. Contrast that to the US trade deficit, which ballooned from $516 billion in 2017 to $784 billion in 2023.

According to his study, key beneficiaries of the trade war included Mexico, Canada, and ASEAN nations, which collectively accounted for 57% of the growth in US imports.

The big worry for India is: Are Indian exporters ready and capable to make use of the opportunity when a new trade war happens or will India become one of those markets that is used to pass through Chinese goods to the US, without much value-addition at the domestic level?

Story continues below this ad

Share your views and queries on udit.misra@expressindia.com

Take care,

Udit

Chart 1

Chart 1 Chart 2

Chart 2 Chart 3

Chart 3