Udit Misra is Senior Associate Editor. Follow him on Twitter @ieuditmisra ... Read More

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

Indians, in their personal capacity, are not spending enough. This component is a major engine of GDP growth. (Express photo by Sankhadeep Banerjee)

Indians, in their personal capacity, are not spending enough. This component is a major engine of GDP growth. (Express photo by Sankhadeep Banerjee)Dear Readers,

On Saturday (February 1), Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will present the Union Budget for the upcoming financial year (2025-26). The Budget is being presented at a time when the Indian economy is facing several challenges.

By itself, this is not a new scenario for the Finance Minister. Looking back at her stint as the FM (which started in 2019), one can spot several years when her Budget was almost immediately upended by global as well as domestic factors. For instance, in 2020, soon after the Union Budget, the Covid-19 pandemic led to prolonged nationwide lockdowns and resulted in India going into a technical recession.

In 2021, the Budget was followed by the most vicious Covid wave that actually led to a large number of deaths. In 2022, soon after the Budget was presented, Russia invaded Ukraine and upset the global economy by leading to a spike in inflation. In fact, even the full budget for the current financial year that was presented in July last year was seen as a quick reaction to the underwhelming political results for the ruling BJP in the Lok Sabha polls.

This time the challenges are more economic in nature. Overall GDP growth rate seems to be reverting back to the sluggish pace it had before Covid; India grew at less than 4% in 2019-20. Since then India’s GDP has registered an annual average growth rate (compounded annual growth rate) of less than 5%.

The two biggest engines of GDP growth seem to have run out of steam: Indians (in their personal capacity) are not spending enough on goods and services, and this dullness has meant that the private firms have been sitting on the sidelines instead of investing in creating new productive capacities. In sunnier times, trade (read exports) used to be a way to generate economic growth but with Donald Trump as the US President all bets are off and no one can be certain about trade prospects in the coming days, thanks to Trump’s threat to impose tariffs and possibly lead to a global trade and currency war.

That leaves the government with the onerous job of single-handedly kick-starting the economy by spending more. To a great extent, it has been attempting to do it for the past few years with little success in reviving a durable growth momentum. As a result, the government’s finances are already stretched — read, it is already under pressure to reduce its annual borrowings and pare down its existing mountain of debt.

What’s the solution? It all comes back to the Indian consumer. Unless people start spending more, it may not be possible to get out of the rut of sluggish growth. To be sure, 5%-6% annual GDP growth rate is not a pace that policymakers can be proud of; the hope is to push it closer to 7%-8% on a consistent basis, if not higher.

Given that there are limits to how much can the government spend and how much can the economy absorb such spending in the short term — say, increased spending on even more physical infrastructure (roads, railways, ports etc.) — many argue it is time to cut taxes. Doing so will leave consumers with more in their pockets and will, hopefully, trigger a spending cycle that will, in turn, incentivise firms to start investing, thus creating more and better paying jobs that further lead to a new round of spending, so on and so forth.

There is another reason why many people — especially those who are categorised as “middle class” — demand a cut in taxes: There is a growing sense that the Indian government has been over-taxing its citizens. But is that so? Of course, taxation varies from person to person depending on income and spending patterns but here are five charts that help provide some context. All data and charts sourced from Our World in Data.

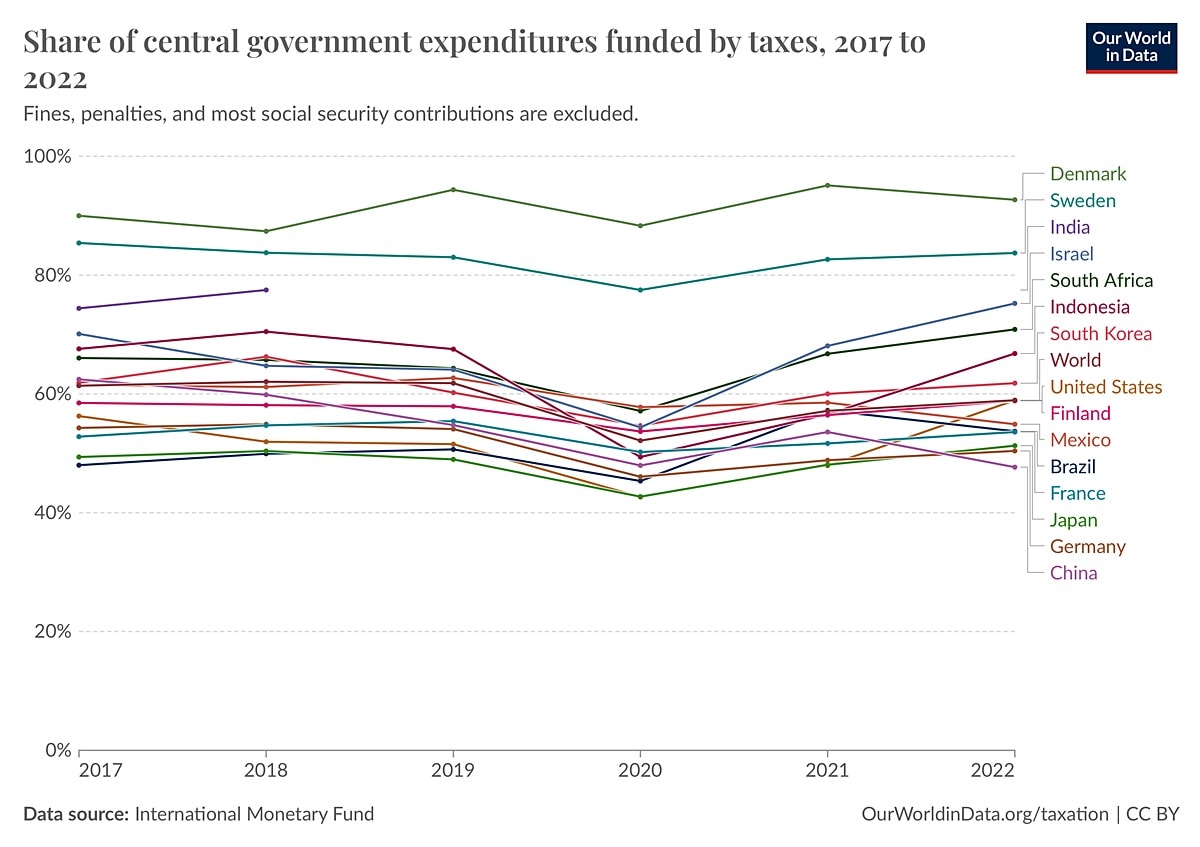

First of all, CHART 1 explains the critical importance of tax revenues for the Indian government. It maps the share of central government expenditures funded by taxes.

CHART 1.

CHART 1.

Look at the list of countries on the right. At close to 80%, the Indian central government has a very high dependence on tax revenues. Many other comparable economies such as Brazil, Mexico and China are much less dependent on tax revenues. Cutting tax rates or collecting less taxes will force the Indian government to borrow more money from the market, thus competing with private firms for investible funds, and, in the process, driving up interest rates for everyone in the economy.

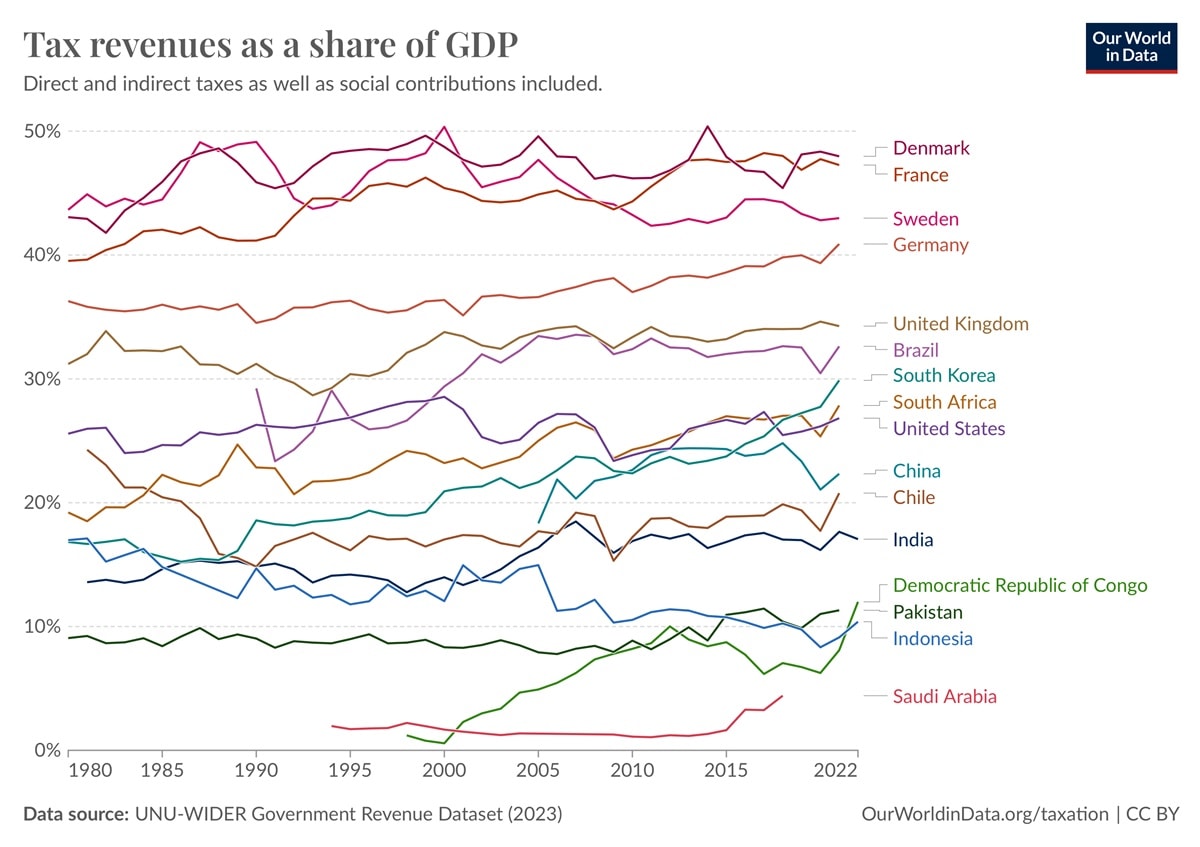

However, as CHART 2 bears out, when it comes to the total tax revenues as a share of total national GDP is concerned, India ranks fairly low; well below 20%.

CHART 2.

CHART 2.

Most developed countries in Europe manage to raise much higher levels of revenues as a proportion of GDP. This suggests that those countries are more efficient at raising revenues and that India’s government, despite being desperately dependent on taxation for their expenditure, isn’t able to target as wide a tax base.

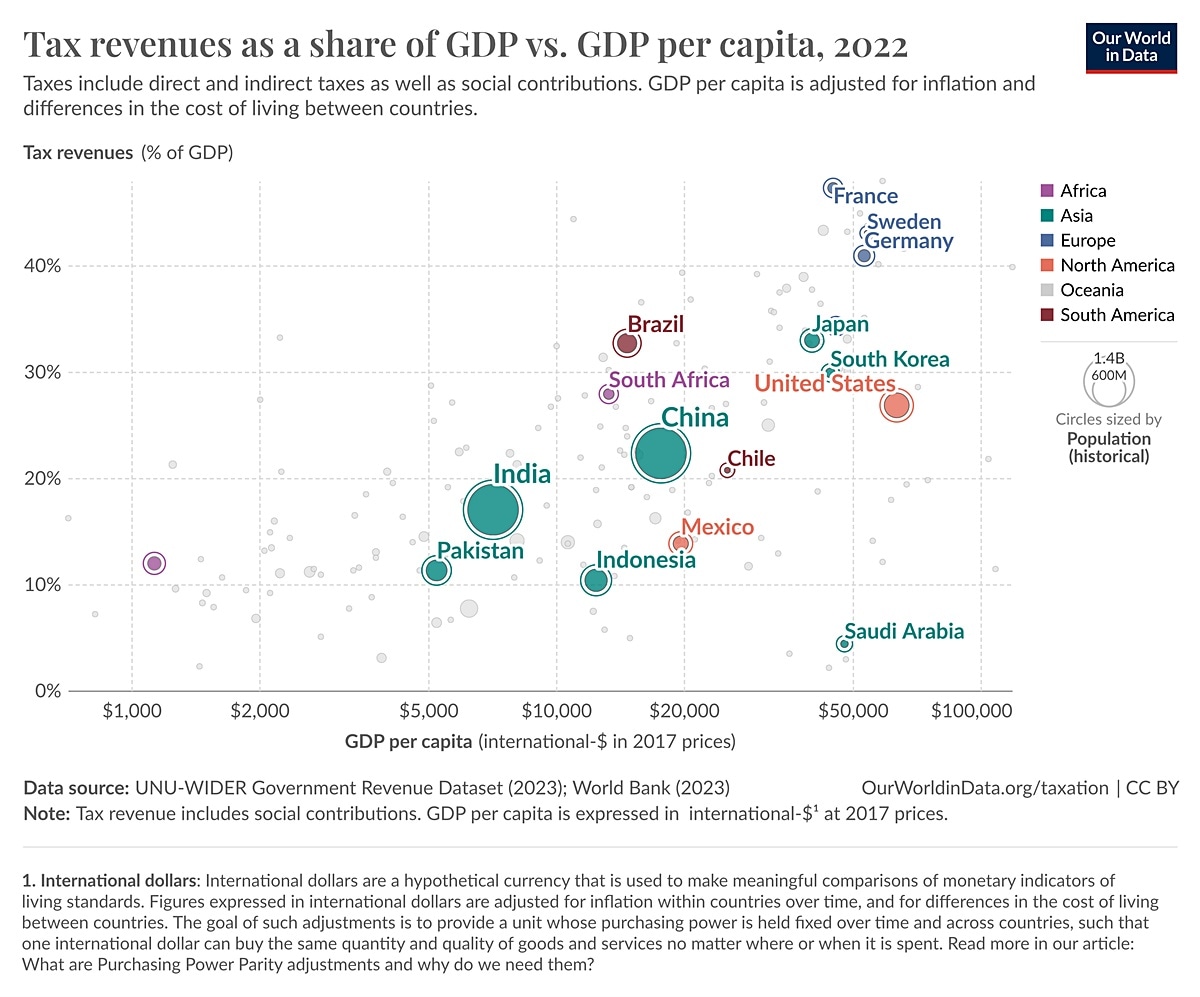

Of course, India is much poorer than the developed countries. It is here that CHART 3 helps place India in the global context. It maps tax revenues as a share of GDP versus GDP per capita. In other words, it tries to understand where India stands in terms of raising taxes (as a percentage of GDP) relative to its average income levels.

CHART 3.

CHART 3.

What CHART 3 shows is that India fits into a broad pattern where the richer a country, the more capable its government is in raising taxes as a percentage of the overall GDP. So India is behind China, which, in turn, is behind the US. Of course, there are variations. For instance, France and Germany raise much higher tax revenues (as a percentage of GDP) than Saudi Arabia or even South Korea despite being roughly at a similar level of per capita income.

This suggests that older, more established economies are more efficient in raising revenues. It is noteworthy that India raises a higher proportion of tax revenues than countries such as Mexico and Indonesia that are much richer.

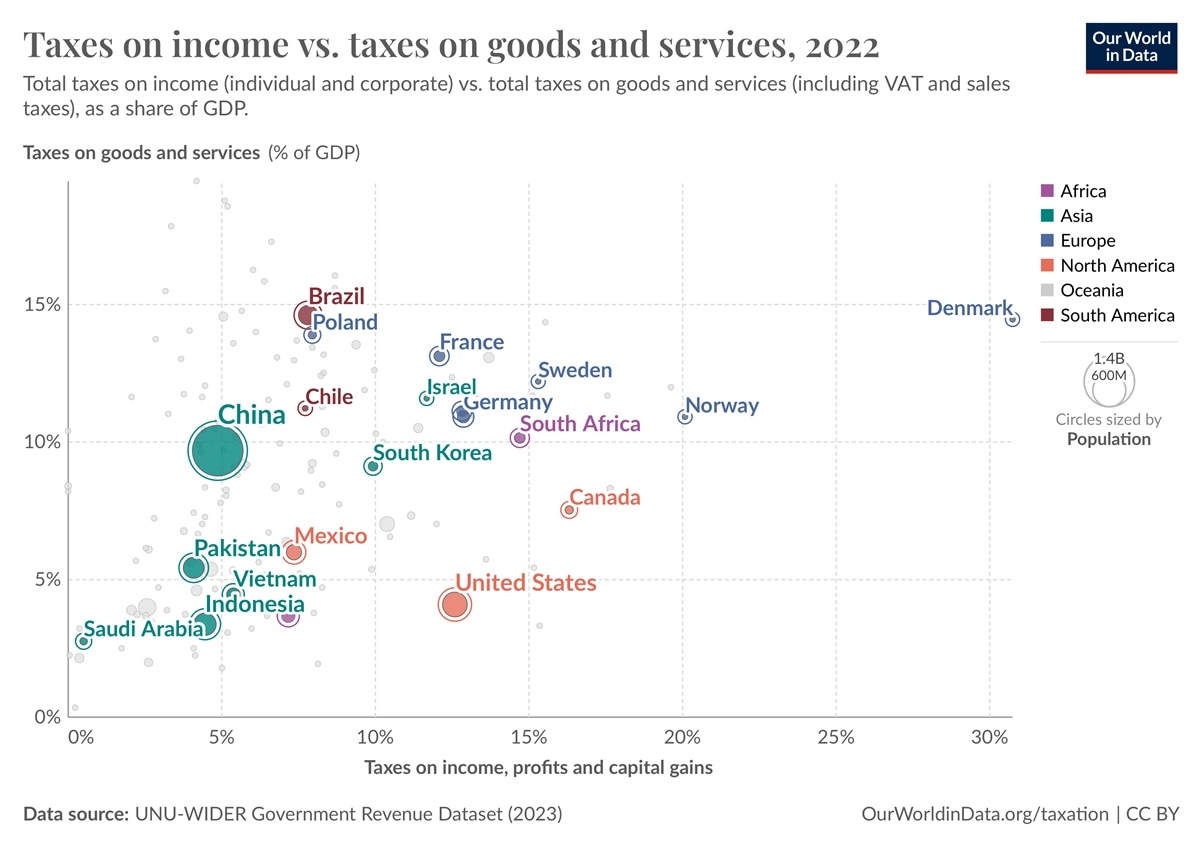

CHART 4 looks at what kind of taxes are used to bring in the revenue. This matters. Direct taxes such as personal incomes taxes are more progressive and just — that is, the rich can be made to pay a higher rate of tax as against the poor. Indirect taxes such as the GST are regressive since a poor person also pays at the same rate at which the rich pays. Unfortunately, this database did not have data for India but it is reported that in India both direct and indirect taxes roughly amount to around 7% (of the GDP) each.

CHART 4.

CHART 4.

That would make India lie fairly favourably. There are countries such as Brazil, Chile, and Poland that have much higher levels of indirect tax collections while having the same levels of direct tax collections. The CHART also shows that the real difference happens on the direct tax front where the richer developed countries use it to raise much higher levels of taxation as against emerging economies such as China or Vietnam or indeed India.

The combined reading of CHARTS 3 and 4 is that Indian taxpayers should expect higher tax collections especially from direct taxes such as personal income taxes as India becomes richer and the Indian government becomes more efficient in collecting taxes.

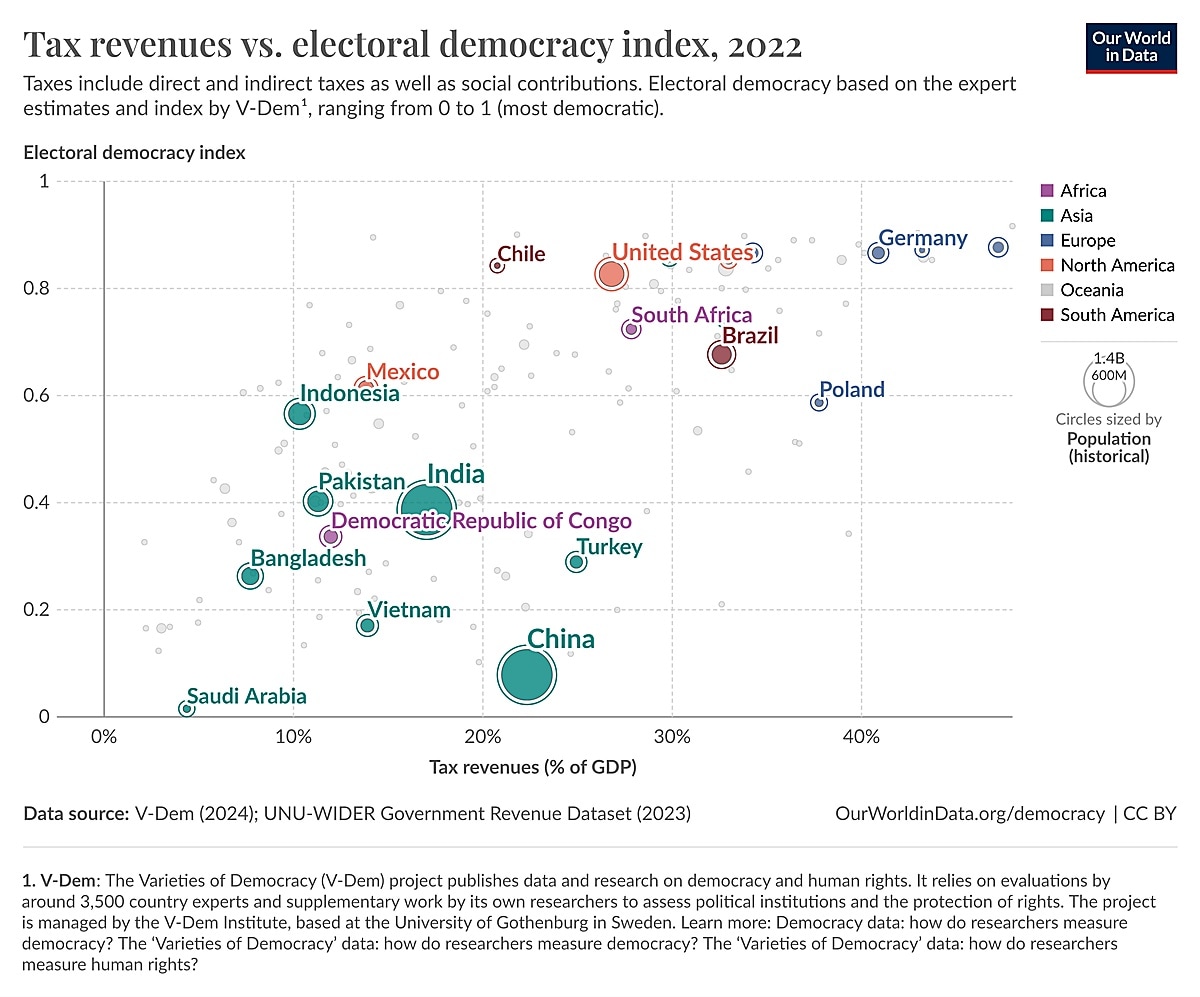

CHART 5 looks at whether electoral democracies tend to tax their citizens more.

CHART 5.

CHART 5.

As the data shows, there is a clear trend: the higher a rank for a country in electoral democracy, the more tax revenues its government is able to raise. So India does better than Bangladesh while it is behind Brazil, the US and Germany on both electoral democracy index as well as tax revenue collection (as a % of GDP). In other words, as India improves its electoral democracy ranking, expect higher tax collection.

Of course, there are countries that lie at the opposite end of the spectrum. For instance, notice how the Chinese government is able to raise a higher proportion of tax revenues than Chile despite being nowhere near in electoral rankings. Similarly, Poland manages to raise more revenues despite being at the same level on the electoral democracy index as Indonesia and Mexico.

Upshot

While it is true that, thanks to repeated economic shocks as well as the government’s inability to successfully kick-start a virtuous cycle of economic growth in the country, there are many who believe that the Indian government is overtaxing citizens.

But as the data has shown, India’s tax revenues (as a percentage of GDP) is not as high as many of the developed countries even though it funds a remarkably high proportion of central government’s spending. Moreover, as India becomes richer (in per capita income terms), and its democracy deepens, tax collection can be expected to go higher.

Should the government cut income taxes in the forthcoming Budget? Will that work in reviving the economy? Share your views and queries at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Take care,

Udit