In response, India has stated the US President’s actions are “unfair, unjustified and unreasonable”.

Experts suggest that these tariffs could result in India’s annual economic output (measured by the gross domestic product or GDP) falling by more than half a percentage point.

What is Trump’s grouse against India?

The move to slap additional tariffs seems to be driven not so much by a desire to punish India for importing energy from Russia (the formal reason), but rather as a negotiating tool to force India towards signing a trade deal that suits the US. The fact is that several other countries, such as China and the European Union, and the US continue to import goods and energy from Russia.

But more broadly, Trump has repeatedly designated India as one of the most protectionist countries in the world, or a country that had very high trade and non-trade barriers, which made it difficult for producers in other countries to sell their product in India.

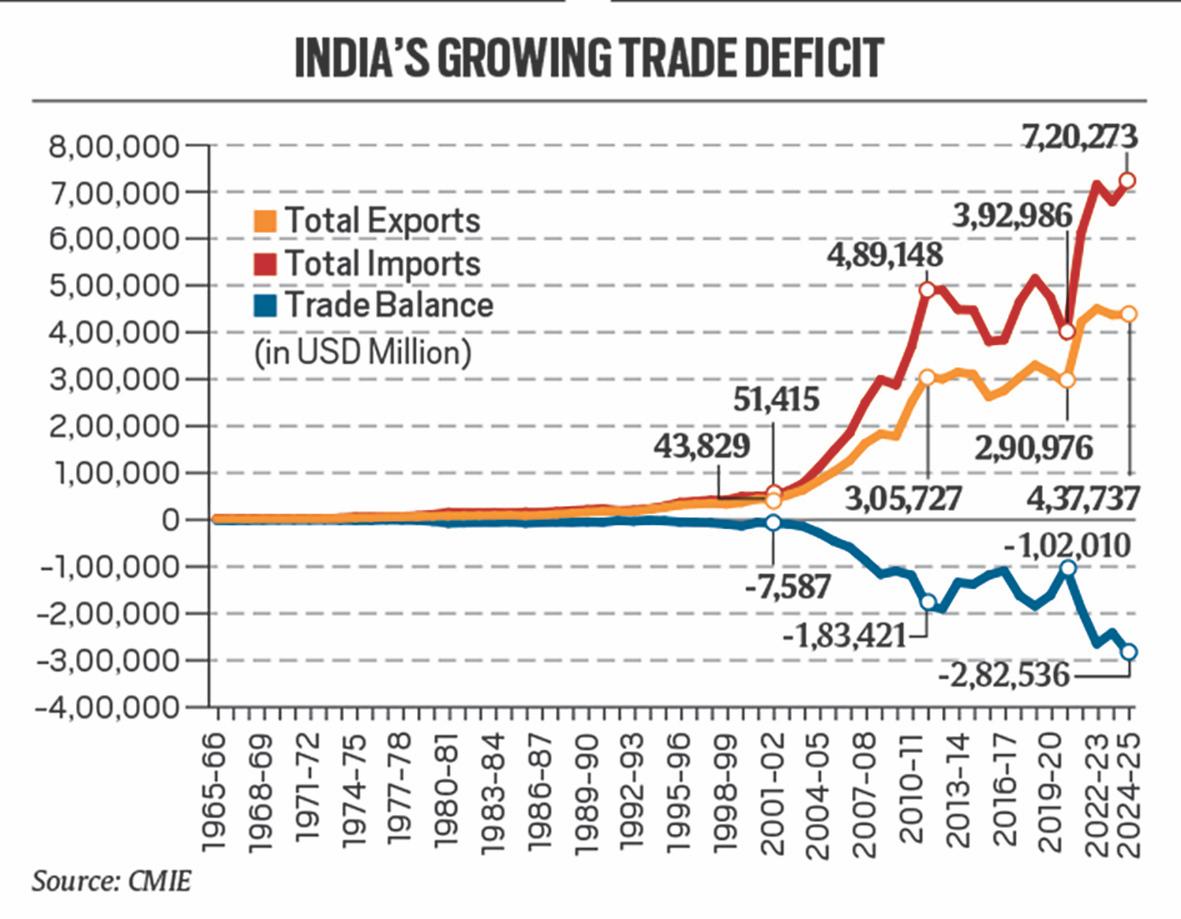

According to Trump, it is because of such barriers to entry that India enjoys a trade surplus against the US (or, put differently, the US suffers from a trade deficit with India). A trade deficit with India implies that the total value of goods imported by the US from India is larger than the total value of goods exported from the US to India.

Story continues below this ad

At the heart of Trump’s insistence on tariffs is the desire to eliminate the trade deficit and have balanced trade relations.

How will slapping on tariffs reduce the trade deficit?

A tariff is essentially a tax on domestic consumers when they import goods from outside the country. When the US slaps a tariff of 50% on imports from India, US consumers find Indian imports 50% more costly. As prices go up, the demand for such goods falls, and US consumers will stop importing from India, choosing a cheaper alternative from some other country or simply not buying that product all together.

As the imports from India fall, presuming exports to India do not change, the trade deficit will reduce and eventually close up.

Where does a trade deal figure in this picture?

Tariffs can also be used as a threat, as indeed they are being used right now, to force India to strike a trade deal and achieve the goal of eliminating the trade deficit in two other ways.

Story continues below this ad

One, is by increasing US exports to India by forcing India to open up its domestic markets to goods imported from the US. A rise in imports from the US will also bridge the trade deficit.

Two, forcing the Indian government and its associated entities to buy more goods — say defence equipment or crude oil — to close up the trade deficit.

Does that mean Trump is a champion of free-trade?

Not really.

Trump has imposed tariffs even on countries with which the US enjoyed trade surpluses such as the UK and Australia.

Story continues below this ad

The fact is that Trump believes that only balanced trade — that is, zero trade deficit — is fair trade. A trade deficit, in his worldview, implies that the other country (India, for instance) is cheating the US.

As a result, even if there was complete free trade between the US and the other countries, if the US suffers a trade deficit, Trump can be expected to slap tariffs.

What makes this ideological, albeit misplaced, stance of Trump troublesome is that no two countries naturally achieve balanced trade. More often than not, any country has trade deficits with some countries and trade surpluses with others.

Of course, what matters for any country is not to have an overall trade deficit which is unsustainable — that is, for a country to import far in excess of its ability to pay for it.

Story continues below this ad

Is Trump singling out India?

No, even though it may seem so at this moment.

Since taking over on January 20, Trump has gone after several of its closest trade and military allies — such as Canada, Mexico and the European Union — slapping or threatening to slap punitive tariffs.

Many other countries are still negotiating with the US and it is quite possible that they may see even higher tariffs being slapped on them.

Similarly, it is equally possible that Trump may hike tariff rates against India if he believes that even after these tariffs the trade deficit will not go away.

Story continues below this ad

Should India retaliate by putting tariffs on imports from the US?

No, for two reasons.

For one, a tariff essentially penalises the domestic consumer. Putting a tariff will only make it more costly for an Indian consumer to import a good from the US.

Two, placing tariffs will result in reducing India’s imports from the US, thus widening the trade deficit and triggering yet another cycle of tariffs because Trump is only looking at wiping out the trade deficit.

What will be the exact impact of US tariffs on India?

It must be remembered that while tariffs are placed by one government or one country on another, the actual trade happens not between countries but between people and companies. Putting tariffs disrupts long-established supply chains. A small scale firm or entrepreneur in Ludhiana who loses a contract for supplying, say, T-shirts to a New York store as a result of these tariffs may not recover if that business order goes to a competitor in Bangladesh.

Story continues below this ad

The exact impact will depend on how capable are Indian firms and entrepreneurs in taking a hit on their profits, and for how long, and whether there are close competitors in other countries who are in a position to take advantage (perhaps because their country is not facing as high a tariff level).

In other words, the real damage is not in terms of the loss of GDP but in terms of the loss of livelihoods and employment. Sectors such as textiles and carpets or food-related exports are heavily labour-intensive and the same half a percentage point fall in GDP in such sectors could create much deeper devastation of livelihoods.

So, what can India do?

In the absolute immediate term, Indian negotiators have to limit the damage in terms of the trade deal that is being negotiated.

But in the medium to longer term, this is yet another clarion call for domestic reforms. Policymakers and citizens alike should question: Why is it that growth in Indian manufacturing lags even Indian agriculture? Why are Indian youth unskilled despite college degrees? Why are Indian roads of poor quality? What can be done to reduce logistical costs? How can we improve the ease of doing business? Can Indian consumers get a tax break in terms of a cut in GST? Can there be a national policy on human resources to ensure India is able to leverage its young population instead of witnessing inter-state or language-based unrest?

Story continues below this ad

Trump’s reluctance to have a direct confrontation with China, which is the factory to the world, shows that when it comes to global trade, strength matters and weaknesses don’t just get exploited but also punished.

Will Indian policymakers and voters ever prioritise economic reforms over identity politics? Share your views and queries at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Take care,

Udit