In any given year, there are three main concerns for the Indian economy: Pushing up the GDP growth, maintaining price stability (read containing inflation), and reducing unemployment.

The year 2023 started on a rather nervous note on all three counts.

High inflation, in particular, was the biggest story of 2022. By the time 2023 started, inflation had started inching downwards. Although there were concerns — that higher prices had seeped through the broader economy, implying that Indian consumers will have to pay higher prices even if food and fuel prices were to come down — the focus was increasingly shifting to sustaining India’s GDP growth momentum as there was a growing realisation that high interest rates will start to drag down economic activity and worsen the already poor state of unemployment in the country.

At the global level, too, the mood was sombre. By the time 2022 ended, there was a consensus that much of the developed world will likely sink into recession. A recession is said to happen when the economic output of an economy shrinks (instead of growing) for two successive quarters (or a total of 6 months).

To be sure, while nowhere near recessionary conditions, India was facing its own challenges.

Story continues below this ad

This piece explained the contents and discontents of India’s GDP growth as it stood at the start of 2023. Simply put, private consumption expenditures, the biggest engine for India’s GDP growth (contributing almost 55% to 60% of India’s annual output), had barely grown in the three preceding years. Investment expenditures (the money spent towards creating productive capacity, and the second biggest engine of GDP growth) had grown slightly better, but most of it was just to replace the old investment. Government expenditures, the third engine, had been even more stagnant than the private first.

On unemployment, the situation had remained worrisome. Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) data revealed that the total number of employed people in India at the end of December 2022 was lower than the total number of employed people at the start of 2016.

While these may be the macro-concerns, other parameters too suggested a subdued sentiment. In the initial months of 2023, the Indian stock markets lagged most of its peers — a situation not helped by the Hindenburg Research’s report on the Adani group of companies. The general consumer sentiment, too, had been mostly negative going all the way back to 2015.

A stunning end

In sharp contrast, the Indian economy ends the calendar year on a high note. India seems to have scored a (macroeconomic) hattrick of sorts.

Consider the following:

Story continues below this ad

1. Inflation has broadly continued to trend downwards and has now come within the RBI’s comfort zone (2% to 6%). Talks of interest rate hikes and “hawkish pauses” have given way to murmurs of a sooner-than-expected cut in lending rates. This price stability has been achieved despite geopolitical tensions in West Asia.

2. Contrary to apprehensions, India’s GDP growth, instead of decelerating, has surprised on the upside. There is hardly any forecaster in town, and this includes the RBI, that has not had to hurriedly revise upwards India’s GDP estimates.

3. Official unemployment data — provided by the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) — showed that not only has India managed to reduce the unemployment rate, it has also witnessed more and more women joining the workforce.

As far as sentiments go, the stock markets have been scaling all-time highs for the past two months even as a the voters resoundingly backed PM Modi’s leadership in the recently concluded state Assembly elections.

A hattrick: How’s That?

Story continues below this ad

There are two ways to look at the Indian economy’s achievements in 2023.

If one sees the Indian economy in the context of the global economy, 2023 has the makings of the year when India started its ascent towards becoming a developed country.

While most of the developed countries are just happy to have dodged recession in 2023, India easily claimed the mantle of the world’s fastest-growing economy. In fact, a World Bank report stated that the decade between 2020 and 2030 has the makings of a lost decade for the global economy. While deceleration elsewhere makes it relatively easier for India to overtake others, it also shows that India is one of the very few countries that is expected to grow handsomely despite subdued global growth.

India’s higher inflation rate in the recent past can be summarily discounted not only for the fact that it is a growing economy and like most fast growing economies India, too, should be allowed slightly elevated inflation but also because the shocks of the past three years have spared from the ills of high (indeed, historic) inflation.

Story continues below this ad

On unemployment, too, India has shown improvement. Moreover, considering its youth bulge, the same labour force, if skilled, could easily turn out to be India’s biggest strength.

However, there is a flip side as well.

If one closely examined each of the three macroeconomic achievements, one found many points of concerns. Each of these got highlighted right through the year in different editions of ExplainSpeaking.

Let’s start with GDP growth (as it was undoubtedly the biggest achievement)

While addressing the US Congress, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated that when he first visited the US as the PM, India was the world’s 10th largest economy and eight years later it is the fifth-largest economy of the world. Further, he said that soon India will be the world’s third-largest economy.

Story continues below this ad

Obviously this is a great achievement for India and no economic growth should ever be taken for granted. Still, it is important to understand what the label of fifth-largest economy means for an average Indian.

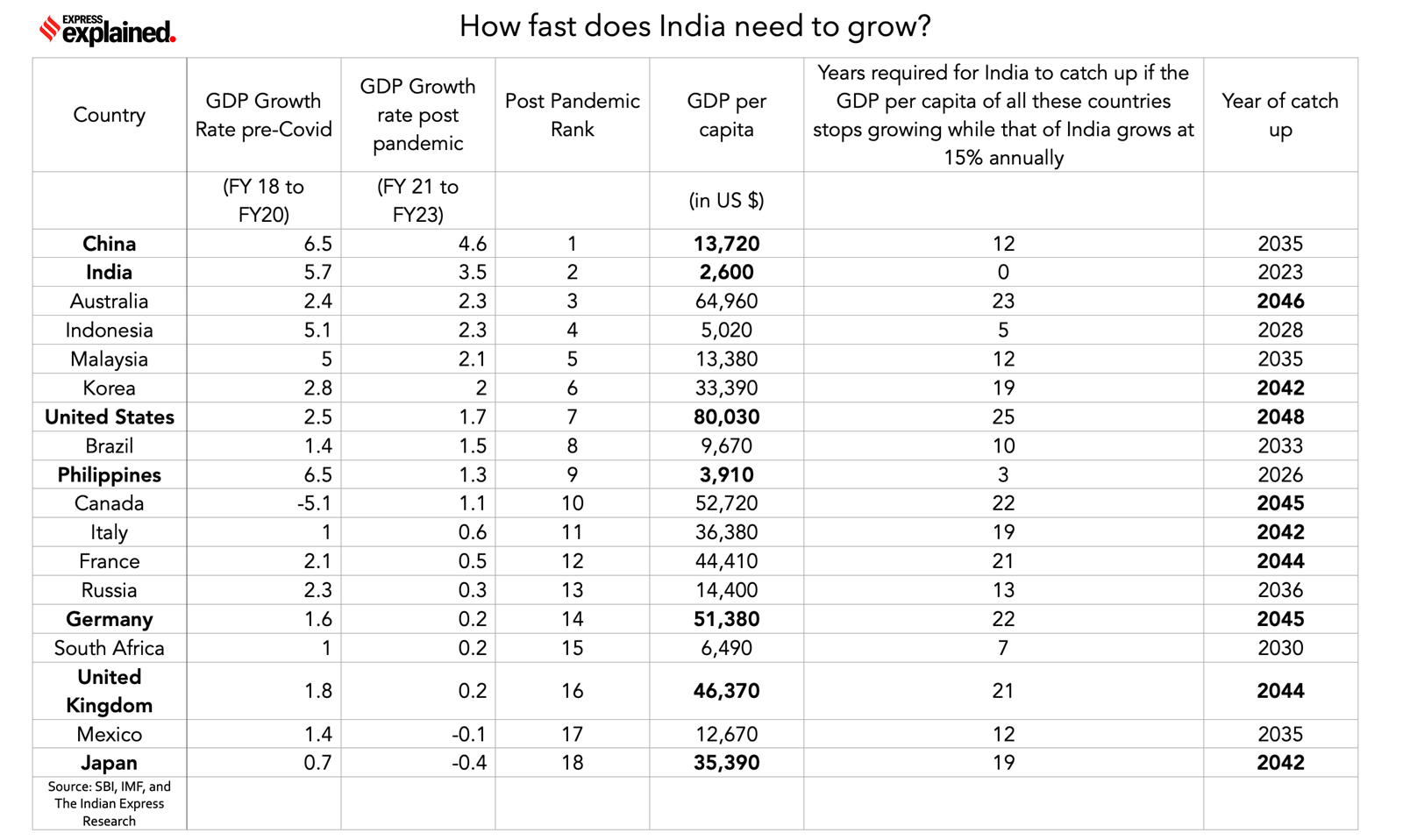

Similarly, see the TABLE below (originally carried here) to understand how far behind India is from most of its peers, and why India has no choice but to grow faster than the rest of the world.

How fast does India’s GDP need to grow compared to the rest of the world

How fast does India’s GDP need to grow compared to the rest of the world

Moreover, despite impressive headline growth, poor growth of private consumption continued to be the fly in India’s GDP ointment. An analysis of the Indian economy under the first 9 years of Modi government showed how income growth of average Indians has moderated when compared with the 10 years of UPA.

In fact, it isn’t just the average Indian who is struggling. Even the ultra rich have been leaving India in droves.

Story continues below this ad

The other problem with India’s growth is that private sector is not getting adequately enthused even now to start fresh investments across the board. Researchers at the Bank of Baroda closely followed up this issue and found some sobering findings in July. As of December, Bank of Baroda found that the K-shaped recovery in private consumption was resulting in a similar K-shaped recovery in private investments as well.

However, notwithstanding India’s growth surprise, GDP calculations have continued to attract controversy. Read this analysis of the quarterly GDP data to understand why many question the GDP data.

Lastly, there’s the introduction of a new term: The Hindutva rate of economic growth.

On unemployment

For one, even though the official PLFS data shows a better picture than the CMIE data, this is true only until one doesn’t scratch beneath the surface. As this piece explained that even though India’s official employment data shows improvement, the quality of jobs getting created is getting worse even as monthly earnings have remained largely stagnant since 2017.

Story continues below this ad

The fact is the relationship between India’s GDP growth and the generation of employment for its people has become weaker over time.

In fact, if one looks at CMIE data — which comes out each week as against PLFS which comes out with a lag of anywhere between a quarter and a year — several disconcerting trends emerge.

For instance, India is becoming a young country but with an ageing workforce. India’s workforce is becoming increasingly male-dominated. Contrary to the popular notion, the only category where Indian entrepreneurship is rising is the ‘self-employed’ one, which refers to jobs like taxi drivers, astrologers, etc., and reflects poorly on the broader economic conditions in India.

Even though the incumbent government has largely dismissed the unemployment concerns for most of its tenure, over the past year or so, one can see none other than the Prime Minister organising “Rozgar Melas”. But are these the solution to India’s labour woes? Read this.

A related topic is poverty reduction.

In his speech on Independence Day this year, PM Modi stated that in the first five-year term of his government, 13.5 crore Indians had been rescued from poverty and that they were on their way to become the middle class. But since there has been no official update to India’s poverty numbers since 2011, how was this calculated? Moreover, has the pace of poverty reduction improved over time? Read this piece to know more.

On containing inflation

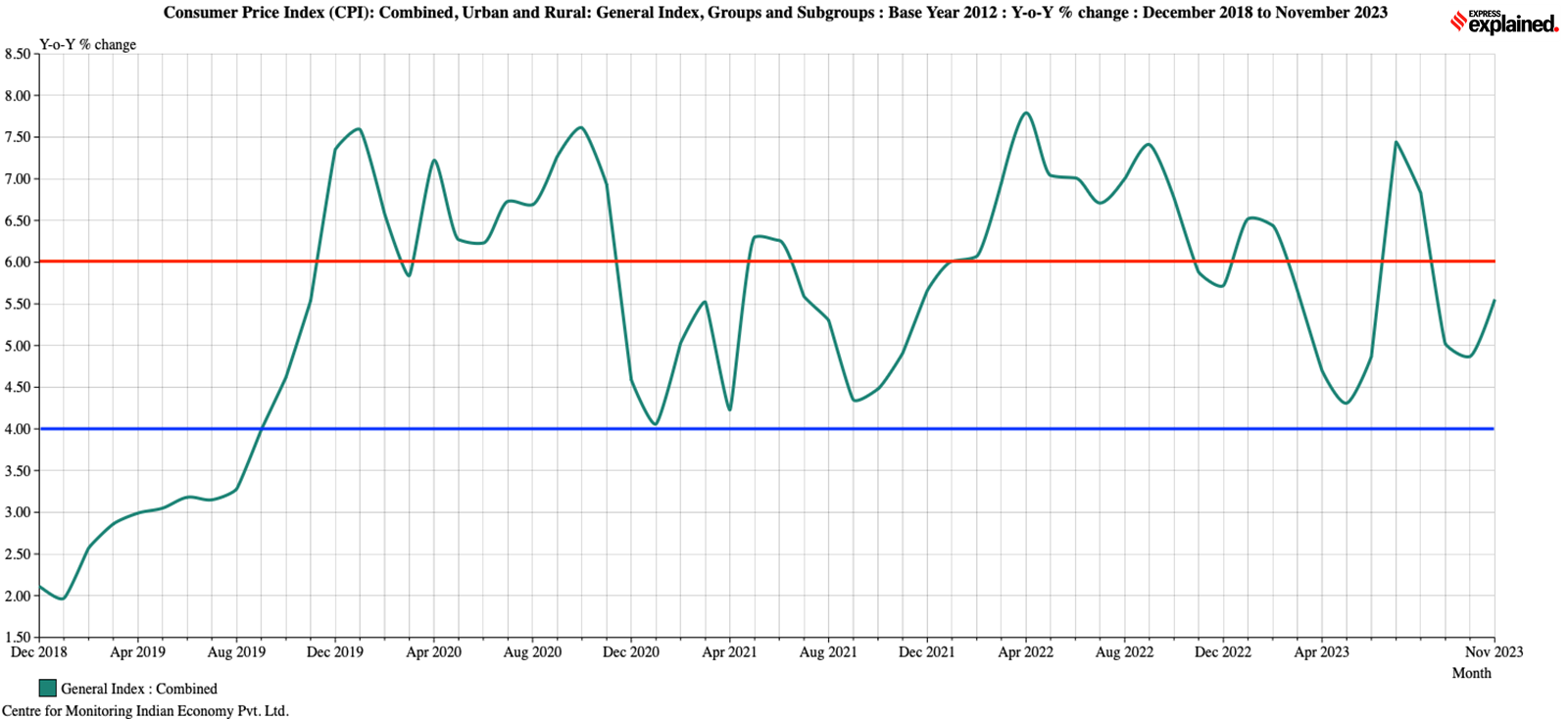

The CHART below shows the extent of India’s success in attaining price stability. The red line corresponds to the 6% upper limit of RBI’s comfort zone while the blue line corresponds to 4% — the target rate for RBI.

Chart on Consumer Price Index change over the years, from December 2018 to November 2023.

Chart on Consumer Price Index change over the years, from December 2018 to November 2023.

While inflation has come below 6% on several occasions in 2023, the fact is that consumer inflation has not once fallen to the 4%-mark since September 2019 — that’s four straight years or 48 months on the trot.

Such high levels of inflation in the preceding years resulted in some bizarre situations. For instance, in June and July this year, Tomato prices were sky-high, and yet, the inflation rate of tomatoes was negative.

Moreover, such sustained high levels of inflation not only eroded people’s purchasing power but also made many to question desirability of the inflation-targeting regime for a country like India or indeed, the efficacy of RBI itself. Interestingly, if one follows this thread, one can justifiably argue that RBI’s actions might actually be worsening inequality.

Clearly, it is easy (and to a great extent, true) to say that 2023 has been a remarkable year for the Indian economy from the point of view of macroeconomic stability. But even a gentle probe of the data throws up a far more complex picture.

ETCETERA

There were many pieces which were either about some of the less-discussed aspects of the Indian economy or about developments in other economies or indeed about some economists or some economic concept. For instance,

👉 India’s loss at the ICC Cricket World Cup led to this explanatory piece on the (non-existent) law of averages.

👉 We also asked whether Thakur should have killed Gabbar, and how that might have affected the rule of law.

👉 There was a piece on the economics of climate change in India.

👉 One on Argentina’s new president Javier Milei and dollarisation — his radical policy to save Argentina’s economy.

👉 Lastly, one on this year’s Economics Nobel to Claudia Goldin, who explained how marriage, parenthood, and the pill impact women in the workforce.

With the hope that 2024 will be an even better year than 2023, here’s wishing all readers a very happy new year!

See you in 2024, and don’t forget to grab that mask!

Udit

How fast does India’s GDP need to grow compared to the rest of the world

How fast does India’s GDP need to grow compared to the rest of the world Chart on Consumer Price Index change over the years, from December 2018 to November 2023.

Chart on Consumer Price Index change over the years, from December 2018 to November 2023.