National Mathematics Day: Remembering the legacy of Srinivasa Ramanujan

Every year, on December 22, India observes its National Mathematics Day in honour of Srinivasa Ramanujan, regarded as one of the greatest mathematicians to ever grace the planet.

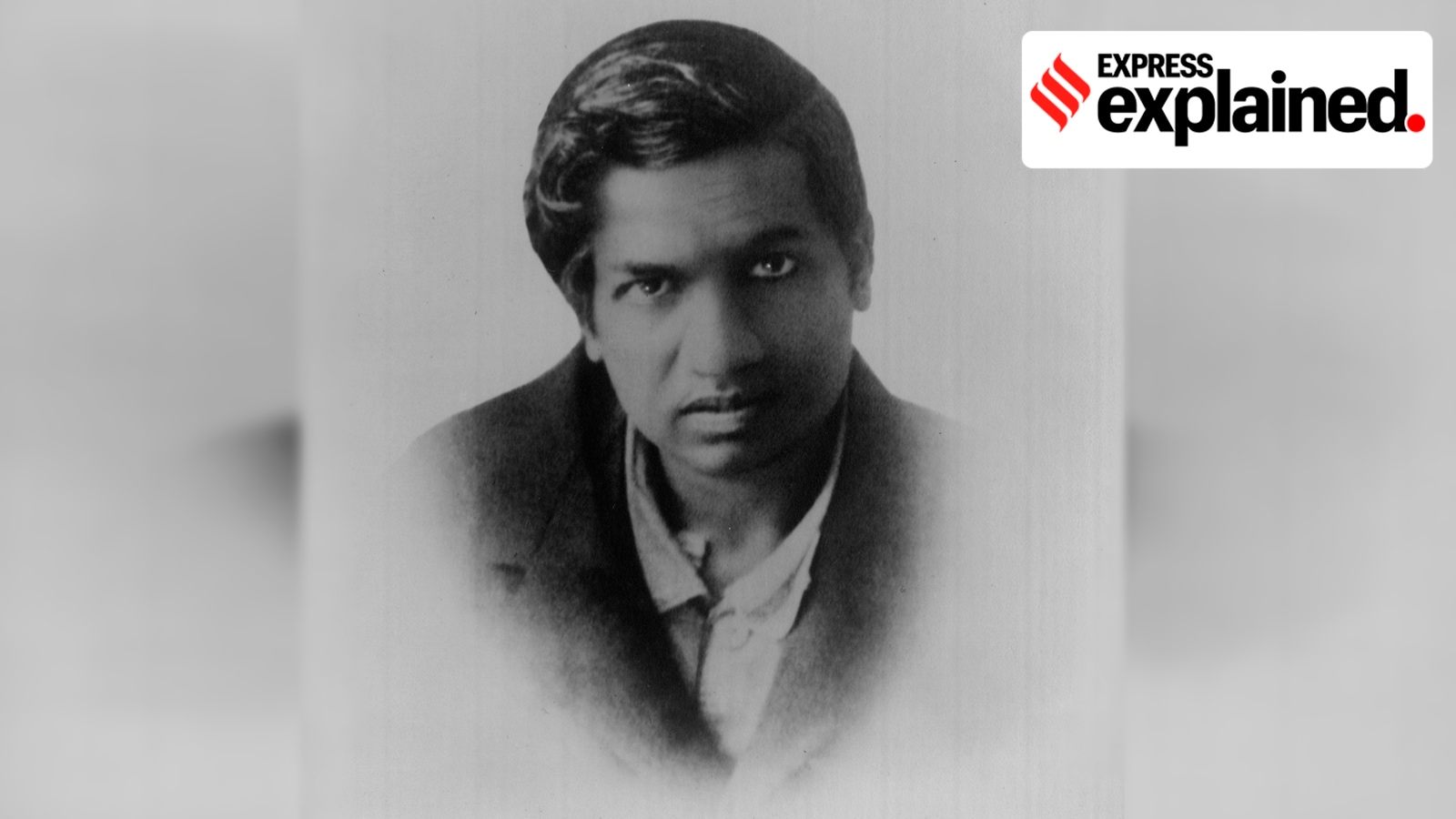

S Ramanujan was born on December 22, 1887. (Wikimedia Commons)

S Ramanujan was born on December 22, 1887. (Wikimedia Commons)December 22, the birth anniversary of legendary mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920), is celebrated as National Mathematics Day.

His time on Earth was short, and he developed many of his ideas in isolation. Nonetheless, Ramanujan left behind a legacy that continues to amaze and inspire mathematicians till date.

As his close collaborator GH Hardy once said in an interview: “[H]ad he been introduced to modern ideas and methods at sixteen instead of at twenty-six… it is not extravagant to suppose that he might have become the greatest mathematician of his time.”

Here is a brief look at the life and legacy of Srinivasa Ramanujan.

Excelled in mathematics, struggled in other subjects

Born in the town of Erode in Madras Presidency (now Tamil Nadu), Ramanujan came from humble origins. He was a sickly child, contracting — and somewhat miraculously surviving — smallpox at the age of 2. In fact, he would be plagued by ill health for the rest of his life.

But even as a child, his mathematical aptitude was apparent. By the age of 14, he was completing mathematics examinations in half the allotted time, and exploring complex topics way beyond the capability of an average 14-year old.

Born #OnThisDay in 1887 was Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. Though he had very little formal training, his work was substantial, often using methods that were completely novel. In 1918 he became one of the youngest Fellows of the Royal Society. https://t.co/XqvU8okbMK pic.twitter.com/if9Zx1JIVi

— The Royal Society (@royalsociety) December 22, 2023

In 1904, after finishing secondary school, he received a scholarship at the Government Arts College, Kumbakonam. But so engrossed in mathematics was he that he failed in most other subjects and thus lost the scholarship.

Finally, he managed to enrol at Pachaiyappa’s College in Madras (now Chennai). Here too he would excel in mathematics while struggling in other subjects. Thus, he was unable to graduate with a Fellow of Arts degree, and was left with abysmal job prospects and dire poverty, with mathematics his only refuge.

An inspired mind

By 1910, Ramanujan was gaining popularity in Madras’ mathematical circles. In 1912, V Ramaswamy Iyer, founder of the Indian Mathematical Society, helped him get a clerical position at the Madras Port Trust. For the first time, Ramanujan secured a stable income. But mathematics was still his first calling. At his office, he would quickly complete his work, and then spend his spare time doing mathematical research.

Eventually, Ramanujan began sending his work to mathematicians in Britain. His breakthrough arrived in 1913, when the Cambridge-based GH Hardy wrote back. Impressed with Ramanujan’s theorems and work related to infinite series, Hardy called him to London.

He would depart for Britain in 1914, and with Hardy’s help, got enrolled in Trinity College, Cambridge. He would spend nearly five years in Cambridge, collaborating with Hardy and JE Littlewood.

Ramanujan’s lack of formal training was made up by his intuition, and inspired thinking. As Hardy would later say: “He combined a power of generalisation, a feeling for form, and a capacity for rapid modification of his hypotheses, that were often really startling, and made him, in his own peculiar field, without a rival in his day.”

In 1917, Ramanujan was elected to be a member of the London Mathematical Society. In 1918, he also became a Fellow of the Royal Society, becoming one of the youngest to ever achieve the feat.

However, Ramanujan remained plagued with illness for much of his time in Britain. Unable to adjust to the diet and climate of the island nation, he would eventually return to India in 1919. He passed away a year later.

An enduring legacy

Ramanujan’s genius, Hardy once said, was at par with Euler and Jacobi, the greatest modern mathematical minds in the West.

American Mathematician Bruce C Berndt, best known for analysing and developing Ramanujan’s theories, wrote about how Hardy rated mathematicians. “Suppose that we rate mathematicians on the basis of pure talent on a scale from 0 to 100. Hardy gave himself a score of 25, JE Littlewood 30, David Hilbert 80 and Ramanujan 100.”

His work in number theory is especially regarded, and he made advances in the partition function. Ramanujan was recognised for his mastery of continued fractions, and had worked out the Riemann series, elliptic integrals, hypergeometric series, and the functional equations of the zeta function.

After his death, Ramanujan left behind three notebooks and some pages containing unpublished results, on which mathematicians continued to work on for many years.

In 2012, then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh declared December 22 as National Mathematics Day in honour of the great man.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05