Hardlook | ‘Namaskar, Delhi Police Control Room’

The greeting rings out when one dials 112, the emergency helpline manned by police personnel of the PCR unit. The Indian Express visits the command centre to see how they respond to distress calls 24x7 and ensure speedy action

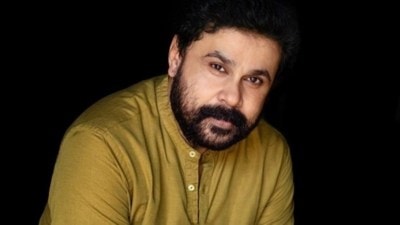

(Clockwise from above) Constable Monica Nain at the command centre; head constable Nirmala Kumar and constable Suresh, posted in the South zone. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra)

(Clockwise from above) Constable Monica Nain at the command centre; head constable Nirmala Kumar and constable Suresh, posted in the South zone. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra) “Namaskar, Delhi Police Control Room… bataiye kya hua?” Constable Monica Nain answers the telephone while focusing on two computer screens in front of her. The caller, a senior citizen, alleges he had been beaten and robbed of Rs 3,000 by unknown assailants in Mandoli.

To quickly get more information from the seemingly frightened caller, Nain asks in a calm tone: “Maar peet kari hai aapke saath?… Kaise cheene aapke paise?… Gaadi rukvayi aur paise cheen ke bhag gaye?” The call abruptly disconnects. Nain patiently waits for him to call back, which he does after two minutes. She goes on to ask, “Haan sir, bataiye voh log kis taraf bhage? Kya voh paidal the? Aap abhi thik hai?”

As the man narrates his ordeal, providing her with minute details, Nain assures him of quick police action even as she quickly fills up his basic details and incident description onto her system. Another monitor pinpoints the caller’s location and nearby landmarks to transfer it to the dispatch centre, which further sends a PCR vehicle to the spot.

Nain is among the 40-odd personnel at the Delhi Police’s PCR command and dispatch centre in Shalimar Bagh who man the emergency helpline number or Emergency Response Support System (ERSS) — 112 — and assist a steady stream of distressed callers in the capital.

Catching a breather between calls, Nain, who has been posted with the PCR unit for four years, says, “Be it a murder, a rape or a case of domestic abuse, we have to quickly cater to all calls within 5-10 minutes and send information to the dispatch centre for speedy redressal… The first call of the day is as important as the last one and the more information we can get from the caller, the better it is for us to understand the severity of the situation.”

Since her shift started at 2 pm, she has handled at least 20 calls. A minute later, among other buzzing telephones inside the control centre, Nain’s phone rings again. The caller asks for the number of the traffic control room. Nain quickly whips out a file from under the monitors and provides the caller with the traffic helpline. “Sir koi aur help chahiye aapko?” she politely asks, to which the caller replies in the negative.

The constable says being calm and composed while listening to a distress call is a skill she has mastered over the years: “Often it becomes very difficult to handle calls where people become aggressive and refuse to listen to us, thus giving incomplete details about the incident… the key is to convince the caller that we are here to help them.”

In calls claiming sexual assault, Nain says the first step is to console the victim and make them feel they are in a safe space. “Calls pertaining to domestic abuse also need to be dealt with carefully… I received one such call a few days ago; the woman was scared and it took me around 10 minutes to calm her down before she gradually opened up to me.”

Persuasion and keeping the caller engaged during the conversation are also skills that PCR call takers need to polish over the years, especially in suicide calls. Recalling another call from last week from a man threatening to commit suicide, Nain says in such cases, one has to don the hat of a friend. “I kept speaking to the man and had to convince him to not take such a drastic step, for it will not solve anything but cause pain to his family… Meanwhile, PCR vans were deployed after tracking his location through the Global Information System (GIS) and he was rescued from his house,” says Nain.

Keeping her emotions in check is another skill she has had to master: “In calls related to child assault, it does take an emotional toll on me when the mother or the child describe the situation… But like any police officer, we have largely become immune to such incidents.” Ten minutes later, Nain’s telephone buzzes again. She swiftly picks it up and greets the caller.

“Namaskar, Delhi Police Control Room… hello?…,” she says, before the call disconnects. It was a blank call, when there is no response from the distress caller — something that the command centre often receives. “Often children fiddle with phones and accidentally press the emergency button… We also receive several prank calls from drunk persons dialing 112 for fun…,” says Nain.

The working

In 2019, the Delhi Police launched the single emergency helpline 112 for immediate assistance. This replaced the previous response system where one had to dial 100 for police, 108 for ambulance services and 101 for fire assistance.

Once a caller dials 112, he or she is directed to the Delhi Police’s Interactive Voice Response System, following which the caller has to press 8 for further assistance, be it for seeking an ambulance, fire or police services. Depending on the grievance, the call is accordingly diverted to the agency concerned.

At the PCR command and dispatch centre, over 135 personnel, majority of them women, work 24×7 in four shifts. An automatic call distribution system helps route the calls to less busy personnel. Crime calls are directed from the command to the dispatch centre, where around 35 personnel coordinate with the nearest PCR vehicle, police station concerned as well as the district for quick deployment of assistance.

Officers said heinous offences like murder and sexual assault are immediately marked high-priority when sent to the dispatch centre and senior officials are informed. Currently, 750 PCR vehicles are distributed across 15 zones or districts. Each zone has at least 40 PCR vans at a time, while over 5,000 police personnel are attached to the unit.

Around 50 all-women PCR vans are also deployed across the city. Vehicles attached with police include Prakhar anti-street crime vans and anti-terror Parakram vans.

In September 2020, after years of functioning as a separate unit, former Delhi Police Commissioner Rakesh Asthana had merged the PCR unit with the district police, making SHOs of police stations the controlling authority of PCR vans. While the move was aimed at ensuring better emergency call management and increased assistance from police stations, it led to longer response time and increase in workload from districts rather than for PCR.

Following backlash for alleged lapses of the unit in the Sultanpuri hit-and-run case, where a 20-year-old woman, Anjali, was killed after being hit and dragged for 10 km by a car on January 1, Delhi Police Commissioner Sanjay Arora in February separated the unit to make it “more transparent” and reduce response timings.

Post this, officials claimed response timings have come down to 7-8 minutes for each call from around 15 minutes earlier. A senior officer said incident reports or haalat are now sent quickly by PCR personnel on the ground to the command centre for quick action, while visibility of PCR vans has also increased.

First responders

Sitting inside their PCR van, head constable Nirmala Kumar and constable Suresh, posted in the South zone, receive a call on their phablet attached to the command room to quickly assist a 35-year-old woman being harassed by her husband. The duo rush to the spot, where the woman tells head constable Nirmala that her husband keeps harassing her and comes to her workplace to intimidate her.

When asked if she wants to file a complaint, the woman refuses and says she only requires assistance to get back home from her office. After consoling her, Nirmala makes the woman sit inside the PCR van and drops her at the nearest bus stop, before sending the incident report back to the command room.

Suresh and Nirmala, both armed with a pistol, have responded to three calls since morning — a quarrel, a domestic assault and assisting an elderly woman. Jotting down records of all calls of the day in her register, Nirmala says, “At a crime scene, our role is as important as the investigating officer as we are often among the first to reach the spot… be it in helping shift bodies to the nearest hospital, comforting grieving family members or navigating narrow lanes by foot in areas where PCR vans can’t enter.”

Handling mob situations are among the toughest jobs faced by PCR personnel, adds constable Suresh. “We have to simultaneously control the mob while keeping the general public out of harm’s way. Even our vehicles are attacked… assistance from the local police station is often taken in such situations.”

“Our responsibility is not only limited to quickly reaching crime scenes but also to help the public with basic facilities in times of need,” says Nirmala, as she pours cold water in a bottle for a pedestrian from a water cooler placed in the trunk of the PCR vehicle.

Back at the command room, constable Nain receives another call. Unlike the others, this one is a call of appreciation. “The caller thanked me for quickly resolving her grievance and most importantly, listening to her,” she says.