Dear Modi sarkar, Start Up India is fine, but what about rural entrepreneurship?

Youth require mentorship, guidance and a cocktail of technical, financial and soft skills, very specifically to cater to these kinds of professions – all of which remain conspicuously absent from the grand, new plan.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Finance Minister Arun Jaitley during the launch of “Startup India” action plan at Vigyan Bhawan in New Delhi. (PTI Photo by Kamal Kishore)

The NDA government, which came to power with a promise to cut red-tapism, is seeking to re-invent India’s business-friendly image, which so far places it as one of the 40 ‘least’ favorable countries in the world for starting enterprises. But even as the Startup India announcement has captured the imaginations of urban India – aspirations of rural entrepreneurship remain forgotten.

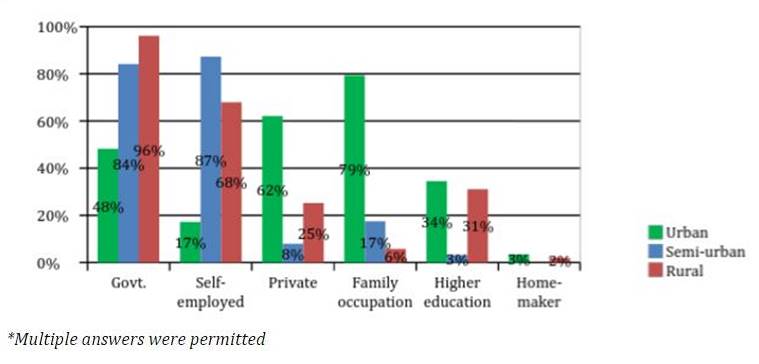

In a basic study conducted across four states, for the Niti Aayog, Pratham expectedly found that government jobs remain the holy-grail for low-income youth. In an unlikely twist, however, almost 70 per cent of the respondents from rural and semi-urban areas aspired to become ‘self-employed’ entrepreneurs, in stark contrast to their urban counterparts, for whom entrepreneurship was least aspirational.

[related-post]

At a cursory glance, these results seem counter-intuitive – why would low-income youth from rural and semi-urban areas, well-aware that small ‘shocks’ of misfortune could drive them from survival to destitution, not jump at stable jobs? The answer to why such a small percentage of rural youth aspire for formal-wage employment compared to 60 per cent of urban youth lies in between the past-experiences and present-opportunities in rural India.

Nearly all the rural workforce for generations has been engaged in only two professions – farming and casual labour — in both of which individuals largely have the freedom to choose their own schedules and methods. With little or no education, these youngsters have had fewer restrictions on their actions or time, making formal sector employment unattractive.

But more importantly, the role models for these young men and women have always been entrepreneurs – be it the ‘construction-thekedar’ (or contractor) leading a large team of labourers and making a good living, or the small shop owner who is the centerpiece of the village and the fulcrum for all activities. The most prosperous villagers, who have been able to actually live in villages, are entrepreneurs.

The organized sector exists miles away in cities and far from the imaginations of rural India. The distance from organized employment, forcing relocation from homes and families, makes it less aspirational. Additionally, the lack of awareness about opportunities available and skills required to break into these organised sector jobs makes entering this sector seemingly impractical.

Woes of migration

In another survey conducted by Pratham with the low-income youth who had migrated to urban areas in and around Mumbai, it was found that 42 per cent of all respondents who had migrated wanted to return to their villages, eventually, while another 21 per cent said they would only continue living in the city if they were able to afford relocating their families with them. Thus, it isn’t just the daunting idea of relocation that dissuades organized-aspiration, but also because of shared-experiences of migration, which aren’t always positive.

For instance, 22-year-old Rahul Dharmik, who hails from the Naxalite-torn district of Gadchiroli in Maharastra, relocated to Mumbai after completing a 2-month long vocational training course in masonry. The reason for his migration was not to escape the violence in his region, or for the charms of a city-life. Dharmik labors for 12-hours a day, in frankly terrible working conditions, so that he can learn the skills of the trade and create enough savings to start-up as a construction-contractor in his own village.

Re-imagining entrepreneurship

With the recent successes of unicorn start-ups in India, ‘entrepreneurship’ has finally become the ‘Indian Dream’ for the urban upper-class. But for 60 per cent of India’s population that lives in rural areas, entrepreneurship has always been the apex aspiration, the best case scenario to lead a good life in a village.

Yet this is also a population that received very little respite in the Jan 16 announcement which promises tax-exemptions, funding opportunities, incubation-support and fast-tracking of patents, none of which remain the core hindrances in the realization of rural entrepreneurial-aspirations.

Firstly, entrepreneurship for low-income youth means a lot more than what is covered in its conventional definition – that of being asset owners. It engulfs an entire range of ‘services’ occupations that make these youth ‘self-employed’, like electricians who service entire buildings, construction-contractors who have large teams, plumbers with government tenders, and similar professions in the semi-organized sector which rely on client payments, that are usually heavily delayed. The requirement for this segment of ‘entrepreneurs’ is not so much of capital-funding but of a ‘liquidity fund’ or ‘working-capital support’, till they are able to save enough themselves to cover for delayed payments. Additionally, barriers-to-entry like complicated registrations and lack of legal and financial guidance hinder the poor from rising to the peak of their occupational-potential, despite possessing skills and experience.

Secondly, even the promised incubation-support for asset-based entrepreneurship, typically for those associated with a post-graduate college in India and funded or recognised by a government agency, would not be equipped to cater to individuals that aim to own vegetable carts, automobile garages, salons and rickshaws. These youth require mentorship, guidance and a cocktail of technical, financial and soft skills, very specifically to cater to these kinds of professions – all of which remain conspicuously absent from the grand, new plan.

This ambitious announcement of a Rs. 10,000 crore fund for Startup India comes right after the declaration of the plan to ‘skill’ 400 million youth by 2022. Unless the two are tied together to ‘skill’ and ‘create entrepreneurs’, rural India stands to benefit little. It is the only way to make ‘skilling’ truly aspirational, and to lift the ‘glass-ceiling’ on career growth, imposed by entry-level wage employment, in professions like carpentry, construction, hospitality and beauty-servicing. Micro-Entrepreneurship is the missing link in the livelihoods chain, a level below even SMEs but with the opportunity to create a new sector entirely.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05