Bhopal gas tragedy: 30 years later we revisit the site of disaster

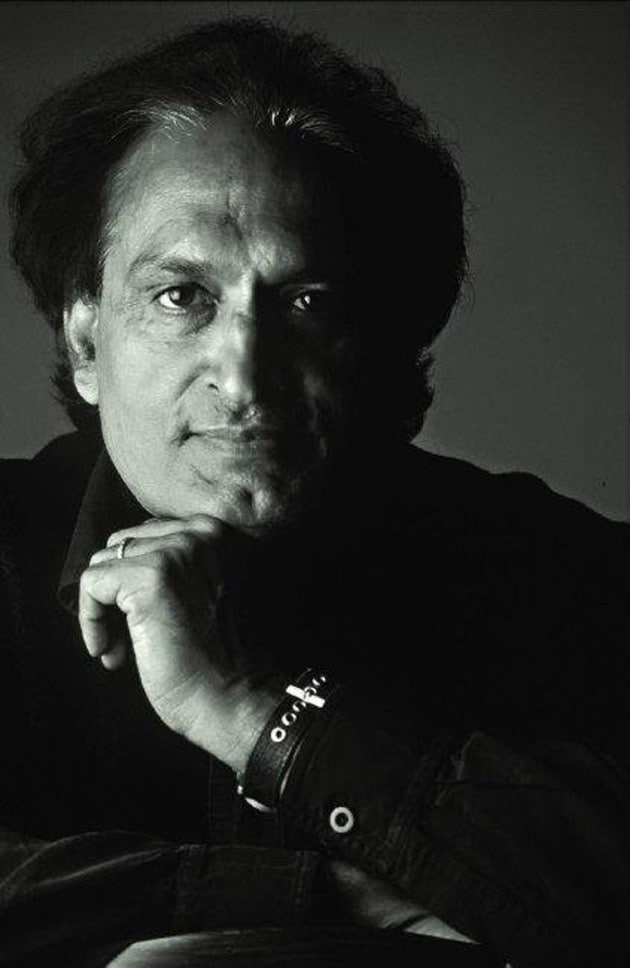

A look at the contemporary environmental and social situation in Bhopal through the lens of award-winning Magnum photographer Raghu Rai.

Updated: December 2, 2014 15:56 IST 1 / 22

1 / 22A look at the contemporary environmental and social situation in Bhopal through the lens of award-winning Magnum photographer Raghu Rai.

2 / 22

2 / 22Survivors of the 1984 Bhopal gas leak chain themselves in protest to the fence outside the Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister’s residence, demanding proper compensation, September 2014. Others stage a die-in, draped in sheets bearing the chilling image of a dead child - a photograph that has since become synonymous with the tragedy. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

3 / 22

3 / 22Rampyari Bai is one of Bhopal’s most persistent survivors. Now aged 90, she began her struggle in the wake of the disaster. In 1984 she was living with her son and his wife near the factory. Her daughter-in-law was seven months pregnant that night, and as the gas fumes filled the air, she suddenly went into labour. She and her baby died soon afterwards. Rampyari developed cancer and suffers from breathlessness, yet continues to fight for proper compensation. She says simply that protesting keeps her alive. “I will not leave this task of chasing governments,” she says. “Till my last breath, I will keep fighting.” (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

4 / 22

4 / 22Shahzadi Bi and her husband stand about 100 meters from her home, at the base of a pond which Union Carbide used to dump factory waste. Union Carbide lined the pond with plastic, the edge of which is visible in this picture. Shahzadi Bi was living with her family near the old Union Carbide factory the night of the deadly gas leak. “I was vomiting, had severe chest pain and eye irritation,” she says. Her husband fared no better - doctors told him that his heart was irreparably damaged by the leak. Their children suffer chronic chest pain. Her two other children, who were born after the 1984 disaster, have also been blighted by illness. “My daughter couldn’t conceive for four years after her marriage,” she says, adding: “Doctors had told her clearly that ‘since you have been drinking this toxic water, you will not be able to give birth.’" (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

5 / 22

5 / 22Shahzadi Bi, aged 60, lives in Blue Moon Colony, one of the 22 communities that surround the old Union Carbide pesticide factory. The area is ravaged by water contamination, caused by pollution caused by Union Carbide operations. “I am a victim of both disasters – the toxic gas leak and toxicity in drinking water,” she explains. The disaster overturned her and her family’s lives. “Everyone has dreams,” she says. “I too had those. My dream was not about becoming a teacher or doctor… I wished that we would provide a good education to our children… but the gas leak shattered all these dreams.” (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

6 / 22

6 / 22Shahzadi is now a member of a number of campaigning groups, including the Stationary Workers Association and the Bhopal Gas Victims Struggle Committee. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

7 / 22

7 / 22A woman who survived the 1984 toxic gas leak in Bhopal. She lost her relatives to the tragedy and now lives out her last days on a veranda, outside a shop. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

8 / 22

8 / 22Dr D K Satpathy, pathologist and former head of the Madhya Pradesh state Medico-Legal Institute, with foetuses of pregnant women who died immediately after the Bhopal gas leak. Dr Satpathy was working in the forensics department of Hamidia Hospital the night of the disaster. As patients died around him, he and his colleagues struggled to find a way to treat them. In desperation, the doctor on duty that night rang up a medical official at Union Carbide. The official's response, recalls Dr Satpathy, was that the accident was “not a serious matter”; his advice was to “put a wet cloth in their mouth and they will get well.” Up to 10,000 people died within three days of the disaster. Thirty years on, the total death toll is 22,000. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

9 / 22

9 / 22Dr D K Satpathy, pathologist and former head of the Madhya Pradesh state Medico-Legal Institute, recalls the horrific condition of the bodies he had to examine at Hamidia Hospital in the immediate aftermath of the gas leak. “I saw thousands of people lying there. Some were wailing, some were gasping, some were crying. I couldn’t understand what was happening," he says, describing the bodies he saw in the street just outside the hospital. "“No country must do hazardous business by compromising human health.” (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

10 / 22

10 / 22Safreen Khan (aged 20). Her mother Nafisha (aged 40) was taken away with the dead the night of the disaster, but was brought back home by her father Zabbar Khan when someone noticed she was still breathing. Safreen stands next to the statue erected in memory of the 1984 Bhopal gas leak in J P Nagar - right across the road from the abandoned Union Carbide plant. At 20, Safreen Khan is a new generation of activist. Too young to have experienced the disaster first hand, she has instead been defined by its aftermath. She first heard about the 1984 disaster and Union Carbide, the company responsible, when she was at school. “People have run out of patience," she says. "They still remember. They still cry and mourn for their family members who died that day. They feel that at least now, our government and the company must listen and take steps, because 30 years is too long… to get justice.” (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

11 / 22

11 / 22Sathyu (left) went to Bhopal as a volunteer a day after the gas leak and never left. Today, he is a founder member of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action and the Sambhavna Trust. In these 30 years, Sathyu has been a lynchpin for gas survivors, their children, and those affected by water contamination caused by Union Carbide factory operations. “The disaster occurred essentially because the government prioritized foreign investment over the life and health of ordinary people,” he says, adding: “The more awareness spreads on the continuing disaster in Bhopal, the more we will move towards achieving what we are still trying to achieve. Most of our hope is bestowed in public support.” Rachna Dhingra (R) left her job with a multinational management consultancy firm in the USA for Bhopal in 2003 after realising she could do something to help the communities there. She’s remained ever since and today is a member of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action. “Corporations cannot just come, kill and pollute, and leave without any kind of responsibility,” she says. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

12 / 22

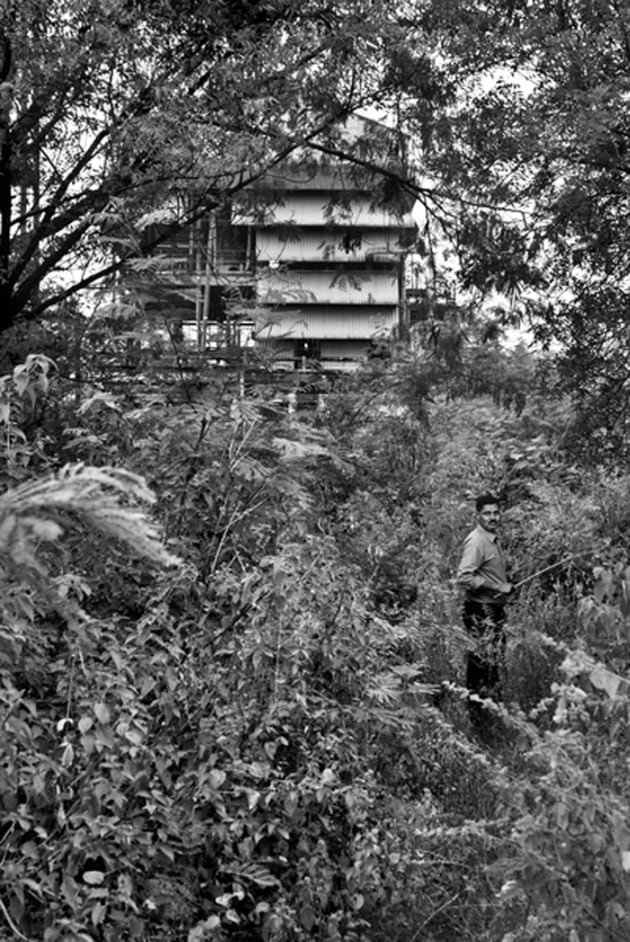

12 / 22Bhagwant Rao, a government security guard, stands in front of the abandoned Union Carbide factory. He was 15 years old at the time of the disaster and is one of thousands claiming compensation from the company. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

13 / 22

13 / 22A patient at Sambhavna Clinic, which runs free clinics for survivors of the gas leak. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

14 / 22

14 / 22The clinic, set up by activists, provides vital care where government efforts have failed. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

15 / 22

15 / 22Locals graze goats within the former Union Carbide compound. When Union Carbide abandoned the factory, it left behind pollution that has never been cleaned up. For decades, people living nearby were forced to drink water contaminated by these pollutants, leading to debilitating illness, including vision impairment, lung and kidney disease, and fertility problems. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

16 / 22

16 / 22Colony behind the abandoned Union Carbide factory. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

17 / 22

17 / 22Bhopal survivors protest in New Delhi, to extradite Warren Anderson, former chief executive of Union Carbide. Anderson is evading justice in the United States and is wanted by Interpol for crimes in 2001, Bhopal. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

18 / 22

18 / 22A view of the Bhopal town in 2002. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

19 / 22

19 / 221984: A man carries the body of his dead wife past the deserted Union Carbide factory, the source of the toxic gas that killed her the night before. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

20 / 22

20 / 22This victim was identified as Leela who lived in the Chola colony near the Union Carbide factory. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

21 / 22

21 / 22Mass cremation of victims held alongside the communal graves. (Source: Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos)

22 / 22

22 / 22