Opinion Year Of The Regional

Filmmakers are realising that language is not a limit.

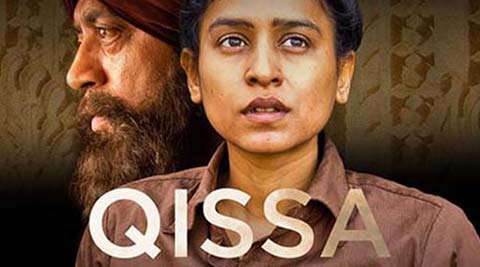

Many of the best films of 2015 spoke in tongues. Qissa was in Punjabi, Court was a mix, but mainly spoke in Marathi with bits of English, Hindi, Gujarati, Killa was again in Marathi, Kaaka Muttai was in Tamil, and Bahubali, the film that proved that Bollywood can dream up a canvas as big as any Hollywood tentpole, and execute it, too, was in Telugu.

Qissa is a moody, atmospheric exploration of themes our cinemas usually don’t go near to for fear of being deemed “too heavy” — the cages that patriarchy and gender build around us, and the Partition, both real and metaphoric, of a nation and its people. It is a film I think about often, both for what it says, and how it says it, as well as the first-rate clutch of actors in it: Irrfan, Rasika Dugal, Tillotama Shome.

Court feels less like a film than an explosive state-of-the-nation report, and how dismal things can be for those at the not-have end of the spectrum. It talks of power and powerlessness and how the haves keep up their sense of entitlement. Both Killa and Kaaka Muttai feature children, but not the annoyingly artificial kids that Bollywood serves up: These are real young people and their loss of innocence has both affection and weight. And Bahubali is really all about size: It is a mammoth movie, scaled to fill the frame and our eyes, filmed with verve and a passion for storytelling that transcends.

There were always great films being made in languages other than the kind of Hindi Bollywood propagates. The difference this year was that these “regional films” were not patronised and ignored, patted on the back with a national award or two, and then relegated to oblivion. These films invited us to stop and savour their distinctive plots and performances: I will look back at 2015 as the year that a real crossover of cinema began happening within the country. Unless this kind of cross-pollination takes place between states that are culturally and linguistically

different even if they share borders, there is never going to be a sizeable outward movement of Indian films conquering foreign shores, creating new markets.

We saw these films in subtitles and dubs, and though there is always something that is lost in translation, and dubbed movies are usually irritating because of the mismatch in synch (voice to lip movements), it did not matter, because access has always been an issue. The new generation of Indian filmmakers is beginning to realise that their films do not have to be circumscribed or limited by language. Good cinema will travel and find its feet wherever there is hunger for it. That was really the highpoint of this year, which saw a bunch of terrific debutant directors with distinctive voices. Court, Killa and Kaaka Muttai are all first features. So are Masaan and Titli, both in Hindi, both very different in tone and texture, but both powerful explorations of the clash between generations and expectations, and how conflict between class and caste can make way for some kind of resolution. You wish these talented first-timers well, and hope that they can stay away from hubris and go on to the really tough thing: Repeat the act. Because if we need Bollywood to switch from its turgid, exhausted formulas, we need fresh voices to grow louder and more impactful.

On that note, it is time to call out the powerful Khans and Kumars of the industry. Akshay may have done let’s-catch-the-terrorists caper Baby and Salman may have buoyed Bajrangi Bhaijaan, a cross-border entertainer, but net net, none of the Big Boys of Bollywood stuck their neck out, especially not Shah Rukh, who did the same old for the nth time in Dilwale. It may have made money and have a star still able to coast on charisma but it has no freshness or sparkle. It is a film created to fatten bottom lines, and not anything else.

Hollywood, which has always been a presence but not enough to worry the Bolly pashas, is now getting bigger. Audiences are now impatient with also-rans and bad copies. Solid plots, please, and drama, not melodrama. Time to throw out the old. And embrace the new.