Opinion Reverse Swing: Lanka lessons for Modi

What the Prime Minister can learn from the recent elections in the Emerald Isle.

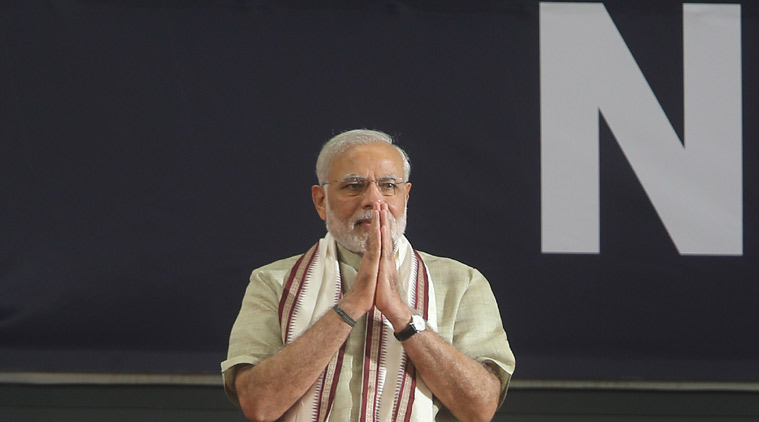

India, as always, is watching Colombo closely, and Narendra Modi should draw two lessons from Rajapaksa’s defeat. The first is broadly national, the second personal.

India, as always, is watching Colombo closely, and Narendra Modi should draw two lessons from Rajapaksa’s defeat. The first is broadly national, the second personal.

India has reason to be riveted to Sri Lanka, and not merely because of the beguiling Test series currently underway.

The beautiful island with a cruel modern history has just voted in its parliamentary elections — and voted with impressive sophistication. Citizens have handed a second consecutive spanking to Mahinda Rajapaksa, the uncouth and undemocratic strongman who was for so long the country’s president.

Having tasted a stunning defeat in the presidential elections earlier this year, Rajapaksa was attempting to return to power as prime minister. This would have allowed him to act as a “roadblock” on the island’s path to democratic recovery — a recovery that would include, presumably, some judicial scrutiny of Rajapaksa’s own role in the massacre of Tamil civilians in the civil war. Mercifully — for Sri Lanka as a whole, and its Tamils in particular — he lost. May this be the end of the road for a disgraceful man.

India, as always, is watching Colombo closely, and Narendra Modi should draw two lessons from Rajapaksa’s defeat. The first is broadly national, the second personal.

The routing of Rajapaksa and the consolidation of political forces that have come to power by rejecting his methods and ideology offer India a massive opportunity to rebuild relations with Sri Lanka. A neighbouring country that should, by nature, have as much affinity with India as does Nepal, had been sold to the Chinese by Rajapaksa, who saw in Beijing not merely a venal opportunity for enrichment, but a delicious way to stick it to India.

Modi (and India) can take great heart from the fact that both President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe are eager to restore India to the position of prime ally. The Chinese presence in Sri Lanka is disconcerting to many of the country’s citizens, who, even as they understand the economic potential of a partnership with Beijing, are loath to secure this advantage at the expense of their instinctive fraternity with India.

Yet even as Sri Lankans are India’s natural allies, they are — like the Bangladeshis and Nepalis — sensitive to being dominated or patronised by their massive neighbour. So Modi must approach the new government in a spirit of magnanimous partnership, ever alert to the dangers that could arise from an assertion — however subtle — of India’s regional pre-eminence. Open-hearted relations with Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal must remain the cornerstone of India’s neighbourhood policy, and that must include the making of as many economic and political concessions to these countries as possible.

If only India spent on Sri Lanka (and our other, civilised neighbours) a fraction of the attention it pays to its relations with Pakistan! As far as the latter is concerned, India needs to get real and understand that its focus must be adamantly defensive: which means doing everything in its power to ensure that Pakistan can do as little harm to India as possible. Anything else is a waste of time.

The second tutorial offered to Modi in the debacle of Rajapaksa is in what happens to an elected politician who comes to believe that he’s the embodiment of his own country, and that he alone knows what’s best for his country and its people. To see too much symmetry between Modi and Rajapaksa would be wrong, of course, and I’m not suggesting they’re political twins; but there are enough similarities for us to be able to say to Modi, “Look at Rajapaksa, and at what happened to him.”

Modi doesn’t quite have Rajapaksa’s level of megalomania, and he certainly didn’t wage war on innocent civilians. (And no, whatever you may think of Gujarat in 2002, it bears no comparison to what was done to Jaffna.) And unlike Rajapaksa, Modi has no family “ecosystem” that thrives on its proximity to power and money.

But Modi has a dirigiste temperament that cuts him off from public opinion, and from contact with civil society and the press. Like Rajapaksa, he sorely lacks humility, and brooks no opposition. Unlike Rajapaksa, however, Modi has the capacity to learn from his own mistakes. And unlike Rajapaksa, his hubris isn’t unlimited.

Or so one hopes—for Modi and for India.

Tunku Varadarajan is the Virginia Hobbs Carpenter Research Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution

Follow Tunku Varadarajan @tunkuv