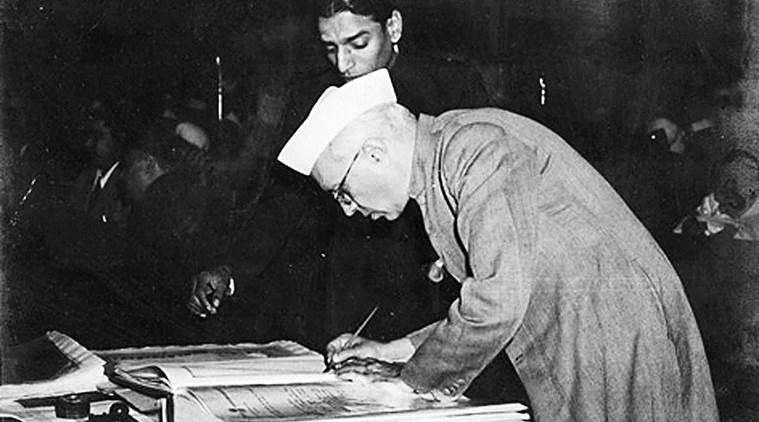

Opinion As They Write Nehru Out

It’s instructive to recall his legacy at a time when efforts are on to relegate him.

In today’s India, when the protests of the creative class are berated as politically motivated, a small incident from Pandit Nehru’s life serves as a reminder of the freedom of expression, a precious commodity now.

In today’s India, when the protests of the creative class are berated as politically motivated, a small incident from Pandit Nehru’s life serves as a reminder of the freedom of expression, a precious commodity now.

It appears appropriate to look at great men of history through the lens of their big projects, but their true character can be known only through their small gestures. In today’s India, when the protests of the creative class are berated as politically motivated, a small incident from Pandit Nehru’s life serves as a reminder of the freedom of expression, a precious commodity now. In 1962, a cartoon of Nehru by R.K. Laxman was published. Far from taking offence, Nehru rang up Laxman and said, “I so enjoyed your cartoon this morning. Can I have a signed enlarged copy to frame?”

Around 1947, several countries broke free of the colonial yoke. Yet, few are vibrant democracies like India. The freedoms we defend today, the universal suffrage we enjoy, are indebted to Nehru’s inclusive vision. Thanks to his efforts, India, a poor country riven by caste, language and dozens of fractious states, enacted universal voting rights much before many developed countries. Switzerland, for instance, introduced universal adult suffrage only in 1971.

The challenges that awaited newly independent India are hard to envision today. Partition had come at a steep human cost. Not a family in north India was untouched by the rupture. If Gandhiji led the moral force of tolerance and nonviolence, it was Nehru who wove these principles into state policy. Between him and his home minister, Sardar Patel, the princely states were brought under the sovereign umbrella, even as doomsayers predicted the failure of this historic project.

But the assimilation of the princely states was just the beginning. India also had to be fed. Famines occurred regularly in enslaved India, and millions died in the Bengal famine of 1943. Fortunately, Nehru was an institution builder. He not only remedied British famine policies but also funded and catalysed research that went into the Green Revolution. The PDS was implemented to provide subsidised foodgrain, and between 1947-64, organisations such as the Central Rice Institute in Cuttack, the Central Potato Research Institute in Shimla, and universities such as the G.B. Pant University were established. Nehru’s efforts led to the introduction and adoption of high-yield wheat hybrids on a large scale. These policies rescued generations of Indians from malnutrition and poverty.

As India races past Mars into the far reaches of the solar system, one must step back and look at the inspired beginning of India’s space programme. In the 1960s, only the mightiest nations were thought to be capable of going into space. Nehru foresaw that success in space would be critical for India’s stature. Scientists like Vikram Sarabhai and M.G.K. Menon were instrumental in turning Nehru’s vision into a reality. It is a tribute to Nehru that India’s space programme was not born out of military needs but of a dream of being able to launch satellites. As we celebrate Nehru’s birthday and battle efforts to belittle his legacy, we need to relearn his contribution to the making of modern India.

The area in which his contributions are most discussed are foreign policy. In the late 1940s, as countries were gaining independence and trying to find their ideological moorings, Nehru, along with Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Sukarno of Indonesia and Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia devised the non-aligned doctrine. This moderated international politics and tempered the extremes that pushed the world to the brink of war more than once during the Cold War years. In fact, Nehru’s international engagement started even before India gained independence. The Congress criticised Nazism and Fascism even when more established nations in Europe seemed oblivious to the peril at their gates. This engagement continued after Nehru became prime minister.

Early in 1947, at the initiative of India, the Asian Relations Conference was convened in Delhi, where the foreign policy principles of independent India were proclaimed. Nehru also participated in the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung in 1955, and popularised non-alignment there. These conferences emphasised economic and cultural cooperation, respect for human rights and self- determination, and the promotion of world peace. Decades later, these remain the cornerstones of India’s soft power, our Look East policy and prominent role in international peacekeeping.

As parochialism of the narrowest variety seeks to rewrite history to besmirch Nehru’s contributions, it is instructive to be reminded of his legacy. We must ensure that the efforts to write India’s tallest statesman out of the institutions that celebrate him and his contributions do not succeed.

The writer, a former Union minister, is a member of the Congress party