Somewhere in North Kolkata

A flyover crash brings Burrabazar into focus — once a hub of affluent Marwaris, it is now a place for those who have nowhere to go.

Gayatri devi Nagnolia (66) and Shiv Kumar Nagnolia (72) check out the crash site from their window. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Gayatri devi Nagnolia (66) and Shiv Kumar Nagnolia (72) check out the crash site from their window. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

The marble-laden yellowing floor of 4, Kali Krishna Tagore Street has evidently seen better times. Gayatri Devi Nakhotia, 66, covers her head with her pallu as she leads us through second-floor apartment. “We have lived here for generations. There was a time when Belgian chandeliers would hang from the ceilings,” she says. The first time she walked into this house, 50 years ago, Gayatri Devi was a girl from the mining town of Jharia with dreams of seeing a big city. “I belonged to a conservative Marwari family. Getting married into a Marwari family from Burrabazar in Kolkata was a dream come true,” says Gayatri Devi. Having lived that “dream” for half a century now, life has made her more cynical.

For the past three weeks, Gayatri Devi, her husband Shiv Kumar Nakhotia and 20 other families who live in this 80-year-old building, have been living the life of refugees. They have been asked to vacate their homes for a month in the aftermath of the Vivekananda flyover crash last month. But the family has no place to go. “All our relatives have deserted us for a better life in other parts of the city. No one will care about us, we don’t matter. Only those Marwaris who have nowhere to go stay in houses like this in Burrabazar,” says Gayatri Devi.

The sizeable Marwari community of Kolkata, can be divided into two groups: those who have made it out of Burrabazar, those who haven’t. Author Alka Saraogi, who has written about the Marwari community of Kolkata in her Hindi novels, says, “Even a century ago, most Marwaris of the city lived in the Burrabazar area. This is where they built their houses, this is where they traded from, this is where they built their Laxmi-Narayan temples.” Till WWI, the Marwari community of the city would earn all their money in the city and build havelis in Rajasthan. “Since we come from a desert state, we always had the foresight to save, to make provisions for the future. We built beautiful havelis with jharokhas in Rajasthan, but lived austerely here,” says Saraogi. By the 1940s, Burrabazar was the trading hub of Kolkata and also home to a Marwari population of almost a lakh.

It was during the Bengal famine of 1943 that Burrabazar first came into disrepute. Some members of the thriving trading community were accused of hoarding grains and later selling them at steep rates on the black market, a taint that refused to vanish despite all the philanthropic work the community has done for the city. “My grandparents, who also lived in Burrabazar, shifted to south Kolkata,” says Saraogi.

Being a Marwari from Burrabazar did not open all doors in the city. Rajesh Gupta, 30, who lived less than a kilometre away from the flyover, never told his classmates from St Xavier’s College that he lived in Burrabazar. “I would tell them I lived in north Kolkata. I didn’t want to be seen as an orthodox baniya. Now that I think about it, I feel embarrassed, but then I was a young boy who wanted to be accepted in a college where being cool mattered,” says Sharma, who is a PR professional in Singapore now.

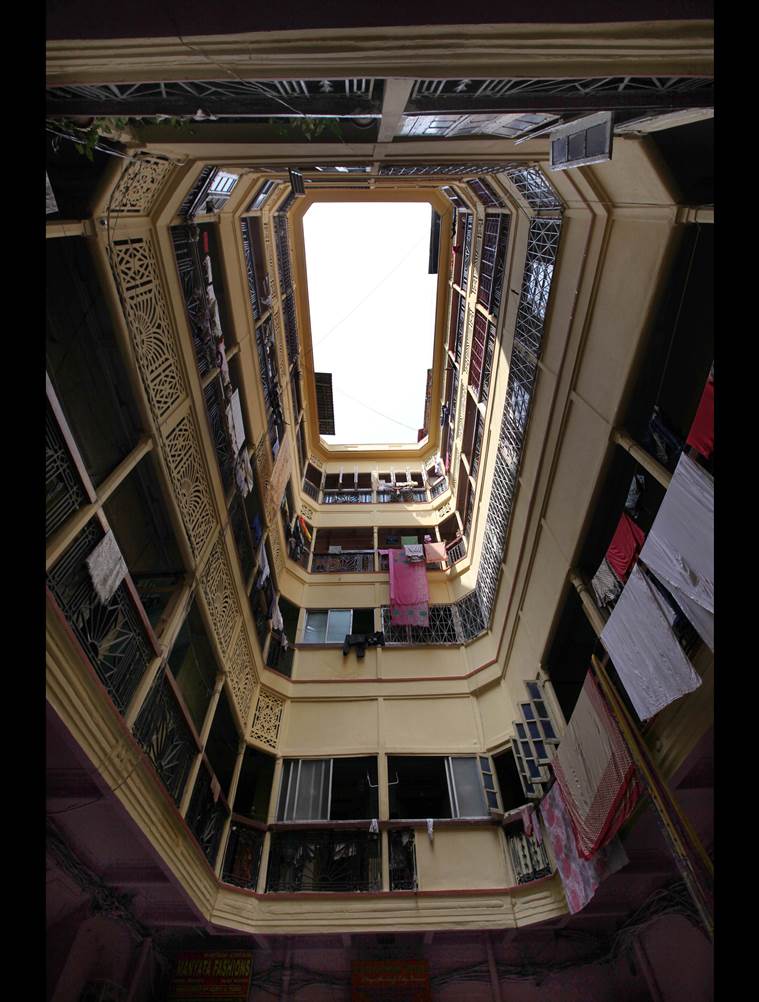

One of the affected house on Kali Krishna Tagore street. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

One of the affected house on Kali Krishna Tagore street. (Express photo by Partha Paul)

Marwaris have had quite an illustrious role to play in Bengal’s history. In his blog hajarduari.wordpress.com, Garga Chatterjee, a research affiliate with Massachuesetts Institute of Technology, US, observes that the Marwaris were a conspicuous part of the entrepreneurial and industrial initiatives that was responsible in making Kolkata the “greatest city between Aden and Singapore” once upon a time. “The philanthropic initiatives in Kolkata by the Marwari business houses are second to none. The dismal condition of the state’s apex health facility, the SSKM hospital, does not do justice to its large Marwari benefactor Seth Sukhlal Karnani, who was also instrumental in bringing a precocious virtuoso from Kasur (near Lahore) to Kolkata, giving the world Lata Mangeshkar’s early idol, Noor Jehan. Walk over to the Sambhunath Pandit Street and you will be standing in front of the only specialised neurology institute in West Bengal, the Bangur Institute of Neurology. The Marwari House of Bangurs were also the donors who set up the Bangur Hospital near Tollygunge,” says Chatterjee.

The hospital, where most of the victims of the Vivekananda flyover crash were taken, was also built by a consortium of Marwari benefactors in the early 20th century. In popular Bengali culture, Marwaris have always been projected as scheming businessmen intent on making money. Even filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, claims Saraogi, was guilty of stereotyping the typical Marwari. “In Ray’s celebrated classic, Joy Baba Felunath, Maganlal Meghraj, played by Utpal Dutta, was a Marwari businessman who was corrupt. Dutta, played the part to perfection, bringing that Marwari twang to his Bengali. The way he dressed, his body language was also very authentic. Which is why, it has become even more a potent reaffirmation,” says Saraogi.

Over the last century, a large chunk of the Marwari populace did escape to the leafy avenues of Ballygunje, New Alipore and Salt Lake. They also gained entry into the posh clubs of Kolkata. But there was also an eagerness to wish away their Burrabazar past, feels Saraogi. The second chapter of her celebrated Hindi novel, Kalikatha Via Bypass, is called “Somewhere in North Kolkata” for that very reason. “Most Marwaris who have moved on in their life, settled in more affluent parts of the city, want to dissociate themselves from their Marwari past,” says Saraogi.

Even in the pre-Independence era, Marwaris of Burrabazar had the reputation of being orthodox. “This was the era when Bengali women from all spheres started taking part in the freedom struggle. On the other hand, the Marwari women, who started arriving in Calcutta during the 1910s-1930s, led a very cloistered life. “They would need to cover their head when they left home. They couldn’t venture out of their home unchaperoned,” says Saraogi.

Less than a kilometre away from Gayatri Devi’s apartment is Tagore Castle. There is nothing castle-like about the old, greying buildings with honey-comb like apartments. In one of these apartments stays another Marwari family, another victim of the flyover crash, the Kandois. Abhishek, 24, and Nikhil Kandoi, 23, lost their parents Ajay Kumar and Sarita Kandoi in the flyover crash. “My father, was a timber merchant with an office near the crash site. He was the only earning member of the family. All his life, he dreamt of moving out of this hell-hole. That dream will remain a dream,” sums up Abhisek Kandoi.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05