The game is afoot: Assollant’s Captain Corcoran finally reaches Indian bookstores

Alfred Assollant’s creation, Captain Corcoran, finally reaches Indian bookstores, 159 years after the character landed on our shores.

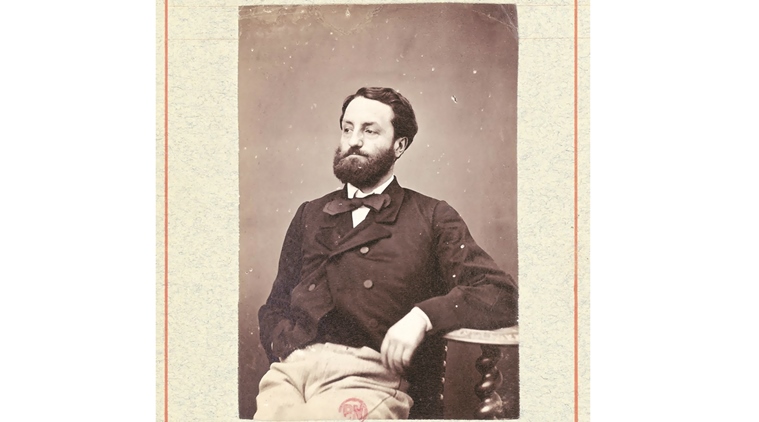

Oriental Express: Alfred Assollant was Jean-Paul Sartre’s favourite pulp writer.

Oriental Express: Alfred Assollant was Jean-Paul Sartre’s favourite pulp writer.

In June, this column had raised the spirit of Talbot Mundy (1879-1940), writer of rattling good yarns set in British India, now almost completely forgotten in both England and in India. This week, Sam Miller brings us an even more comprehensively forgotten yarnsmith — the French popular writer Alfred Assollant (1827-1886), whose creation, Captain Corcoran, travelled to India with a pet tigress named Louison in attendance, to find himself in the thick of the storm of 1857. Once Jean-Paul Sartre’s favourite pulp writer, he is forgotten in his native France, is completely unknown in India and, apparently, has not been translated into English until now. Miller’s translation, published by Juggernaut, retains the original title, The Marvellous Adventures of Captain Corcoran. But it tacks on an improbably contemporary subtitle, Once Upon a Time in India, which is up there in lights.

Miller ascribes Captain Corcoran’s failure to cross the Channel to Assollant’s evident dislike for the English. The writer visited England and met them in person. Perhaps, they didn’t let him walk on the grass. Perhaps, they gave him warm beer. By whatever means, they managed to alienate both author and character forever. The book teems with sentences designed to displease English sentiments, such as: “He placed the muzzle of his revolver against the skull of the Englishman, and blew his brains out.” It presages the staple image from the Commando comics, in which a Messerschmitt pilot has a Spitfire in his crosshairs and whispers, “Die, Englander pig-dog!” Ironically, Corcoran’s view of Indians is as Orientalist as that of English adventures set in India.

At home, Assollant’s descent into obscurity owed to principled tactical imprudence — he chose the wrong side. Fiercely Republican, he wrote against the regime of Napoleon III, which made it impossible for him to work for the government. He tried to make a living from books, and churned out one every year for ever, but only Captain Corcoran was a success. He died in penury and obscurity, though he was buried in Pere Lachaise, perhaps the world’s most visited cemetery, where he shares hallowed turf with Moliere, Chopin, Rossini, Balzac, Proust, Oscar Wilde, Bellini and, most famously, Jim Morrison.

Assollant never visited India, like his much-admired cultural heir HRF Keating, who churned out nine novels featuring Inspector Ganesh Ghote of the Bombay Police without even setting eyes on the Gateway. That spectacular run, starting with The Perfect Murder (1964, made into a Mechant-Ivory film), ended when he did come to India. Thereafter, apparently, he found it harder to write Inspector Ghote books — a fine instance of travel constricting the mind.

Keating got away with it because by his time, there was ample material for armchair travellers, and writers who wanted to conjure up locations they had never set eyes on. Assollant didn’t enjoy that good fortune, and may have relied on contemporary European yarns and classical authors like Pliny. And so he has anomalies like an encounter with a rhinoceros in central India. He places his hero in the company of a Prince Holkar, which would have been a reasonable choice for a slightly earlier time, when the Maratha confederacy had deployed troops across the subcontinent and threatened Calcutta. They were natural partners of the French, who were trying to emerge as a countervailing force in Asia. One of modern Kolkata’s busiest roads was once known as the Maratha Ditch, a fortification intended to break the momentum of enemy cavalry and impede the movement of gun carriages. But Miller writes that by the time of the Rising, the Holkars supported the British. And therefore, they should have earned Assollant’s displeasure.

Apart from the British, Assollant was presciently suspicious of the Germans. But he was quite even-handed in his dealings with all nationalities, even his own. The book opens with a withering account of a boring afternoon in the Academy of Sciences in Lyon, where a savant had put the entire faculty to sleep by reading from “the shorter version of his Collected Works, telling them about his research on the subject of the footprints left in the dust by the left legs of a hungry spider.”

Into this haven of arcane somnolence, one day in 1857, steps a 25-year-old Captain Corcoran, bearing a revolver and a dirk, and amazes the savants by speaking effortlessly in English, Hindustani and Sanskrit, and calling for a copy of the Bhagavad Gita in case anyone needs an exegetical rendering. And at his call appears a royal Bengal tigress, aged five, who will travel with him in search of an Indian guru.

This is only the first volume of the adventures of Captain Corcoran, published by Louis Hachette in 1885. Another volume remains out of bounds to the English reader, and one hopes that Sam Miller will treat this as a matter of urgency.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05