Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

The Big Picture: After the waves pulled back

Arun Janardhanan travels to Dhanushkodi and Nagapattinam and finds stories of hope amid the ruins.

The Nagapattinam coast now. It had been wrecked by the 2004 tsunami.

The Nagapattinam coast now. It had been wrecked by the 2004 tsunami.

Two natural disasters struck the coast of Tamil Nadu, both in the month of December — one, a cyclone 50 years ago, and the other, the tsunami of 2004. Photographs by Oinam Anand

NAGAPATTINAM

10 years later, lives by the sea

Parameswaran and Choodamani with sons Shamiah and Michaiah. Both children were born after the tsunami.

Parameswaran and Choodamani with sons Shamiah and Michaiah. Both children were born after the tsunami.

Kirupasan, 5, paused midway through a backhand throw of his frisbee and stared at the sea. His father K Parameswaran hunched forward in anticipation of Kirupasan’s throw, his back to the sea. Just then, the boy let out a guttural shriek and Parameswaran looked over his shoulder to see a monstrous wall of water behind him. He yelled out to his son to run up the shore.

“I grabbed Kirupasan by his fist and kept asking him to run faster. He tried his best but the wave caught up with us and whipped us upwards. I remember holding on to my son’s hand even then. But at one point, the waves crashed and that’s when my grip loosened,” says Parameswaran, 50, an executive engineer with Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited who also runs an orphanage in Nagapattinam.

Ten years after the tsunami that crashed into their Sunday morning picnic at New Beach in the coastal district of Nagapattinam, Parameswaran says he remembers the day like it was yesterday. “I remember my daughters Karunya and Rashanya playing near the water, making patterns in the wet sand. That’s an image that will stay with me. The wave that hit me flung me some 750 metres away from the coast and thrashed me against a palm tree which I managed to cling on to. From there, I saw people drowning. Everything was over in an instant,” he says from his house in Nagapattinam. It’s a two-storeyed house by the beach, with the three-storeyed orphanage building abutting it. From his gate, the sea looks calm and benign, just the way it was that Sunday morning 10 years ago, minutes before the tsunami struck.

Ten years after the tsunami that crashed into their Sunday morning picnic at New Beach in the coastal district of Nagapattinam, Parameswaran says he remembers the day like it was yesterday. “I remember my daughters Karunya and Rashanya playing near the water, making patterns in the wet sand. That’s an image that will stay with me. The wave that hit me flung me some 750 metres away from the coast and thrashed me against a palm tree which I managed to cling on to. From there, I saw people drowning. Everything was over in an instant,” he says from his house in Nagapattinam. It’s a two-storeyed house by the beach, with the three-storeyed orphanage building abutting it. From his gate, the sea looks calm and benign, just the way it was that Sunday morning 10 years ago, minutes before the tsunami struck.

“There was no warning. There were people who had come to the beach to watch the sun rise, youngsters playing volleyball, others playing cricket,” he says. Parameswaran had brought his children and seven of their relatives, who were visiting them from Karnataka, to the beach. His wife Choodamani, who works with Life Insurance Corporation, had stayed behind at home to organise breakfast and lunch for their guests.

“The water receded in a few minutes. Almost an hour later, I found the body of my daughter Rashanya floating near my house, barely 800 metres away. She was 12 years old. I took her body up to the terrace and went looking for my other two children,” he says. Next, he found Kirupasan’s body in his neighbour’s compound — “he lay still, like he was sleeping” — and laid him next to Rashanya. That’s when someone alerted Parameswaran of a girl’s body in the bushes outside his house. “I saw a group of people dragging the body of a little girl, trying to disentangle it from the thorny bushes. It was my Karunya. She was 9 then. I shouted at those people, sat there and carefully removed the thorns that had made sharp cuts across her face,” says Parameswaran.

When they had to bury their children later that evening, Choodamani insisted they be laid to rest in the same grave, with each other for company. “I sent a friend to Nagapattinam town to get some flowers before the burial. But the shops were shut and the entire city was evacuated. So I couldn’t even do that for my children,” he says.

The next couple of days, Parameswaran and Choodamani searched for the bodies of their relatives and recovered those of five of the seven. On the third day, they put these bodies in trucks along with several others, for a mass burial in Nagapattinam.

It’s only then that the extent of the tragedy sunk in. “We decided we would consume poison and end our misery. But before doing that, Choodamani wanted me to take her to the town to see the extent of the damage,” he says.

While in the town, they saw people pushing and jostling as a relief truck distributed food packets. They joined the crowd and got four food packets. They hadn’t eaten anything in four days, but, Parameswaran says, they took the food to a fisherman colony. “There, we found many children who had lost their parents and many parents who had suffered losses far bigger than ours. That was when Choodamani said we should open a home for these children,” he says. Since they had four food packets, they took four children home with them. Gradually, they took in more children, till they had 30 of them, all orphaned by the tsunami.

As that first batch of children grew up and left home, the couple brought in more children, most of them orphans from Nagapattinam. “Our children have done well for themselves – we have a marine engineer, an MBA and so on. We have always had 30 children… in fact, 32,” says Choodamani, turning to eight-year-old Shamiah and six-year-old Michaiah, the two boys she gave birth to in the years after the tsunami.

Life in reverse

A year after Kumari got her tubectomy reversed, Kamalesh was born.

A year after Kumari got her tubectomy reversed, Kamalesh was born.

Kumari S, 38, was among several women in Nagapattinam who, after losing their children in the tsunami, underwent reverse tubectomy.

“After we lost two of our three daughters, my husband wanted us to have a baby again. I delivered Kamalesh the next year at a temporary shelter in Nagapattinam town,” she says, helping the 9-year-old slip into his white school uniform.

Since many of those who died in the tsunami were children, the Jayalalithaa government issued an unprecedented order formalising the sterilisation reversal procedure. At least 1,766 children had died in Keechankuppam, Nagoor, Nambiyanagar, Vellankanni, Siruthur and Akkaraipettai villages of Nagapattinam. Akkaraipettai, a village surrounded by water on three sides, is where the tsunami hit the hardest, killing 1,800 people.

That morning in Akkaraipettai, Kumari was cleaning the window and door panes of her house. Two of her daughters were playing outside while her husband M Sivakumar, a fisherman, and her eldest daughter were inside the house. “Our verandah faces the sea and I heard a loud thunder. Before I knew it, a huge wave had crashed into the house. I managed to cling on to a shelf. As the water rushed in and rose rapidly, I barely managed to keep my head above water. I saw my husband hanging onto the ceiling fan and pushing our eldest daughter onto the top of the shelf. We stayed that way for about 15 minutes until the water receded,” she says.

But the worst was to follow. Kumari says that while they found the body of their youngest daughter, four-year-old Sandhya, the same day, they could never find nine-year-old Nithya’s body.

After a month in hospital, Kumari and her family were shifted to a temporary shelter where they lived for the next two years until they were allotted a house at Tata Nagar, a tsunami rehabilitation colony that now houses more than 800 families.

A senior doctor at Kilpauk Medical College in Chennai recalled that within a year of the tsunami, at least 80 cases of reverse sterilisation were done in Tamil Nadu. “The government’s order on reverse sterilisation helped many couples bear children after the tragedy. Several such cases were referred to Kilpauk Medical College, while many private hospitals charged up to Rs 2 lakh for the procedure.”

There was a flip side though. “These were people who had lost everything, but were willing to pay anything to be parents again. And when that didn’t happen, some of them developed serious mental problems,” he says.

No goodbyes in a burial dump

That day, Annadurai ran to hospital with his son’s bloated, listless body slung over his shoulders. The waves had killed 13-year-old Dinesh while he was playing near the beach. “I ran all the way to the hospital. His body had started decomposing and was smelling, but I kept hoping he would be alive,” says Annadurai.

But he had no time to mourn. In the days following the tsunami, gravediggers were in great demand. So was Annadurai. The authorities had converted several spots in Nagapattinam into mass graves. Trucks arrived at doorsteps to collect the dead and dumped them at burial sites. One such truck carried Dinesh’s body.

“We dug at least seven huge pits here and about 100 bodies went into each of them,” says Annadurai, who works at the same open graveyard in Nagapattinam town even now. “The trucks would come, dump the corpses into the pits and a crane would cover them with mud. My son’s body went in like that,” he says.

A house of lights

The church is the main draw at Dhanushkodi.

The church is the main draw at Dhanushkodi.

By the end of the day, the lighthouse was the last man standing, the town it towered over in ruins. S Ravichandran, now an assistant executive engineer with the Directorate of Lighthouses and Lightships in Delhi, was the engineer in charge of the Nagapattinam lighthouse that day. It was a Sunday and Ravichandran was on duty. Ravichandran and his family — wife and two children — lived in the official quarters in the same compound. “Around 8.15 am, a Tamil news channel reported the earthquake. I didn’t think much of it. I went to the market and returned by 8.50 am. Within minutes, the sea began to look different. Soon, huge waves hit the coast,” he says.

As the water gushed into the compound that houses the lighthouse, Ravichandran shouted out to his wife who was in the kitchen and ran up to the office room where his two boys were playing games on the computer. “By the time I entered the office, the water had started rising. I hoisted my children onto my shoulders and remained standing. Within seconds, the room had turned into a water vault and I dangled from a beam on the ceiling with my boys on my shoulders. We stayed that way for 15 minutes till the water receded,” he says.

Luckily, he recalls, his wife managed to come out of the kitchen and climbed onto the roof of the toilet. An hour later, the family left the compound to move to a friend’s house far away from the beach. “I had to return in the evening to operate the station. I saw five bodies strewn inside the compound, all of fishermen,” he says. Though the lighthouse itself wasn’t damaged, equipment worth Rs 3 crore had to be replaced.

But that evening at the lighthouse, Ravichandran says, the lights came on again.

DHANUSHKODI

50 years ago, the train that vanished

Trains from mainland cross Pamban bridge to get to Rameswaram, the last stop now.

Trains from mainland cross Pamban bridge to get to Rameswaram, the last stop now.

December 22, 1964. 11 pm. Train No. 653 had set off an hour earlier from Pamban station with 110 passengers and five railway staff, its last run for the day. It was now yards away from Dhanushkodi station. The rain that had started a week ago had got stronger and it lashed heavily against the train’s window panes. In the dark, the sea gave nothing away. Just then, a giant wave rolled up and… the train was gone. So were 115 people on board. All dead, according to a stone plaque about 5 km ahead of Dhanushkodi.

The plaque goes on to say: “Over 200 people who lived on the Dhanushkodi coast also died in the cyclone. All the houses in Dhanuskodi were blown to pieces in the storm and marooned.”

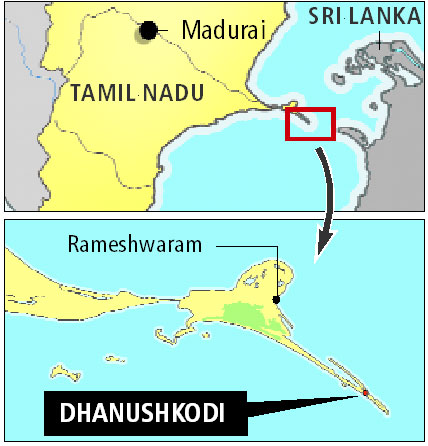

Pamban island, on the eastern coast of Tamil Nadu, narrows rapidly till it appears as little more than a line smudge in the inky blue of the ocean. Dhanushkodi lies here, at the tip of this strip of land. It is a town caught in a freeze-frame. For 50 years now, its roofless buildings have held up the sky, the twisted metal of the rail tracks drawing a trickle of intrepid tourists and amateur photographers.

Pamban island, on the eastern coast of Tamil Nadu, narrows rapidly till it appears as little more than a line smudge in the inky blue of the ocean. Dhanushkodi lies here, at the tip of this strip of land. It is a town caught in a freeze-frame. For 50 years now, its roofless buildings have held up the sky, the twisted metal of the rail tracks drawing a trickle of intrepid tourists and amateur photographers.

The road from Pamban ends at Mukundarayar Chathiram, after which it’s a 30-minute rough drive, the sea closing in on either side. The town now has a population of about a 100 people, mostly fishermen. The church without the roof is the biggest draw, with tourists scaling its limestone walls to pose for photographs. There are more ruins — of a Shiva temple, and of the railway station-cum-port office with a full-fledged post office. Also, of a school, its toilet blocks and window-panes still intact.

Twisted rail tracks, the only remnants of the train that vanished in the 1964 cyclone.

Twisted rail tracks, the only remnants of the train that vanished in the 1964 cyclone.

But this wasn’t the town K Mahalingam remembers from his childhood. “Dhanushkodi was a bustling town, at least by the standards of those times,” he says. It had a school, a full-fledged hospital with doctors and nurses, a port and a post office. There were two temples and a church for its over 1,000 inhabitants. The town was connected to the mainland by road and rail. “The temple town of Rameswaram wasn’t so big then and Dhanushkodi was a bigger centre. There were at least 200 families in Dhanushkodi, mostly Brahmins, who were railway employees or worked for India Post and the port offices. The death toll in the cyclone would have been far higher if it wasn’t vacation time and most of these government employees and their families weren’t away. Dhanushkodi and Pamban island were fully cut off from the mainland,” recalls Mahalingam, one of the few survivors of the cyclone who now lives at Rameswaram town.

Mahalingam was 14 years old in 1964. He recalls how that morning, elders in the town had looked up at a flock of birds flying over the coast and warned of imminent danger. They had called it right. The cyclone hit the coast between 11.30 pm and midnight and his house near the harbour was washed away.

Mahalingam’s brother K Kumar wasn’t born then, but has grown up with stories of Dhanushkodi that his father Neechal Kaali told him.

Kaali, a fisherman who died at 90 in 2010, was among the few survivors of the cyclone. His interviews in mainstream dailies provide probably the only account of the missing train and the Dhanushkodi of 50 years ago. Kaali, who got the name Neechal (swimming in Tamil) after he swam from Dhanushkodi to Sri Lanka, told the story of the cyclone to anyone who cared to listen — the townsfolk, reporters and tourists. With every retelling, the story of the train, rain, sea, cyclone and how he survived that night by “clinging on to a pole” grew in magnitude, almost matching the scale of the “20-foot-high waves” that struck the town.

That night, after the train vanished without a trace, it took more than 48 hours for the news to reach railway authorities on the mainland. The Pamban rail bridge, connecting the island with the mainland, was also washed away. The 300-odd residents who survived the cyclone had to wait for over a week before they were shifted to Mandapam on the mainland, 40 km away from Dhanushkodi.

During an aerial survey of the coast a week later, then Tamil Nadu chief minister M Bhaktavatsalam is said to have spotted the train’s engine, probably the only ‘evidence’ of a train that once was. The government had then subsequently declared the Dhanushkodi coast as unfit for human habitation.

Kumar, who sells key chains, cool drinks and snacks out of a shack at the entrance to Dhanushkodi, says the nightmare of the 1964 cyclone almost came alive in 2004, when the tsunami struck the Tamil Nadu coast. “For a few minutes before the tsunami hit the coast, the sea receded more than 1,000 feet and we could see the remnants of several buildings. It barely lasted five minutes and the water rose up again. But luckily, the sea didn’t come charging in that year,” he says. The “structures” he saw were probably buildings the sea swallowed in 1964 and which remain tucked away in its innards.

Next to Kumar’s shop is a memorial for Neechal Kaali that displays the catamaran he used for more than seven decades as a fisherman.

Without a proper road and electricity, news rarely travels to Dhanushkodi. But Kumar is excited to share something he has heard — that the Centre recently sanctioned Rs 20 crore to rebuild the 5-km-long stretch connecting Mukundarayar Chathiram to Dhanushkodi. The National Highways Authority of India has already begun work from the Dhanushkodi end. Once ready, Dhanushkodi will again get connected to Rameswaram town and the mainland. “It took 50 years to rebuild a road that was washed off in the cyclone. Now I hope the train comes back,” he says.