Muzamil Jaleel is a Deputy Editor at The Indian Express and is widely recognized as one of India’s most authoritative voices on Jammu & Kashmir, national security, and internal affairs. With a career spanning over 30 years, he has provided definitive on-the-ground reportage from the heart of the Kashmir conflict, bearing witness to historic political transitions and constitutional shifts. Expertise and Investigative Depth Muzamil’s work is characterized by a rare combination of ground-level immersion and high-level constitutional analysis. His expertise includes: Conflict & Geopolitics: Decades of reporting on the evolution of the Kashmir conflict, the Indo-Pak peace process, and the socio-political dynamics of the Himalayan region. Constitutional Law: Deep-dive analysis of Article 370 and Article 35A, providing clarity on the legal and demographic implications of their abrogation in 2019. Human Rights & Accountability: A relentless investigator of state and non-state actors, uncovering systemic abuses including fake encounters and the custodial death of political workers. International War Reporting: Beyond South Asia, he provided on-the-spot coverage of the final, decisive phase of the Sri Lankan Civil War in 2009. Landmark Exposés & Impact Muzamil’s reporting has repeatedly forced institutional accountability and shaped national discourse: The Kashmir Sex Scandal (2006): His investigative series exposed a high-profile exploitation nexus involving top politicians, bureaucrats, and police officers, leading to the sacking and arrest of several senior officials. Fake Encounters: His reports blew the lid off cases where innocent civilians were passed off as "foreign terrorists" by security forces for gallantry awards. SIMI Investigations: He conducted a massive deep-dive into the arrests of SIMI members, using public records to show how innocuous religious gatherings were often labeled as incriminating activities by investigative agencies. The Amarnath Land Row: Provided critical context to the 2008 agitation that polarized the region and altered its political trajectory. Over the years, Muzamil has also covered 2002 Gujarat riots, Bhuj earthquake, assembly elections in Bihar for Indian Express. He has also reported the peace process in Northern Ireland, war in Sri Lanka and national elections in Pakistan for the paper. Awards and Fellowships His "Journalism of Courage" has been honored with the industry's most prestigious accolades: Four Ramnath Goenka Awards: Recognized for J&K Reportage (2007), On-the-Spot Reporting (2009), and Reporting on Politics and Government (2012, 2017). Kurt Schork Award: From Columbia University for international journalism. Sanskriti Award: For excellence in Indian journalism and literature. IFJ Tolerance Prize: For his empathetic and nuanced reporting in South Asia. International Fellowships: Served as a visiting scholar at UC Berkeley and worked with The Guardian, The Observer, and The Times in London. He has also received Chevening fellowship and a fellowship at the Institute of Social Studies, Hague, Netherlands. Professional Presence Current Location: New Delhi (formerly Bureau Chief, Srinagar). Education: Master’s in Journalism from Kashmir University. Social Media: Follow him for field insights and rigorous analysis on X (Twitter) @MuzamilJALEEL. ... Read More

- Tags:

- AFSPA

- Disturbed Areas Act

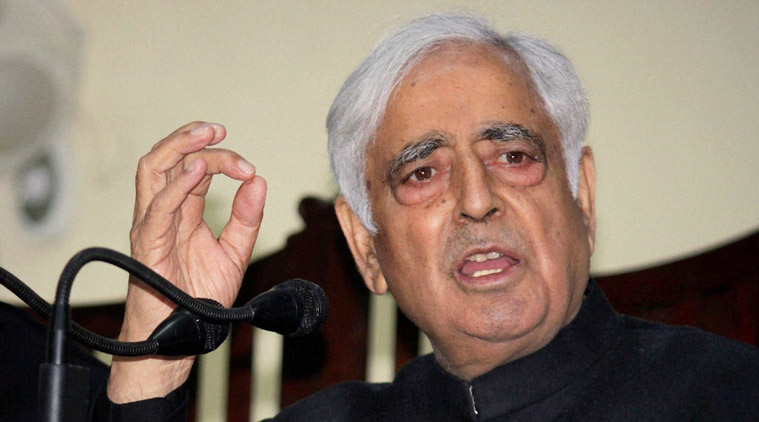

The Mufti government retorted that the power to declare an area disturbed was “inherent in AFSPA”.

The Mufti government retorted that the power to declare an area disturbed was “inherent in AFSPA”.