Leisure and livelihood: The sellers of Daryaganj book market

Daryaganj’s Sunday book market, a cultural icon since the 1960s, now at Mahila Haat, is hailed as a hub of resilience in Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar by Kanupriya Dhingra

Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar,' published by Cambridge University Press

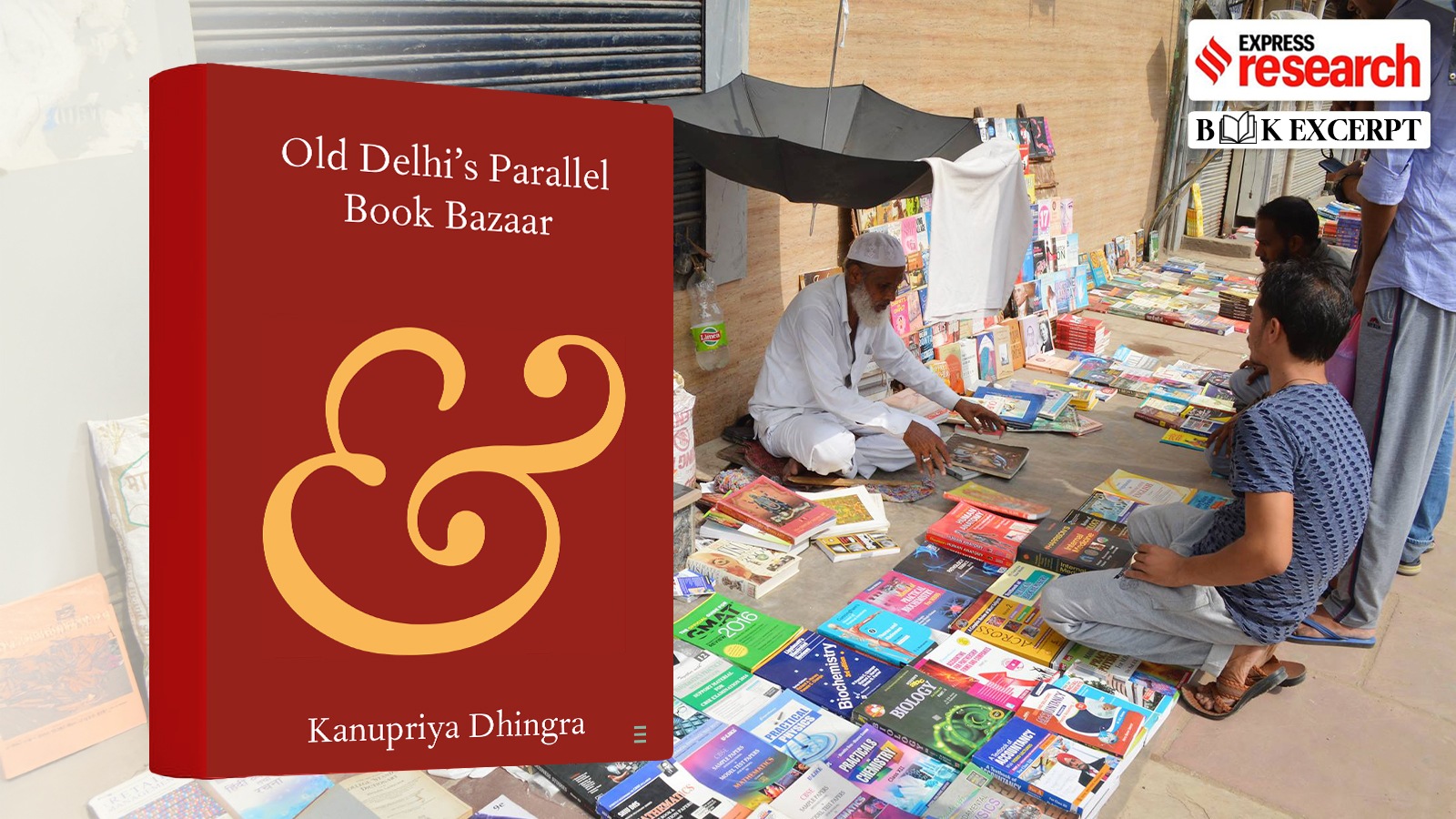

Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar,' published by Cambridge University PressImages of hordes of readers poring over books, periodicals, and magazines in Old Delhi’s Daryaganj on Sunday mornings represent the popular readership in the city. The iconic market, which shifted to Mahila Haat in 2019, is unique in the way it has functioned over the years. It came up in the 1960s as a natural market as both sellers and buyers came together to create the space almost organically — it was established without much infrastructural support.

Professor Kanupriya Dhingra, who has been studying the market’s historical development closely for the last several years, recently came out with her book on the subject, Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar’. Published by Cambridge University Press, Dhingra’s book looks at the Sunday book market, also known as the Daryaganj Sunday Patri Kitaab Bazaar, as “a parallel location for books and a site of resilience and possibilities.”

An excerpt from the book talks about the booksellers at the market and the unusual ways in which they have been sourcing their books and periodicals for generations. As Dhingra notes, this is not a profession per se, “you don’t study to become a street vendor”. However, her research also shows there is a training of a different kind which is required to learn exactly what would be most desired by the diverse groups of readers — from university students, and civil service aspirants, to the avid readers of the vernaculars among others.

Hobby Bhi Hai, Roti Bhi: The Vendors of Sunday Book Bazaar

While interviewing the booksellers, I asked each of them the same question: Aap meri kitab ke kirdar hain, mujhe apni kahani batayenge? (You are a character in my book, would you like to share your story with me?) I pursued these stories as they were narrated to me. Most sellers invited me to sit with them on their side of the bookstall to listen patiently. (Amidst several anecdotes, there were also bits of poetry, stories of love and loss, and quite a lot of tea and snacks.) As a book buyer, I had hitherto always been on the other side of the footpath. By shifting to the booksellers’ side, I experienced a shift in my gaze.

Choosing and Building Specialisation

Let us look at Abdul Wali’s journey into this profession, which will show how a vendor ‘arrives’ at the Patri Kitab Bazaar, gains knowledge, and makes decisions related to what circuit they want to continue in.

Around 1972, Parvez Kumar Rohilla was popular among the vendors of the Patri Kitab Bazaar for the effort he would put into collecting and curating individual ‘sheets’, extracted from fashion and beauty magazines, both imported and local. Wali remarked: ‘Professional aadmi the. Farrate se angrezi bolte the. Har Sunday red tie lagake aate the’ (‘He was a professional. Used to speak English fluently. Wore a red tie every Sunday’). He would go around the city all days of the week to middlemen (intermediaries) and houses around the city to collect the primary material from which he would make ‘files’ (folders) of such sheets. He would sell a single sheet of fashion designs at a fixed price of Rs. 4 for the Western content and Rs. 2 for Indian content. These books were originally priced at Rs. 300–400, which was quite expensive for students. Buying only relevant pages for a much lower price, instead of the whole text that may not be useful in its entirety, was a better option. He also sold old editions of magazines such as India Today and TIME magazine. Wali still has these ‘files’ and a good collection of these magazines, but he doesn’t sell them. There are no ‘current buyers’, says Wali. However, he is willing to wait for the right shauqeen buyer (Daryaganj afficionados), who would buy them from him at a higher value. Rohilla introduced Wali to the book business at Patri Kitab Bazaar. When he decided to quit, Rohilla asked Wali to acquire his stock. (Rohilla later started a matrimonial webpage, which, according to Wali, is doing quite well and gives Rohilla some much-needed rest.) However, Wali wasn’t quite willing; he found Rohilla’s mode of business exhausting and quite demanding. Hence, instead of dealing with fashion and beauty catalogues and old magazines, Wali entered the ‘study-material circuit’ to avoid ‘hardwork’: ‘Mehnat se bachne ke liye maine school line pakdi.’

Forty-five-year-old Abdul Wali now runs a bookstore in West Badarpur, Delhi-53, and his principal source of income is his stall and the clientele at the Patri Kitab Bazaar. Before entering the book business, Wali tried to study for the civil service entrance exams. He also studied Arabic at the Modern Indian Languages Department at the Arts Faculty, University of Delhi––he was told there was good demand for Arabic teachers in the Gulf countries. However, he realised that there was too much competition. Further, his poor financial situation prevented him from delaying the search for a steady source of income. Wali’s cautious yet strategic entrepreneurial attitude towards earning his livelihood in the early stages of his professional career extends towards how he pursues his business in the present day. He is not one to take risks.

“The bid (for imported books) starts at Rs. 100 at the transport auctions held at Gautampuri and Seelampuri. The stock is packed in sacks. Those who buy more get a discount (on the initial principal bidding amount). You can get it for as little as Rs. 40 per kilo. Qamar bhai takes many risks. He buys the whole stock in the auction whenever the import containers arrive. He is considered a ‘king’. That is why he gets the biggest discounts too. I don’t do this. I sort books. I buy select stock at the price of Rs. 100 to Rs. 200 per kilo. It is somewhat necessary! For instance, if I buy a stock of medical books, which is also ‘study material’, I don’t have the required specialised knowledge of editions and content. If the material is old, it will cause me loss. I have always worked with the study material that is relevant to colleges. So, that is what I buy. I don’t take risks, so I buy less from auctions and more from paper merchants. Along with less risk and loss of profits, less hard work and labour are involved. Qamar ji has huge storage units; I don’t. I only buy whatever I can store. I build my clientele here instead. If you sell good, useful material to one student, they come.”

Wali’s escape from ‘a lot of hard work’ doesn’t mean his business is easy-going. It took skill, management, and knowledge to build the stock and the clientele that he now has. He has his own mechanisms for acquiring books. At the same time, he knows how to limit his stock: he doesn’t try to get into unnecessary competition with older vendors who also have more experience and bigger spaces where they can store books. Further, even within the study-material circuit, he has limited himself to a certain kind of study material: he started his business by selling schoolbooks but has shifted to selling low-priced guidebooks or kunjis and second-hand coursebooks for the students of Delhi University, Ambedkar University, and Jamia Millia Islamia. He avoids buying just any form of course material: he mentions medical books as a particular exception since this involves extensive knowledge of relevant editions and familiarity with the needs of a specific community of students. He tells me that there is also enough competition in his line of business. As soon as the vendors of this circuit get information on any second-hand stock availability at a paper market or with any individual kabadiwallah, they rush to acquire it: ‘Wo bees minute kehta hai to hum das minute mein pahonch jaate hain’ (‘If [the paper merchant] says twenty minutes, we get there in ten minutes’). In the present day, a scrap dealer buys his stock from houses and private and public libraries at a rate of Rs. 8–10 per kilo or for free at times. Booksellers sort useful material from the scrap and buy it from the scrap dealers at around Rs. 40 per kilo: (‘Jab maine business shuru kiya tha, tab parents koi bhi books le lete the. R. D. Sharma chahiye hogi, to Manjit Singh bhi chal jaati thi. Ab school chabi bharta hai. R. D. Sharma boli hai to wahi lenge’ (‘Around the time I started my business [as a vendor of school-books], parents would buy any editions. They won’t mind a Manjit Singh or an R.D. Sharma [authors of popular companion books on mathematics]. Now, the schools tell the students what to buy. If they’ve been asked to buy an R. D. Sharma, they’ll not buy anything else’).

‘Patri Ne Sikhaya’: Circumstantial and Experiential Knowledge

The diversity of sources and the active methods used to acquire books are key factors that influence vendors in determining their specialisation. At the point in the chronology of the bazaar’s history at which a vendor joins the Patri Kitab Bazaar, diverse sources are being sought by the existing vendors. Even when the first few vendors decided to sell books at Daryaganj, they had fixed sources they could rely on: imported second-hand books, paper markets, private collections, libraries, and railway auctions. Magazines and novels were among the first ‘books’ to arrive at this patri. Since then, the books that the vendors of Daryaganj sell have arrived from alternative sources, and not in the ways that ‘proper’ book vendors acquire books to be sold in their bookshops. Selling books at the Patri Kitab Bazaar is a crossover between street vending and proper bookselling. That is, not only does the vendor have to know how to sell books and have a sense of the ‘commodity’ they are selling, but they also need to be aware of the ways in which bazaars operate. It’s not a profession per se: you don’t study to become a street vendor, therefore it’s not an obvious career choice.

However, there is training required. The seven Kumar brothers are all in the same business, but each deals with a different genre of books. Having started with general books, they each specialised their stock over time: medical books, art books, syllabus books, novels, or books for competitive exams. This also allows the brothers to keep their businesses separate from each other. Further, their decision to diversify their businesses into different circuits can be considered a strategic move. They can reinforce certain power dynamics and hierarchy in the market by absorbing and producing knowledge of most of the mechanisms that have governed the bazaar.

The Kumar brothers now also have a bookshop and a printing press in Nai Sarak, where they repair some second-hand books to sell at the bazaar. Their extended book business is rooted in the experience at the Patri Kitab Bazaar: ‘Ye bahot purani baatein hain’ (‘These are very old matters’), says Sushil Kumar, recounting the purane din, old days. Out of the seven brothers, Sushil Kumar was the first one to start selling books: ‘Sabse pehle maine hi yahaan kitab bechna shuru kiya. Ek aane ki ek kitab bechte the. Jahaan khali jagah dikhti thi, waheen baith jaate the’ (‘I was the first one to start selling books here. I used to sell one book for a penny. I would sit down wherever I found an empty space’). Initially, he would sell books for one anna each. In those days, vendors would sit anywhere they liked since there were not so many of them, and there was no need for external or internal regulation. Their father bought stocks of books, and the brothers were supposed to sell them. Over the years that followed, they began travelling across the country to gather books– something that quite a few booksellers do not do, as they depend on local sources.

Bookseller Niyazuddin tells me that he has never moved away from the traditional sources: local libraries and private collections. He travels either on public transport or on his scooter. As a result, his collection is not specialised since he has not put in the effort to curate or define a collection. He sells whatever he gets. Even though he started around the same time as Sushil Kumar, he remained modest about how he wanted to operate in the bazaar. Niyazuddin’s case is an important exception––unlike what we have seen with the Kumar brothers or Abdul Wali, specialisation is not a necessary condition that defines the present-day traditional vendor.

The way a vendor acquired their training, combined with how they started their business at the bazaar and decided to lead the business in the future, is one way to classify the vendors of Daryaganj. Mahesh, whom we met earlier, started with miscellaneous stock based on whatever was available. He now sells books for competitive exams: IELTS, TOEFL, GRE, GMAT, and so forth. Mahesh’s knowledge of bookselling is only partially due to the training he received from his ustad; the rest is from his experience on these streets––that is, a combination of training and circumstantial knowledge, as is true for various older vendors. Mahesh tells me ‘Main bahot saari bhasha parh leta hoon. Bol nahin sakta, par dekh kar yeh bata dunga ke yeh kaunsi bhasha hai’ (‘I can read multiple languages. I cannot speak in those many languages, but I can identify which language it is just by looking at it’). When I asked what languages he can read fluently, he told me he understands Dutch, German, Sanskrit, Spanish, and what he calls ‘American’. Mahesh justifies his claim to be a polyglot based on his profession: ‘Patri se sikha hai, madam’ (‘I learnt it on the streets, Madam’). I asked him how: ‘Anparh ko angrez ke beech mein chhor do wo bhi angrezi bolega’ (‘Leave an illiterate amidst English-speaking people, and he will speak in English’). With time, Mahesh gained familiarity with his stock, and, corresponding to the demand for books, his ‘knowledge’ about his commodity increased. Students asked him about titles in different languages. By comparing those titles with his own, he figured out how to tell which language they were in.

Like several of the vendors, Mahesh doesn’t read the books he sells or has meagre information about their literary value: the value of books, for Mahesh, is limited to their titles, language, and how often his customers demand them. Those who followed Mahesh into the profession then adopted these skills. His knowledge, gained from a combination of training, experience, and chance, has become part of an informal, unofficial, and important repertoire for a new vendor who wants to sell the same stock. This is how Mahesh belongs to what I understand as the traditional community of vendors at Daryaganj Sunday Book Market.

Each of these vendor’s trajectories, then, demonstrates how the parallel business of book vending at the bazaar is related to the subsistence economy. It is informal, unprotected, and involves more risks than the ‘proper’ bookselling business.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05