© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

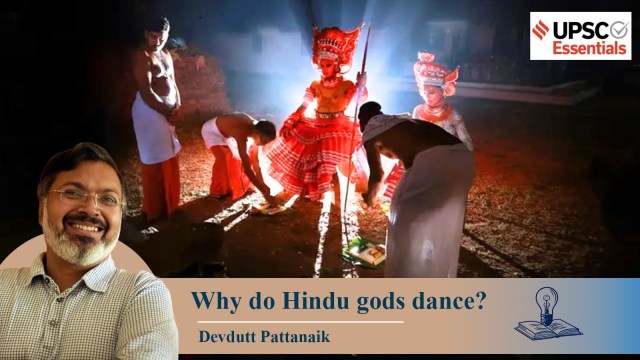

Kerala's Theyyam, loosely translated to ‘dance of the gods’, is celebrated as a medium of access (to the gods on earth) and protest (against the caste system). (Source: Manu Mayyil)

Kerala's Theyyam, loosely translated to ‘dance of the gods’, is celebrated as a medium of access (to the gods on earth) and protest (against the caste system). (Source: Manu Mayyil)(The Indian Express has launched a new series of articles for UPSC aspirants written by seasoned writers and scholars on issues and concepts spanning History, Polity, International Relations, Art, Culture and Heritage, Environment, Geography, Science and Technology, and so on. Read and reflect with subject experts and boost your chance of cracking the much-coveted UPSC CSE. In the following article, Devdutt Pattanaik, a renowned writer who specialises in mythology and culture, explores diverse forms of dance across India in a broad stroke, capturing its multifaceted expressions of human creativity, rituals, cultures and identities.)

Dance is an integral part of culture. It cannot be captured in a museum — except as photographs or videos. But as a performance, it is something that changes with time and space. Therefore, like music, it is an intangible heritage.

Hindu temple art shows gods dancing – Shiva dancing, Krishna dancing, Ganesha dancing. The dance of devadasi is how gods were entertained in temples. But we will never see images of Buddha dancing, the Tirthankaras dancing, the Islamic prophets dancing. In fact, dance is haram in orthodox Muslim traditions while in mystical traditions of Sufism, and the bhakti movement, dance is a tool to experience the divine.

In Europe, dance was linked to paganism and rejected by Christianity. Dance thus reveals the ideology of different faiths, different communities, and different tribes. For Hindus, it represented worldliness. For Buddhists, it represents temptation. Monotheistic faiths associated it with idolatry.

Evidence of Indian dance comes from ancient times. The earliest is the ‘wizard dance’ of Bhimbetka caves in Central India, where people wearing horns are seen dancing. This belongs to the Stone Age. In Harappa we see seals of seven people, dressed in the same clothes, dancing around a tree. It is an indicator of a form of tribal dance. Like in the Bhimbetka caves, the dancers wear horns.

In the Vedas, dance is not discussed as much as music — remember Vedas as “shruti”, to be heard. Sama Veda gave melodies to the hymns of Rig Veda. Yajur Veda introduces the idea of mudra (gestures) during ceremonies. This is said to have been the origin of dance.

Later, dance and song were used as entertainment during Vedic ceremonies to tell stories related to ancient kings, sages and gods.

Sculptures from the Mauryan period (321–185 BCE) at sites like Sanchi, Barhut, and Amaravati include representations of dancers. Similarly, Greek dancers in Gandharan Buddhist art imitate the followers of Bacchus/Dionysus (the Greek god of wine and ecstasy). By the Gupta period, terms like “nritya” (expressive dance) and “nataka” (drama) appeared with Bharata Muni’s Natyashastra emerging as the classical treatise on the performing arts.

In the heavens, this was the domain of apsaras (celestial dancers). On earth, this was done by ganikas (courtesans). The dance manuals in classical texts such as the Natyashastra speak of abhinaya (expressions), mudra (gestures), and angika (postures). Movements follow the rules of geometry. There is much in dance to indicate it was the forerunner of yogic asanas (yoga postures).

Sanskrit plays, and Puranic stories, refer to a dance competition between gods, apsaras and royal dancers. In Tamil temple lore, Shiva competes with Shakti in a dance competition, and wins by raising a leg which the goddess is too shy to do. Then there is the story of how Bhasmasura is asked by Mohini to dance with her. By following her movements, Bhasmasura touches his head and is reduced to ash.

Islam forbids dance. But Mughals who married Rajput women encouraged the tawaifs (courtesans) to perform in their courts. Thus dance was patronised in royal courts, reminding one of the dancing halls of temples, as well as the dance performed in the heavenly court of Indra. These dances continue even today in Bollywood films.

Shastra means a subject that is well documented, with details classified. Classical dance is a shastra because it has a long history, is documented in some formats and requires training to perform as well as appreciate it. India has eight classical dance forms, each with distinct styles and origins.

Kathakali and Mohiniattam are theatrical and performative. Bharatanatyam, characterised by its geometric and angular movements, is a modern refined version of the temple dances of the Devadasis. Kuchipudi dancers often dance on plates while Odissi is more soft and fluid, with the tribhanga pose — where the body bends in opposite directions at the neck, hips, and knees.

Then, we have Manipuri dance, which is rooted in the Vaishnava faith of the Meiteis, or people of the Manipur valley, and Sattriya from Assam, the last dance form to be given classical status. In the North, we only have Kathak as a notified classical dance form, which was performed first in temples, and then in courts.

Chhau, a masculine, almost military, dance form, is performed in Bengal, Odisha, and Jharkhand. Masks are an integral part of Purulia Chhau in Bengal and Jharkhand. In Odisha, masks are not worn. Although Chhau is not as refined as the classical dance forms, some consider it classical. However, this folk-classical distinction is a contentious issue and annoys many people.

Sometimes folk performances are also linked with rituals, like Karnataka’s Bhoota Kola or Kerala’s Theyyam. These performances reflect subaltern traditions, showcasing how they communicate with gods and relate to nature. In Ladakh and Shillong, one finds masked dancers enacting stories of Buddhist siddhas defeating demons and taming angry spirits.

The aim of folk dance is also to unite the community through synchronised dance with simple steps and a basic percussive beat. In tribal communities, dance is usually collective rather than individual. This gave rise to harvest rituals, like the Bihu dance of Assam, typically performed during harvest.

The tribes of the Northeast have many unique dances that symbolise their unique identity. Dance such as nautanki and lavani are meant for the entertainment of the masses. Thus dance can be a vehicle for politics, philosophy, festivals, rituals, identity, and entertainment.

What types of dance competitions are mentioned in Sanskrit plays and Puranic stories?

In Tamil temple lore, how does Shiva win the dance competition against Shakti?

Which Veda introduces the idea of mudra (gestures), and in what context?

How are folk performances like Bhoota Kola in Karnataka and Theyyam in Kerala connected to rituals and subaltern traditions?

How can dance serve as a medium for politics, philosophy, festivals, rituals, identity, and entertainment?

(Devdutt Pattanaik is a renowned mythologist who writes on art, culture and heritage.)

Share your thoughts and ideas on UPSC Special articles with ashiya.parveen@indianexpress.com.

Subscribe to our UPSC newsletter and stay updated with the news cues from the past week.

Stay updated with the latest UPSC articles by joining our Telegram channel – IndianExpress UPSC Hub, and follow us on Instagram and X.

Read UPSC Magazine