© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

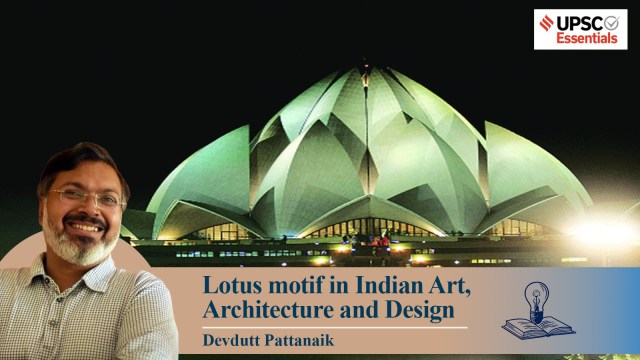

The Bahai House of Worship in Delhi, completed in 1986, takes the form of a half-open lotus with twenty seven marble petals. (Source: Express Archive)

The Bahai House of Worship in Delhi, completed in 1986, takes the form of a half-open lotus with twenty seven marble petals. (Source: Express Archive)The lotus today is a symbol of a leading political party in India, but for thousands of years it has been part of Indian myth, ritual, architecture, and craft. At the village level, the lotus thrives as a simple floor drawing made with rice flour. Such images can be traced back to prehistoric cave art, where humans first tried to map the natural world through symbols.

The lotus does not appear in Harappan art. It entered the visual vocabulary of the subcontinent only in the 3rd century BCE, when Ashokan pillars rose across the Mauryan Empire – each carved from a single block of polished sandstone with a lotus capital. The flower becomes the base from which lions, bulls, elephants, and horses proclaim royal authority. It marks the moment when the lotus steps into Indian statecraft.

Buddhist monuments continue the story. Between 100 BCE and 100 CE, stupas at Sanchi, Bharhut, and Amravati display lotus medallions on their railings. Their reliefs show lotus ponds, yaksha with potbellied abundance, and yakshi with forest grace.

The earliest known image of Lakshmi seated on a lotus, flanked by elephants, appears here, hinting at a shared sacred vocabulary across traditions. Bodhisattvas and goddesses like Tara of later Buddhism are all holding lotus flowers or seated on lotus flowers. Jain goddess Padmavati, yakshi of Parsvanatha, is shown seated on a lotus.

By 500 CE, Hindu temples emerged with the lotus embedded in their design logic. Temple plans follow lotus diagrams. Platforms rise like giant petals lifting the sanctum toward the sky, as seen in the sun temple of Modhera in Gujarat, located on the Tropic of Cancer.

Capitals of pillars bloom upward or downward. Ceilings are often inverted lotuses. Outer walls show gods and humans holding lotus buds. The sun god carries lotuses in both hands. Lakshmi remains seated on her flower throne. Domes and towers evoke the cosmic lotus of Mount Meru, as in Angkor Wat or the lotus pavilions of Hampi.

When Indo-Islamic architecture rises after the thirteenth century, the lotus adapts to new aesthetics. Mosques favor geometry over naturalistic forms, yet the Indian lotus enters the vocabulary with ease. Domes swell into lotus bud shapes. Bases of domes reveal carved petals, while the top features inverted lotus forms.

This is visible at Humayun’s tomb and the Taj Mahal. Lotus buds line arches, a feature first seen in the Alai Darwaza. The motif decorates balconies, walls, and floors, often through inlay work. Gardens such as Babur’s Bagh-e-Nilufar are designed for growing lotuses and lilies. Fountains take lotus shapes. Even Akbar’s throne at Fatehpur Sikri sits on a lotus, blending imperial might with native symbolism.

Sikh gurudwaras adopt similar imagery. The dome of the Golden Temple evokes a half-open lotus, and lotus patterns adorn gates and windows. In the Guru Granth Sahib, the flower becomes a metaphor for a mind untouched by desire, just as the ancient Upanishads once described.

Modern India continues the tradition. The Bahai House of Worship in Delhi, completed in 1986, takes the form of a half-open lotus with twenty seven marble petals. Its nine entrances open to a central hall that welcomes all, matching the flower’s association with purity and inclusion.

Tantrik geometry turns the lotus into a cosmic diagram. Two criss-crossing squares produce an eight petalled lotus, while two interlocked triangles produce six petals. Each represents the womb of creation. Human anatomy becomes a tower of lotuses known as chakras. Texts map seven principal lotuses along the spine, from the four petal lotus at the base to the thousand petal lotus at the crown, where matter dissolves into spirit.

Dance manuals describe lotus mudras shaped like budding or blooming flowers. Yogic practice transforms the body into a lotus through padma-asana, a posture linked with deep meditation. Images of Buddha, Shiva, and Jain Tirthankaras seated in this pose reinforce the link between (physical) balance and (spiritual) awakening.

A silk panel from eastern India dated to the sixteenth century shows concentric rings of lotus petals. Phulkari of Punjab, kantha of Bengal, ikat of Odisha, kasuti of Karnataka, and paithani of Maharashtra each place the lotus at the heart of their designs.

Lotus also has a mark on textile arts. A silk panel from eastern India, dated to the sixteenth century, shows concentric rings of lotus petals. Phulkari of Punjab, kantha of Bengal, ikat of Odisha, kasuti of Karnataka, and paithani of Maharashtra – each place the lotus at the heart of their designs.

Across centuries, the lotus remains India’s simplest yet most profound symbol, inviting every generation to look beyond the surface and seek the hidden spring from which life unfolds.

When did the lotus enter the visual vocabulary of the Indian subcontinent, and how is this linked to the rise of the Ashokan pillars in the 3rd century BCE?

Discuss the symbolic and architectural roles of the lotus in temple design, from ground plans to superstructures, with reference to temples such as Modhera in Gujarat.

Mosques favour geometry over naturalistic forms, yet the Indian lotus enters the vocabulary with ease. Illustrate with examples from Mughal monuments.

Examine the concept of the lotus as the ‘womb of creation’ in Tantric philosophy, with reference to geometric symbolism.

Trace the evolution and symbolism of the lotus motif in Indian textile arts from the medieval period onwards, with reference to the sixteenth-century silk panel from eastern India.

(Devdutt Pattanaik is a renowned mythologist who writes on art, culture and heritage.)

Share your thoughts and ideas on UPSC Special articles with ashiya.parveen@indianexpress.com.

Click Here to read the UPSC Essentials magazine for November 2025. Subscribe to our UPSC newsletter and stay updated with the news cues from the past week.

Stay updated with the latest UPSC articles by joining our Telegram channel – IndianExpress UPSC Hub, and follow us on Instagram and X.

Read UPSC Magazine