Venus may not have lightning after all, suggest study

Scientists have debated about the existence of lightning on Venus for nearly four decades. A new study seems to have settled that debate once and for all.

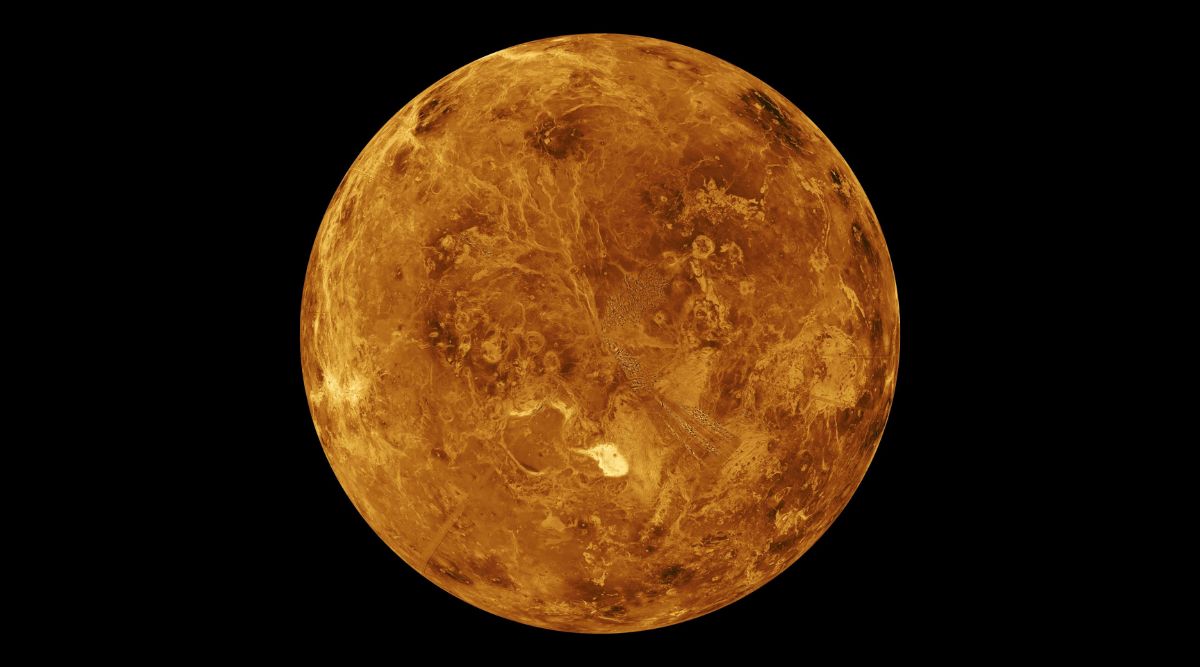

The northern hemisphere of Venus as seen by NASA's Magellan spacecraft. (JPL)

The northern hemisphere of Venus as seen by NASA's Magellan spacecraft. (JPL) Venus is an extremely inhospitable planet. It has a thick atmosphere whose greenhouse effect makes it the hottest planet in the solar system. Temperatures there hover around 475 degrees Celsius, hot enough to melt lead. But a new study suggests that it may be a slightly less dangerous place than we once thought.

Apart from its searing temperatures and crushing atmospheric pressure, it was a long held scientific belief that there could also be constant strobes of lightning on the unsavoury planet named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty. But a new study published last week in the journal Geophysical Review Letters suggests that this “lightning” may not be lightning at all.

To study the extreme environment of this distant world, scientists turned to a mission that was not designed to study Venus at all — NASA’s Parker Solar Probe.

The probe flew nearly 2,500 kilometres away from Venus in February 2021, according to the University of Colorado Boulder. At the time, Parker’s instruments picked up many signals of what are called “whistler waves.” On Earth, these waves can be kicked off by bolts of lightning. The researchers looked at the data and discovered that these whistler waves may not be from lightning, but instead, they could be from disturbances in the weak magnetic fields of the planet.

Based on signals that different scientific instruments have collected over time, it seemed like Venus’s atmosphere was riddled with lightning, but a lot of evidence that has come up in recent years speaks to the contrary.

Another study published in the journal JGR Planets this year suggested that the burning up of meteors in Venus’s atmosphere may have been mistaken as bolts of lightning for years. The latest study also concurs with a study published in 2021, shortly after the Parker flyby, which says the probe failed to detect radio waves generated by lightning on the planet.