At a party in Chennai one evening nearly a decade ago, a discussion between Moin S P M and Srinath Ravichandran shifted to a shared passion — rockets. “Won’t it be cool to build one?” Moin recalls telling his friend excitedly.

That audacious question turned into reality in 2024 when their company, AgniKul Cosmos, launched its first sub-orbital test vehicle powered by the world’s first single-piece 3D-printed rocket engine. At 7.15 am on May 30, Agnibaan SOrTeD (Sub-Orbital Technology Demonstrator) lifted off from a private launchpad the company had set up in Sriharikota (while the rocket lifts-off in a sub-orbital launch, it does not reach the height where it can successfully insert a satellite in an orbit). Engine parts are typically manufactured separately and assembled. However, 3D printing is likely to lower both launch costs and vehicle assembly time. With 3D printed engines, Moin said, putting together the launch vehicle will likely take only a couple of weeks.

Agnibaan SOrTeD. (AgnikulCosmos)

Agnibaan SOrTeD. (AgnikulCosmos)

Different cities, career paths

Though the friends, who grew up playing cricket together in Chennai, founded AgniKul in 2017, their paths took a while to converge since Moin, 34, and Ravichandran, 39, specialised in different streams. While Moin did aerospace engineering from Anna University in Chennai and an MBA in the field from the University of Newcastle, Ravichandran studied electrical engineering from College of Engineering in Chennai, followed by a certificate course in aeronautical engineering from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and a master’s degree in the same field from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Even the career paths they chose early on were quite different: Moin and his cousins set up a company that manufactured and sold fragrances and aromatic compounds, Ravichandran started working on Wall Street in New York, before shifting to Los Angeles.

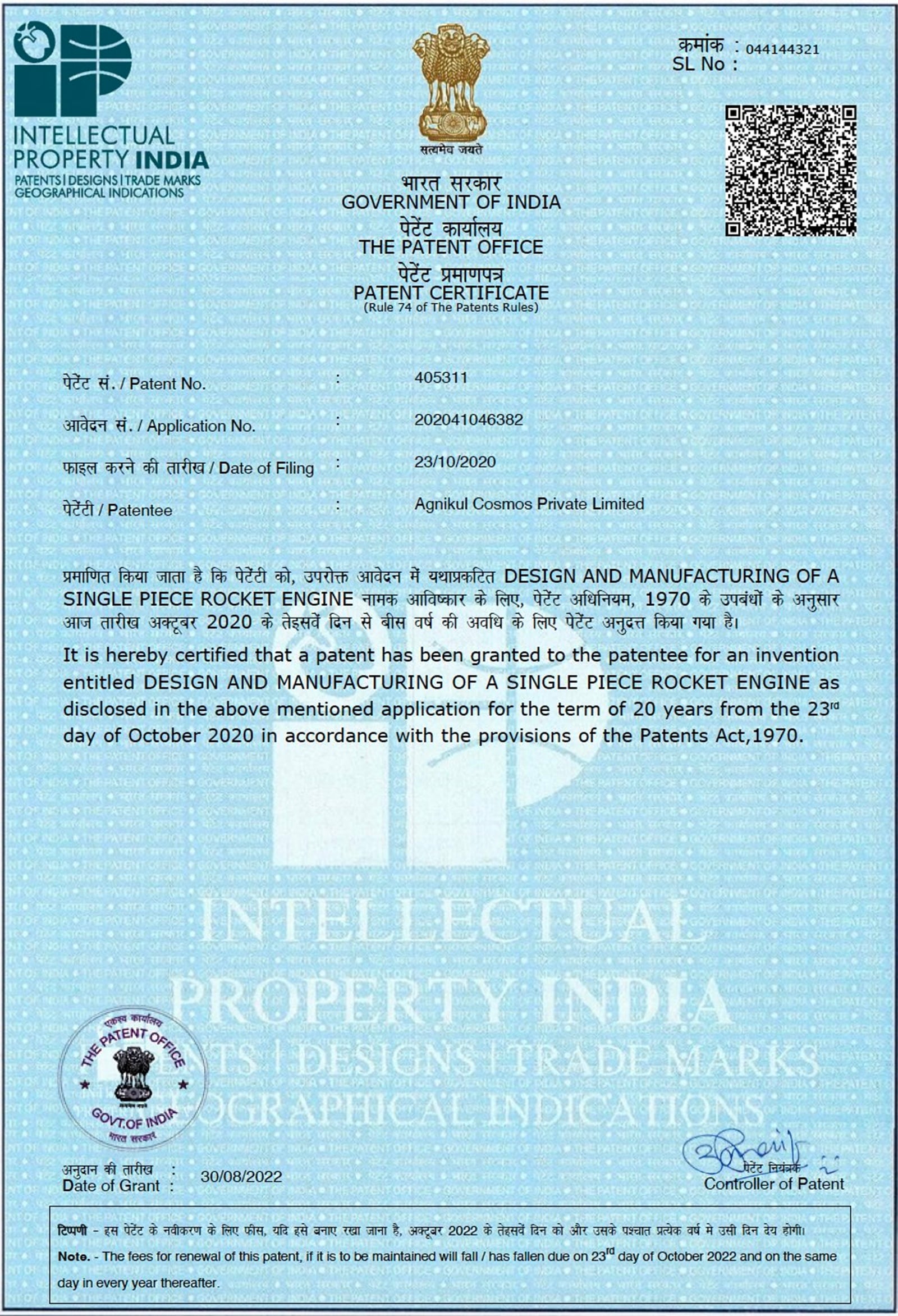

The patent certificate granted to AgniKul Cosmos for 3-D printing the world’s first single-piece rocket engine. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

The patent certificate granted to AgniKul Cosmos for 3-D printing the world’s first single-piece rocket engine. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

Speaking to The Indian Express via a video call from Chennai, Moin said, “The fragrance company was doing well. In fact, we were even exporting them, but I was starting to wonder what I was doing there. Ravichandran was feeling the same in the United States. Both of us felt the need to do something else.” The childhood friends then decided to set up a company, reach out to experts in the field and do something that had never been done before.“We knew 3D printing had been used to make smaller rocket parts. So why not the whole engine, we thought. Since it wasn’t possible to 3D print conventional designs, which are not compatible with 3D printers, the entire engine had to be redesigned,” Moin said.

The world’s first single-piece 3D-printed rocket engine by AgniKul Cosmos. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

The world’s first single-piece 3D-printed rocket engine by AgniKul Cosmos. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

Despite the audacity of their idea, Moin and Ravichandran still had to find someone who would help them “print” rocket engines and launch projectiles into space. “We needed people with experience in building rockets from scratch, and funds. Unlike Elon Musk (an investor in space company SpaceX, automotive company Tesla and social media platform X), we did not have millions to put into our company. Initially, the company was funded by us. Then, we met Prof Satya Chakravarthy (head of National Centre for Combustion Research and Development at Indian Institute of Technology-Madras). When he heard our pitch, his first question was: ‘Why haven’t you done it yet?’. He put us in touch with R V Perumal (the retired GSLV project director), who has seen the development of ISRO’s GSLV (geosynchronous satellite launch vehicle) from the start,” added the AgniKul co-founder.

Prof Chakravarthy and Perumal ended up becoming founding advisors in their company, which finally incorporated in 2017. “Since no launch vehicle companies were being set up, the process took a while. Although we did not know whether the government would liberalise the sector at that point, it was the direction in which that major spacefaring countries had gone in. That alone made us hopeful. With India being a spacefaring nation for years and demonstrating reliable launches over and over again, there is a level of confidence in Indian start-ups at the global stage now. And we are riding on their successes,” said Moin.

Story continues below this ad

Patented technology and faster turnaround time While AgniKul’s engine design is patented technology — “and not many details can be revealed” — Moin said there were certain parameters they had to keep in mind while designing the rocket, including the powder residue left behind due to 3D printing. “It was important to develop the ability to remove the powder residue to ensure there was no clogging inside the engine,” he said.

A bigger challenge was the build volume — the maximum size of a component that a 3D printer could make — off commercially available printers. “At that time, the maximum build volume of 3D printers was 400 mm x 400 mm x 400 mm. Today, there are printers with a build volume of 1 metre, making it possible to print larger rocket engines,” said Moin.

AgniKul currently has one 3D printer, but is looking to scale up keeping in mind the large market for small satellite launch vehicles. The bigger printers, it hopes, will also allow it to print the “nozzle skirt”, which is currently added after engine manufacturing, along with the engine.

On May 30, Agnibaan SOrTeD lifted off from the company’s private launchpad in Sriharikota. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

On May 30, Agnibaan SOrTeD lifted off from the company’s private launchpad in Sriharikota. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

There are significant benefits to 3D printing a rocket. Since the engine does not have moving parts — there are no joints, no welding and no fusing — the time taken to assemble a rocket is cut down significantly. When it comes to building the rocket, Moin says, there is additive manufacturing (or 3D printing) that takes about three days against conventional manufacturing, which takes nearly two weeks. Putting together a conventional rocket and testing it before the launch takes about nine months. He added that with 3D printed engines, putting together the launch vehicle will likely take only a couple of weeks. “The fast turnaround time of 3D-printing promises is in line with the ethos of start-ups,” he says.

Story continues below this ad

With significant mismatch in demand and supply when it comes to small satellite launches — and ISRO commercialising the Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV) and space-tech company Skyroot Aerospace set to start commercial launches — India is likely to capture a significant proportion of the market share, says Moin. “India can capture 15-20% of this market share in the next five years,” he says.

The company aims to conduct its first orbital launch and carry satellites to an orbit around the Earth by the end of the financial year. “We plan to begin commercial launches within nine to 12 months, and scale up to about 50 launches in a year,” said Moin.

He added that launches will take place from its existing launchpad at the Sriharikota spaceport and later from the upcoming port meant for small vehicles at Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu.

Agnibaan SOrTeD. (AgnikulCosmos)

Agnibaan SOrTeD. (AgnikulCosmos) The patent certificate granted to AgniKul Cosmos for 3-D printing the world’s first single-piece rocket engine. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

The patent certificate granted to AgniKul Cosmos for 3-D printing the world’s first single-piece rocket engine. (X/AgnikulCosmos) The world’s first single-piece 3D-printed rocket engine by AgniKul Cosmos. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

The world’s first single-piece 3D-printed rocket engine by AgniKul Cosmos. (X/AgnikulCosmos) On May 30, Agnibaan SOrTeD lifted off from the company’s private launchpad in Sriharikota. (X/AgnikulCosmos)

On May 30, Agnibaan SOrTeD lifted off from the company’s private launchpad in Sriharikota. (X/AgnikulCosmos)