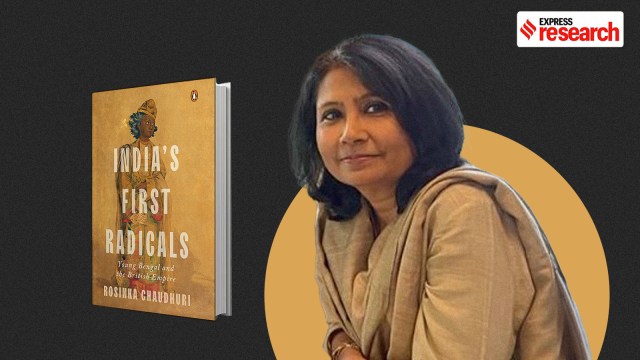

This goes back to the time when I submitted my thesis for the DPhil degree at Oxford. As I had little to do, my supervisor, Robert Young, asked me to help him locate a book on Young Bengal for one of his ongoing research projects. I went to the now-vanished India Institute Library in the New Bodleian at Oxford, where all India-related materials were housed. After a whole day at the library, I realised that there was no book on Young Bengal. 10 years later, working on a complete edition of poet Henry Derozio, I collected additional material on the group. It took me another decade to organise my thoughts and many visits to the British Library for a lot of archival research before I figured out how to structure India’s First Radicals.

Speaking of the name Young Bengal, were age, gender, and class defining features of this group?

Story continues below this ad

Yes, age is a crucial factor in the extreme rebelliousness of this group. In that sense, they were indeed India’s first radicals. The term ‘radical’ often denotes extreme positions, and they did take up very extreme positions in their youth. As for gender, it is missing here in the form of women protagonists because, of course, in the 1830s and 40s, there were no women in the public sphere, although this was the first group to speak loudly and consistently against gender discrimination. They were also the first to speak vehemently against caste discrimination and against what they called ‘Brahmincraft’. As for class, there has been a misconception about the people designated Young Bengal — that they belonged to the elites simply because they were students at Hindu College. The group of friends I deal with (in the book) are the first batch of Hindu College and direct students of Derozio. I decided to focus on a number of important developments in the year 1843 with regard to their activities that have not been discussed so far in any detail.

Ironically, many of them were scholarship students. For instance, Radhanath Sikdar (1813–1870), who later headed the team that calculated the height of Mount Everest, came from a poor household. The same was true for Ramgopal Ghose (1815–1868), whose father was a shopkeeper in colonial Calcutta and couldn’t afford to support his son’s education at Hindu College. However, David Hare helped fund Ghose’s education. There were also figures like Peary Chand Mitra (1814–1833), who came from a family of banias — not fabulously wealthy but still well-off — and Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee, who belonged to the Tagore family. So, it was a mixed composition, although all male.

You describe them as ‘India’s First Radicals’ while cautioning against labeling them as nationalists. How would you best describe their agenda?

The reason I say it would be a mistake to call them ‘nationalists’ is because the notion of nation and nationalism developed later. It emerged in the second half of the 19th century. The period of Young Bengal I deal with falls in the first half, from 1831 to 1843, with the book focusing on 1843, when they were young men of action, not just students straight out of the Hindu College but mature professionals who wanted to work for the good of the country. Neither ‘nation’ nor ‘national’ had yet become buzzwords in the way they would become from the 1860s onwards.

Story continues below this ad

This was also a group that was internationalist in its thinking. They didn’t view the cause as something that excluded other communities, such as mixed-race individuals or even sympathetic Englishmen, who joined them in forming what I argue to be the first Indian political party in April 1843.

How did Young Bengal differ from the revolutionary terrorism that later sprouted in Bengal?

Revolutionary terrorism in Bengal, also led by radicals, emerged in the 1920s and 30s. Young Bengal arose a century before that. While they were inspired by the armed revolts of the peasant leader Titumir (1782-1831), they were in a moment of fluidity, holding the belief that, somehow, constitutional reform through legislation and the courts would work for the betterment of the rights of Indians — a belief that lasted throughout the nineteenth century.

The important shift in Indian political thought that they mark is represented by their realisation of the uselessness of sending petitions to the British Parliament as was the norm till then. Petitions were a cumbersome process — one needed an agent to approach a British Member of Parliament, who would be paid to raise a question in Parliament. So, Young Bengal wondered: why not shift public opinion in Britain itself, which would then influence Parliamentary legislation on India? This is why they invited the British orator and celebrity abolitionist George Thomson, who had helped achieve the Slavery Emancipation Act in 1833, to Calcutta in 1843. He would spend a year in Calcutta, working with Young Bengal to understand their socio-political goals.

Story continues below this ad

Did the activities of Young Bengal lead to any significant legislative changes?

No, it had no legislative impact. This is also why generations of historians have simply shrugged and asked, “What did they achieve?” I have argued in the book that it would be a mistake to say that, for two decades, the kind of discussions taking place in civil society — through political forums, newsprint, journals, and magazines — achieved nothing. For the first time, a certain modern grammar and rhetoric of protest and an understanding of the rights of Indians and the duties of good governance were put into place.

Members such as Peary Chand Mitra wrote on the unfair land regulation acts that threw traditional tenants off their land, Dakshinaranjan argued against the corruption in the police and judiciary and for the liberty to free speech, and Radhanath Sikdar, for instance, fought a case against the British magistrate of Dehradun for abusing Indian coolies. Although he lost the case, was fined, and was punished in the process, what is significant is that a new way of thinking emerged in relation to the colonial presence — that we, as Indians, are equal to you, as men.

They founded the first Indian political party, the Bengal British India Society (1843), although it lasted only three years. They were also the first group to think about constitutional reform. However, what is typically mentioned in our history books when studying 19th-century nationalism is the work of figures like Dadabhai Naoroji and Surendranath Banerjee, who were active in the late 19th century.

Story continues below this ad

Did Young Bengal’s radicalism have an impact on the nationalist leaders that Bengal would later produce?

Absolutely. The Bengal British Indian Society merged with the Landholders Society and became the British Indian Association (1851), which is recognised in our history books as the first Indian political party, and Peary Chand and Ramgopal were members of it too. Later, in 1885, the Indian National Congress came into existence in association with AO Hume, and it was almost the same as the Bengal British Indian Society, which had engaged the help of George Thompson in 1843. The two organisations were almost parallel, except for the nearly 50-year difference between them. It was only under the leadership of Gandhi that Congress matured into a different party.

To what extent did Mazzini’s Young Italy and Young Ireland shape the Young Bengal party?

Giuseppe Mazzini’s Young Italy and Young Ireland in Dublin were featured in the newspapers in Calcutta during the 1840s. It was only when the Calcutta press began to discuss Young Italy and Young Ireland that they realised something similar was happening in Calcutta, and they called it Young Bengal.

Story continues below this ad

You write that Young Bengal was “the crucible within which the Indian left first took place”. Could you expand on this idea?

Scholars such as Sumantra Banerjee and Chris Bayly have argued that Young Bengal’s ideas were similar to those of the Indian left, particularly in their rhetoric with regard to the oppression of the ryot (cultivator), the subaltern, and the “masses”. I have extensively cited their views on the oppressive land revenue system, the struggles of Bengal’s cultivators, and Peary Chand Mitra’s critique of the Permanent Settlement.

Bayly, in his book Recovering Liberties: Indian Thought in the Age of Liberalism and Empire, shows that their thinking was, in many ways, socialist in both their words and phrasing. And this, of course, was happening before Marx and Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto in 1848. So, this is sort of a prequel, if we can put it that way. That’s why I ask the question: Were they socialists in their thinking before the very word ‘socialism’ even came into existence?

Would you consider Young Bengal a failure?

By the end of the 19th century, ‘Young Bengal’ came to refer to anyone who was educated and progressive in their thinking. More importantly, in popular culture, they were often maligned as a group of radicals who studied Shakespeare, spoke in English, didn’t know Bengali well enough, and, above all, drank too much and achieved little. This slander became widely accepted as the general image of the group.

Story continues below this ad

In my book, I aim to dispel this image by highlighting the achievements of this group. What is rarely discussed is what they achieved because it is difficult to discuss, given the paucity of the archive in India and the lack of any actual legislative reform initiated by them. Yet Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee’s 1843 speech, where he condemned the corruption of the East India Company’s Courts of Judicature and Police, caused such a stir that the British were infuriated. Essentially, he was asserting that the British were far worse than the Mohammedan rulers who had come before them.

Young Bengal’s contributions have consistently been overlooked in the broader national struggle of Bengal.

How would Young Bengal resonate in today’s Bengal?

You’re asking for a speculative answer, and I wouldn’t like to speculate. However, I do think that it is the youth everywhere who see through the hypocrisy of the state most clearly, and they have the freedom to take up cudgels against that hypocrisy whenever and wherever they see it. So, I’m not even putting this in the context of Bengal; I’m putting it in the context of all of India and the world.

Now, you could argue that all these radicals or youths who have protested and raised their voices have achieved nothing. But, surely, something permeates into the Indian public sphere from their activities to those who take inspiration from their cause — the cause of fighting for the rights of Indians. Even if nothing immediate happens, the ideas and actions of these individuals make a difference to people everywhere who read about them.