When Professor Ananya Jahanara Kabir visited Pondicherry in 2019, her plan was to dig into the creole culture present in the city that once belonged to the erstwhile French colony. She set out to find traces of the influence that the French left behind, be it in terms of food, language, music, dance or just the general way of life. What came as a surprise however, was a perceptible and yet ignored presence of Vietnam in the memories and family histories of almost every Franco-Pondicherrian she met.

Ananya, who teaches English Literature at King’s College London, has been researching and theorising about creole communities in India, or rather cultures that are a product of unexpected encounters between the European and non-European worlds. In the midst of her research endeavour, Vietnam came out of the blue, and opened a whole new Pandora’s box.

Vietnam is like a “public secret” in Pondicherry, says Ananya. Almost every person seems to have a Vietnam connection and it is an extremely important part of the Franco-Pondicherrian understanding of who they are and their relationship to ‘Frenchness’. “It is so ubiquitous that it is actually quite startling how with this extreme imbrication of Vietnamese people in families, this memory is not much more public,” she says.

In research article titled, Creolising Archipelagic Intimacies: Remembering India and Vietnam via Pondicherry (spring 2025), Ananya has presented her findings from the investigations into the paradoxical Vietnamese presence in Pondicherrian lives: one which is both overbearingly present and yet almost invisible. In her conversation with indianexpress.com, she explained the complex colonial history that ties Vietnam to Pondicherry and the many residues it has left behind.

Can you give us a few examples of how Vietnam’s memory is preserved in Pondicherry?

Firstly, we have to think about Pondicherry itself in two ways. We have to think about Pondicherry as a material space, a geographic site, and a topography. It sits there. It’s a city. It’s got its monuments. It’s got its people, restaurants, churches, cemeteries, and more.

But we also have to think of Pondicherry as a diasporic space, both spatially located in Pondicherry itself, but also floating around in its diasporas. So we’re going to think about the Franco-Pondicherrians who are carrying parts of Pondicherry with them in France as well as other parts of the world.

The memory of Vietnam links these two kinds of Pondicherrian spaces together and creates a bigger frame. These memories, most importantly, are those of food. Because a lot of Franco-Pondicherrians regularly incorporate Vietnamese food in their cuisine, it will be cooked anywhere they live. It doesn’t have to be located within Pondicherry itself. For instance, there is the version of Vietnamese spring rolls which are called nem or chaiyo by Pondicherrians after cha gio, the terms used in South Vietnam. This favourite Franco-Pondicherrian snack is served at social gatherings worldwide.

Story continues below this ad

You will also find a strong presence of Vietnam in the cemeteries. If you go to the big cemeteries, the graveyards of Pondicherry people, you will find on the tombstones details of where people were born and where they died. And you will see Saigon or other places of Vietnam regularly inscribed on the tombstones. If you go to the churches, you will find statues and other donations from people who once lived in Saigon.

statue donated by the Pragassam family of Saigon to the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Pondicherry (Ananya Jahanara Kabir)

statue donated by the Pragassam family of Saigon to the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Pondicherry (Ananya Jahanara Kabir)

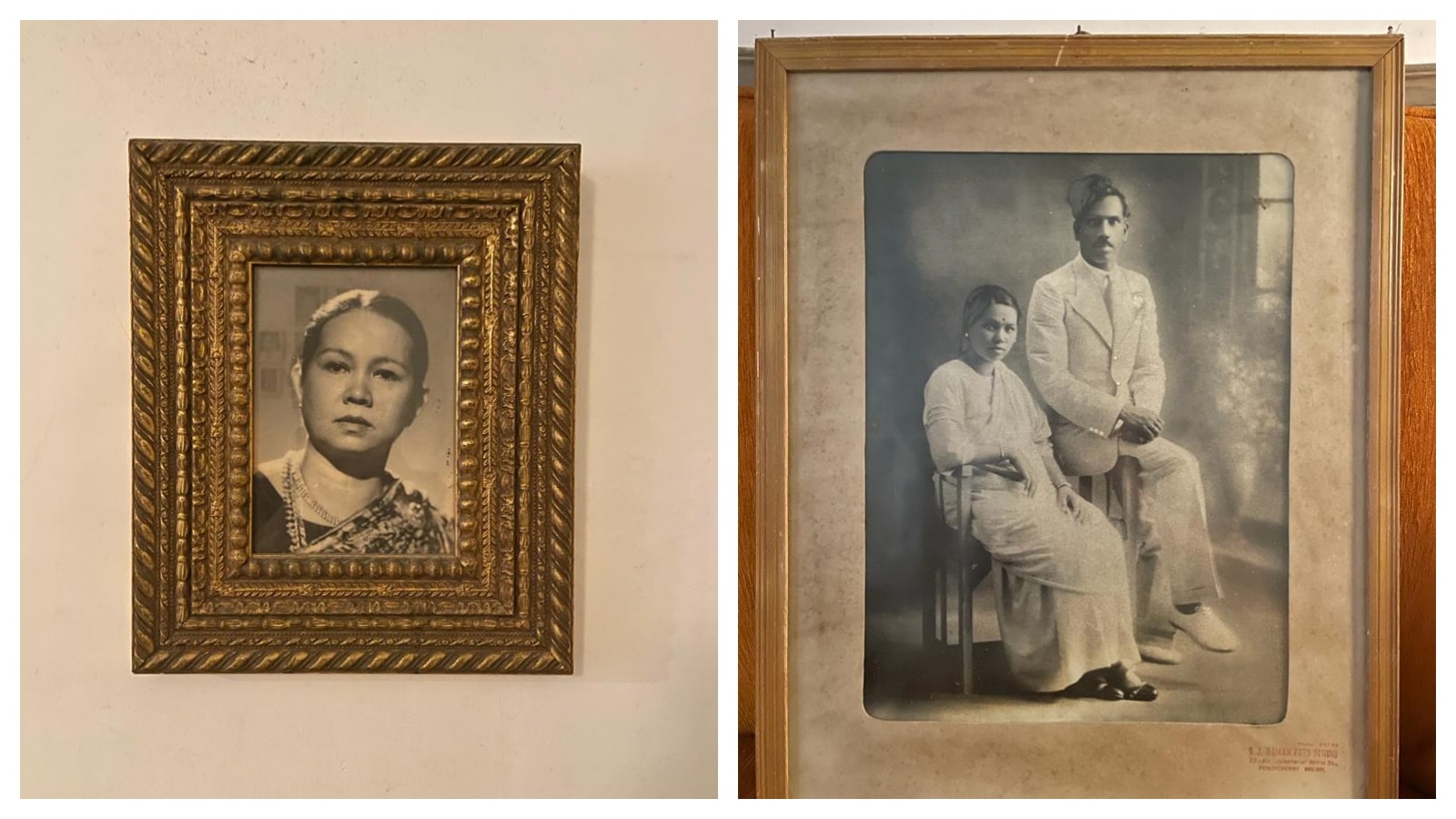

There are other subtle traces of Vietnam in Pondicherry’s memory — for instance, in the way people arrange their homes. I had come across this comment by a Vietnamese student who was in India for an exchange programme, wherein he said that whenever he entered the homes of Franco-Pondicherrian people he was reminded of the interiors of Vietnamese homes. There is a guest house in Pondicherry, Le Jardin Suffren. The reception area there is decorated with photographs of family members from Vietnam and paraphernalia like dragon motifs on the wall which are Southeast Asian.

The French colonial world included several other places apart from Vietnam, such as parts of Africa. Why is it that it is only Vietnam that made its way to Pondicherrian memory and not other parts of the empire?

To be honest, other parts of the French empire are also there. And this could be another project. In my article I have mentioned about people from Pondicherry travelling to places like Senegal and North Africa for work. That’s a whole other project and it’s worth working on. I chose to focus on the Vietnamese connection, because it’s the one that first floated up for me.

Story continues below this ad

But you may as well ask why out of all these layers of connections, the Vietnamese one is the one that floats up first. I think it’s perhaps because Pondicherry and Vietnam are two parts of the French empire that are within the Indian Ocean world.

Once the British took over India after the Anglo-French wars in the south, the French presence in India was gradually reduced to the enclaves of Pondicherry, Karikal, Yanam, Mahe, and Chandernagore. And they were not allowed to expand more. You have got to imagine that the French have lost real mobilising power in India, with a base but little else. So they were looking to see where they could go next and they found a fresh opening in Southeast Asia. They took over what they called “l’Indochine or ‘Indo-China’– basically it consisted of present-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

Photos from Le Jardin Suffren Guesthouse reception. (Ananya Jahanara Kabir)

Photos from Le Jardin Suffren Guesthouse reception. (Ananya Jahanara Kabir)

It’s even further away from France than India is, but they (the French) already have a base in India. They already have a few centuries of training of local people. So they had a corpus of Indian people who could speak French and were working in local administration. These were people who had renounced their Indianness, taken on French sounding names, become Catholic, and adopted the French language and education.

When the French took over Indochina, they had to send people there to administer the new colony. Instead of sending a shipload of people all the way from France, they just simply started creating a little circuit in Asia itself, between Pondicherry and Saigon and other parts, other locations of Indochina. Consequently, they started encouraging people from Pondicherry to fill the administrative gap in Vietnam. Historian Natasha Pairaudeau in her book Mobile Citizens: French Indians in Indochina, 1858-1955 writes exactly about this: Why did so many Pondicherrians get linked to the French Empire in Southeast Asia?

Story continues below this ad

A Franco-Pondicherrian agricultural scientist, the late Claude Maurius, whose memoir I have referred to, calls Indochina an “opening” because it represented, literally, a career opportunity for a whole bunch of people who had become French and were looking for new ways to express their Frenchness.

Was it just the bureaucrats who travelled from Pondicherry to Vietnam?

Once you had bureaucrats travelling along with their families, you would need a whole infrastructure to support them. So different kinds of people started travelling, sensing the opportunities. They included businessmen, jewellers, and bakers. In fact a whole caste of milkmen were taken along. Southeast Asians are known to be lactose intolerant and do not have a milk culture. So in order to meet with the requirements of the French and the Indians, people who deal with cows, and perhaps even the cows were sent across.

Therefore it was not just a small creamy layer of people who migrated, but four or five different groups of people. Natasha Pairaudeau in her work calls it a four-tiered diaspora that emerged. So there were merchants, bureaucrats, military men and finally the blue-collared workers, including those who were supplying milk.

Story continues below this ad

There was also the non-Franco-Pondicherrian lot who migrated, following those from Pondicherry, for example merchants and small-scale service providers looking for economic opportunities. In fact, I begin my article by reminding readers that the notorious Charles Sobhraj too had a Vietnamese mother and a Sindhi father.

You mention celebrated figures like singer Julie Quang, stunt coordinator Peter Hein, and the notorious serial killer Charles Sobhraj, who are all partly Vietnamese and Indian. And yet their mixed genealogy is almost invisible in public discussions. Why do you think that has happened?

We in India have a consciousness of ourselves as an ex-colony of the British. So stories and communities that are remnant of the British presence in India are easier to remember and understand. Thus, for instance, everybody in India would have an idea of who an Anglo-Indian person is. But they wouldn’t know much about the kinds of demographics and communities created through the French presence in India, including those with Vietnamese connections. Our memories collectively accept that textbook fact that for two hundred years we were a British colony.

Already within this framework the French colonial presence is pretty marginalised. And whatever we know of it is mainly because of heritage tourism which has become a big thing lately. What really shattered the links of memory between Vietnam and French India and later Pondicherry of the Indian republic, was the fact that all these spaces were involved in complex decolonisation processes of their own. On the Indian side, for instance, there was no need for an Indo-Vietnamese story because it just didn’t fit into the story about how we emerged out of anti-colonial resistance to British Rule.

Story continues below this ad

There is a big picture of British India, within that there are smaller pictures of Portuguese India and French India, and then within them there are mosaics of inner stories, such as the Franco-Tamlians in Vietnam or similarly the Goans who went to East Africa. The point is that nobody found it necessary to publicise the stories of these numerically smaller groups.

What is the memory of Pondicherry in Vietnam?

That would be the next step of this research project. We know that there are Tamil temples located there, for instance the Mariamman Temple at Saigon. We do know that in Vietnamese restaurants anywhere in the world, they always have a Vietnamese curry. The Vietnamese chicken curry, ‘ca ri ga’, is definitely a result of Indian influence in Vietnam. Even the curry powder that they have created is called ‘ca ri an do’ (Indian curry).

Of course, there is also an anti-Indian element in the local Vietnamese memory. It happened in so many other parts of the Indian Ocean world where Indians were present as important minorities because they were fitted into the colonial system, be it the Portuguese colonial system, the British, or the French. Pairaudeau examines in detail how cartoons and pamphlets presented Vietnamese ladies rejecting the Tamil milkman in favour of the new tinned condensed milk being supplied by companies like Nestlé. It is fascinating that the milkman who came all the way from Pondicherry became caught in the evolving relationship between European taste, industrialisation, and the Vietnamese people.

I would love to go to Vietnam and check for myself how these different memorial strands intertwine, but I would also love to follow the threads that connect Pondicherry to Senegal via Vietnam.

statue donated by the Pragassam family of Saigon to the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Pondicherry (Ananya Jahanara Kabir)

statue donated by the Pragassam family of Saigon to the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Pondicherry (Ananya Jahanara Kabir) Photos from Le Jardin Suffren Guesthouse reception. (Ananya Jahanara Kabir)

Photos from Le Jardin Suffren Guesthouse reception. (Ananya Jahanara Kabir)