The forgotten Belgian Jesuit priest who shaped India’s national science movement

Eugène Lafont arrived in Calcutta in 1865 as a Catholic missionary with a deep commitment to scientific education, and his vision aligned more closely with Indian aspirations for intellectual independence than with British colonial designs.

Eugène Lafont arrived in Calcutta in December 1865, not as a colonial administrator or a businessman seeking profit, but as a Catholic missionary with a deep commitment to scientific education. (Wikimedia Commons)

Eugène Lafont arrived in Calcutta in December 1865, not as a colonial administrator or a businessman seeking profit, but as a Catholic missionary with a deep commitment to scientific education. (Wikimedia Commons)Thomas Babington Macaulay’s notorious dismissal of Indian knowledge systems in 1835 — declaring that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia” — continues to dominate our understanding of colonial education. The prevailing narrative is simple: the British imposed their knowledge systems on India, uprooting indigenous traditions and creating a class of Indians who were “English in tastes, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” This story of colonial imposition versus Indian resistance has become so entrenched that we often miss the more complex reality of how modern science actually took root in 19th-century India.

What if I told you that one of the most crucial figures in establishing India’s “national science movement” was neither British nor Indian, but a Belgian Jesuit priest whose vision of scientific education aligned more closely with Indian aspirations for intellectual independence than with British colonial designs? Eugène Lafont arrived in Calcutta in December 1865, not as a colonial administrator or a businessman seeking profit, but as a Catholic missionary with a deep commitment to scientific education. Born in Mons, Belgium, in 1837, Lafont had trained in experimental physics at Namur before joining the St Xavier’s College faculty in Calcutta. What followed was a remarkable 43-year career that would reshape scientific education in colonial India in ways that challenge our conventional understanding of how modern knowledge systems developed.

When science met national aspirations

The India that Lafont encountered was far from the passive recipient of Western knowledge that colonial narratives suggest. As early as 1823, Raja Rammohan Roy had written to Lord Amherst, pleading for the government to employ “European gentlemen of talents and education to instruct the natives of India in Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, Anatomy, and other useful sciences.” Roy understood something that modern critics of colonial education often overlook: Indians were not merely being subjected to Western knowledge—they were actively demanding it, seeing science as the key to Europe’s political and technological supremacy. This demand for scientific education was not limited to Bengal. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan founded the Aligarh Scientific Society, while Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, speaking at Calcutta’s Albert Hall in 1882, declared that “science is the true sovereign” and directly linked European imperialism to the flourishing of sciences in Europe. These indigenous political actors operating within colonial contexts all argued for adopting modern science for societal progress—a position that Lafont would later echo and actively support.

Raja Ram Mohun Roy and Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (Wikimedia Commons)

Raja Ram Mohun Roy and Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (Wikimedia Commons)

But there was a crucial problem: the British colonial government showed little interest in promoting advanced scientific education among Indians. This neglect wasn’t accidental but reflected a deliberate policy rooted in imperial anxieties about creating an educated class that might challenge colonial authority. As one contemporary observer noted, higher learning would have “created more awareness among the natives and thereby fuelled discontent.” The University of Calcutta had dropped physical sciences from its BA curriculum in 1863, and when the Asiatic Society proposed in 1869 that science should be studied properly at the university level, the government refused, claiming “the time was not yet ripe.”

The discrimination went deeper than curriculum choices. As W S Atkinson, Director of Public Instruction in Bengal, dismissively remarked, the “degradation of national intellect among the Hindus” was “deep seated”. His successor, Alfred Croft, went further, claiming Indians were “temperamentally unfit to teach the exact method of modern science.” This wasn’t mere prejudice but strategic policy — the British had “carefully kept scientific departments as a close preserve for Europeans and Eurasians.” Even accomplished Indian scientists faced systematic discrimination: when J C Bose was appointed as the first Indian professor of physics at Presidency College in 1885, he received only one-third the salary of his European counterparts.

Ironically, this colonial neglect paralleled similar problems in early 19th-century Britain itself. As Charles Babbage had documented in his scathing 1830 critique, ‘Reflections on the Decline of Science in England’, British universities lagged behind their continental European counterparts in Prussia and the First Empire in France where there was state support for research universities. Despite the development of a rich scientific culture exemplified by figures such as John Dalton, Charles Lyell, James Joule and Michael Faraday, the British government provided little financial support for scientific research and did not employ scientists till the 1830s. Babbage’s campaign, alongside that of the British Association for the Advancement of Science founded in 1831, sought to professionalise science in Britain—but this modernisation was denied to India.

The Jesuit alternative

It was into this educational vacuum that Lafont stepped in with a radically different vision. From the very inception of the order, the Jesuits (Society of Jesus) had followed a scholastic path, establishing universities and being at the forefront of scientific activities since the 16th century: Christopher Clavius architected the Gregorian calendar reform of 1582; Christoph Scheiner systematically documented sunspots; Francesco Grimaldi discovered light diffraction; Giovanni Battista Riccioli measured gravitational acceleration and introduced the current system of lunar nomenclature; Roger Boscovich advanced knowledge on atomic theory; Angelo Secchi pioneered stellar spectroscopy.

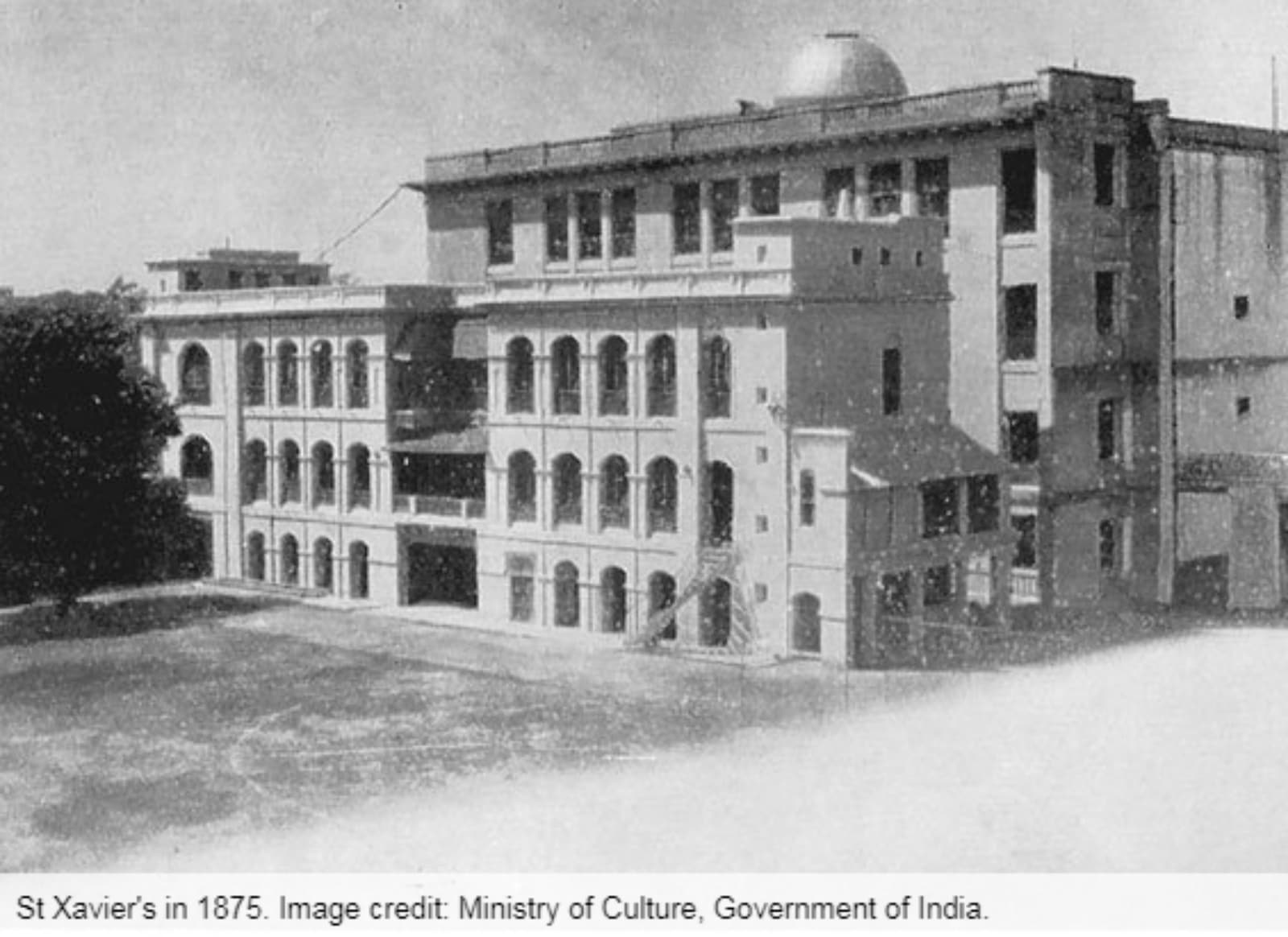

St Xavier’s College in Calcutta was established in 1860 as part of this tradition. Led by Henry Depelchin, who would later head the Zambezi missions, and Walter Steins, who became archbishop and Fellow of Calcutta University, eight Belgian Jesuits founded the institution at the old Sans Souci theatre site on Park Street. It was Depelchin who invited Lafont to replace Ignatius Carbonelle, another accomplished scientist who had taught at St Xavier’s from 1861 to 1867 before returning to Belgium to become the professor of mathematics and astronomy at Louvain and the founder of the Scientific Society of Brussels.

St Xaviers College Kolkata in 1875 (Ministry of Culture)

St Xaviers College Kolkata in 1875 (Ministry of Culture)

From its first prospectus in 1860, St Xavier’s College promised a “course of studies similar to the great colleges of Europe”, explicitly differentiating itself from British institutions. This distinction was crucial: while British universities were struggling to modernise their scientific curricula, continental European institutions — particularly the post-restoration Jesuit colleges — had successfully integrated modern scientific disciplines with humanistic education.

The post-1814 Jesuit educational strategy, codified in the reformed Ratio Studiorum of 1832, had embraced what they called “fundamental” rather than merely technical education. This approach, implemented across Jesuit institutions from Liverpool to Buenos Aires, insisted that scientific knowledge must be grounded in broader intellectual and moral formation. This pedagogical philosophy found remarkable resonance with Indian educational aspirations. Just as the medical professional and social reformer Dr Mahendralal Sarkar would later argue that science should serve moral and intellectual development rather than narrow vocational training, the Jesuits saw scientific education as a means of character formation and spiritual development.

For Lafont, trained in this tradition, science was never merely technical instruction but always connected to larger questions about divine order and human dignity. Lafont made ‘physical sciences’ compulsory for all students at St Xavier’s, even as the University of Calcutta was removing it from its curriculum. He established India’s first modern physics laboratory and meteorological observatory, equipped with cutting-edge instruments acquired through Jesuit networks across Europe. His barometric predictions saved countless lives during the devastating cyclone of November 1867, earning him widespread recognition and establishing his credibility as a serious scientist. Yet, Lafont’s impact went beyond individual achievements. He understood something that the British colonial administration missed: the difference between producing skilled workers and creating independent thinkers.

Lafont’s work also intersected with that of Pietro Angelo Secchi, the pioneering astrophysicist whose spectroscopic innovations had revolutionised astronomy in Rome. When Pietro Tacchini and Secchi arrived in India in 1874 to observe the transit of Venus across the Sun, it was Lafont who collaborated with them, establishing a spectroscopic laboratory at St Xavier’s College modelled on those in Palermo and Rome. Through this joint mission, Lafont transformed St Xavier’s into a node within international scientific networks, while his observations of solar protuberances and spectroscopic measurements contributed directly to the work of the Italian Society of Spectroscopists.

The great debate: technical training vs fundamental sciences

The founding of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Sciences (IACS) sparked a crucial debate that revealed the complex intellectual currents of the time. At a joint meeting in January 1876, the Indian League, led by nationalist journalist Shishir Kumar Ghosh, argued for technical and industrial training rather than abstract science. Rev K M Banerjea questioned the practical utility of pure science in a society where university graduates already struggled to find employment.

Sarkar, however, remained firm in his opposition to this vocational approach. “I want an institution,” he declared, “in which men may engage in long courses of original scientific research after they have passed through their pupillage.” It was here that Lafont provided crucial support, warning that “to teach the

applications of science without its principles is to put the cart before the horse.” This wasn’t merely a pedagogical dispute—it was a fight for intellectual dignity. Lafont recognised that technical training without fundamental understanding would perpetuate colonial dependency. When he supported Sarkar’s vision for the IACS in 1876, Lafont articulated a position that would seem remarkably prescient: “The other association wanted to transform the Hindus into a number of mechanics requiring forever European supervision, whereas Sarkar’s object was to emancipate in the long run his countrymen from this humiliating bondage.” His position echoed broader 19th-century debates across Europe about the relationship between classical education and scientific training, where evidence consistently showed that students with strong foundational education outperformed those with narrow technical training.

Finding God in all things: The theological dimension

What enabled a Catholic priest to become such a passionate advocate for Indian scientific independence? The answer lies in Jesuit theology and educational philosophy. Jesuits or the Society of Jesus had long embraced the maxim of “finding God in all things”, which allowed for a comfortable integration of scientific inquiry with religious faith. For Lafont, science was not a secular pursuit but a means of revealing the divine order in nature.

This theological framework aligned remarkably well with Sarkar’s own understanding of science. Sarkar, though a Hindu reformer, similarly viewed science as “a short name for positive knowledge acquired by the human intellect by coming into contact with the works of God”. Both men saw scientific practice not as materialistic reductionism but as a spiritual quest that could purify thought and cultivate moral character. This convergence wasn’t coincidental — it reflected broader global currents in 19th-century intellectual life where scientific authority was often mobilised to support religious and cultural revival rather than to displace it. The apparent conflict between science and religion that we often assume was more complex than traditionally portrayed.

A global movement

Lafont’s approach to science education was part of a worldwide Jesuit strategy that extended far beyond colonial India. In Liverpool, for instance, Fr Terence Donnelly was implementing remarkably similar reforms at St. Francis Xavier’s College, integrating modern scientific training with classical education to serve working-class Catholic students seeking upward mobility. Like Lafont, Donnelly resisted narrow vocationalism while embracing scientific innovation. This global perspective helps us understand why Lafont could simultaneously embrace cutting-edge spectroscopy and defend Catholic doctrine, or why his meteorological observatory could be connected to both Roman astronomers and Italian spectroscopists. Science in the 19th century was not simply “diffusing” from Europe to its colonies—it was being actively constructed through global networks that included missionary orders, indigenous intellectuals, and colonial institutions.

The legacy: From Bose to national science

The fruits of this collaboration between Lafont and Indian scientists like Sarkar became evident in the careers of their students. Jagadish Chandra Bose, who studied under Lafont at St Xavier’s and later conducted research at the IACS, became the first Indian physicist to lecture at the Royal Institution in London. His pioneering work in radio waves and plant physiology earned international recognition, proving that Indians could not only learn science but could contribute original discoveries to global knowledge. Yet even Bose faced the racial discrimination that Lafont had warned against. When appointed as the first Indian professor of physics at Presidency College in 1885, he was paid only one-third of what his European counterparts received. This discrimination vindicated the approach that Lafont and Sarkar had championed: Indians needed their own institutions where they could pursue science on their own terms.

Rethinking colonial education

The story of Eugène Lafont challenges several assumptions about colonial education. First, it shows that the demand for modern scientific knowledge came as much from Indians as it was imposed by colonisers. Second, it reveals that some of the most effective support for Indian intellectual independence came from unexpected quarters — not from British liberals but from Belgian Jesuits whose theological commitments aligned with Indian aspirations for dignity and autonomy.

Most importantly, Lafont’s career demonstrates that the development of modern science in India was not simply a story of Western knowledge overwhelming indigenous traditions. Instead, it was a complex process of negotiation, adaptation, and creative synthesis that involved multiple actors with different motivations but convergent goals. This does not mean that we should ignore the real violence and disruption that colonial education often entailed. But it does suggest that our understanding of this history needs to be more nuanced. When we reduce the story to a simple binary of colonial imposition versus indigenous resistance, we miss the creative ways in which Indian intellectuals and their allies — including figures like Lafont — worked to build institutions that could serve both scientific advancement and national dignity.

As India today grapples with questions about the relationship between traditional knowledge and modern science, between national pride and global engagement, the story of Eugène Lafont offers valuable insights. His career shows that it is possible to embrace modern scientific knowledge without abandoning cultural identity, to engage with global networks while maintaining institutional autonomy. Perhaps most importantly, Lafont’s collaboration with Sarkar demonstrates that the pursuit of scientific knowledge can be a deeply moral and spiritual enterprise, one that serves not just economic development but human flourishing in its broadest sense. In an era when science is often reduced to its technological applications, this vision of science as a tool for moral and intellectual development remains profoundly relevant. The Belgian Jesuit who spent his life in Calcutta may have been forgotten by popular history, but his legacy lives on in India’s scientific institutions and in the ideal of science as a means of human liberation rather than domination. That legacy deserves to be remembered — and its lessons applied to our contemporary challenges.

Rohan Basu is a doctoral scholar at the Department of Historical Studies, Central European University, Vienna.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05