How Christmas became a citywide ritual in Calcutta

From artillery salutes and ballroom dinners to Bow Barracks lights and Tangra feasts, a history of how Calcutta made Christmas its own.

New Market during Christmas, circa late nineteenth century; (Thacker and Spink)

New Market during Christmas, circa late nineteenth century; (Thacker and Spink)“In England, the celebration of Christmas Day has become stereotyped.” This was a lament with which began an article in The Saturday Review, titled Christmas in Calcutta, way back in the winter of 1894. It went on to argue that, as a result, “much may be done at Christmas time in the East which is impossible in the West,” for one could take “a typical Christmas Day in Calcutta, and spend it as it should be spent undeterred by the fetish of English Christmas traditions.” By then, Calcutta had indeed become one of the choicest hotspots for Christmas, or Burrah Din, celebrations in the East.

From artillery salutes to marigold festoons

Present-day Calcutta’s Christmas memories — of canopies of electric bulbs straining the winter sky over Bow Barracks and strings of light trembling above narrow lanes where porches spill paper crowns and kul kuls into the street — hark back to the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1875, when the festival began to be celebrated on a large scale in the British Indian capital and beyond.

However, Christmas celebrations in Calcutta were known to pass muster since at least 1780. The maverick Irish journalist, James Augustus Hickey, in his Hickey’s Bengal Gazette or the Calcutta General Advertiser of January 1781, commemorated the ceremonial character of Calcutta Christmases. On Christmas Day in 1780, the Governor-General Warren Hastings hosted a courthouse breakfast and presided over “the most sumptuous dinner”, attended by “many persons of Distinction”. Artillery salutes were fired from the grand battery at the ‘Loll Diggy’ (Lal Dighi), and the evening concluded with “a ball, cheer’d and enlivened by the Grand illumination and excellent band of Music.”

Then there is Mrs Eliza Fay’s letter from 1780, which also records the artillery salutes and banquets, besides home decorations, “large plantain trees” placed at principal entrances and the adorning of gates and pillars “with flowers fancifully disposed,” besides the surfeit of “fish and fruit” delivered by native servers.

The Scottish writer and painter, Constance Frederica Gordon-Cumming may have had Fay’s testimony in mind when she began her book In the Himalayas and on the Indian Plains (1884), with a vignette titled Christmas in Calcutta. There were, wrote Gordon-Cumming, “Christmas decorations here too; for the natives dearly love all tokens of feasting, and they place tall plantain leaves and bunches of fruit in the gateways, as symbols of plenty, and hang up wreaths of laurel and Indian jasmine, or strings of small lamps and of those great orange marigolds, which they offer at the shrines of all their gods.”

Christmas advertisements and Christmas cards

Long before Gordon-Cumming, however, colonial newspapers vividly chronicled Calcutta’s fireworks, gift fairs, processions, and banquets. The Bengal Hurkaru on the Christmas Eve of 1857, for instance, ran advertisements of Stilton cheese and turkey at David Wilson’s Great Eastern Hotel. The hotel’s ‘Hall of All Nations’, Calcutta’s chronicler Devasis Chattopadhyay notes, was stocked with elegant stores of Christmas goods, ranging from delicate meats to confectionery. It was not surprising for Governors-General and Viceroys to make Calcutta their winter retreat, where they enjoyed Christmas balls at Raj Bhavan, besides banquets and Polo matches.

A Statesman report from December 1882 described Calcutta at Christmas as “decorated and illuminated to live up the festive spirit” after Prince Albert’s visit, with the city’s decked-up luxury stores — Moore & Co, Messrs Mathewson’s and Wilson Mackenzie — playing host to “Christmas Pleasure Seekers” until dawn. On December 25, 1886, The Statesman reported the boom in Christmas business at Sir Stuart Hogg Market (or today’s New Market), which was already a key joint for shopping. Home to Jewish and Armenian confectioners, the city’s recipes of plum cakes, brandy-soaked plum puddings, and pastries would continue as culinary heirlooms among their descendants. The Anglo-Indian Club and exclusive European opened their doors on Christmas Day for dances and family gatherings, as Victorian Calcutta’s Christmas became a calendared metropolitan pageant.

“It is Christmas night,” recalled The Saturday Review, “and we have spent our feast-day as it should be spent in the Golden East.” By 1908, The Accountant would speak of institutionalised yuletide observances such as “the Botanical Gardens, at which the annual official Christmas Day picnic [was] held,” the tents on the Maidan, and shooting parties. As history enthusiast Somen Sengupta notes in a recent essay, “Christmas and New Year celebrations in Calcutta till the late-1950s was a cult and no less than a great cultural heritage of modern India.”

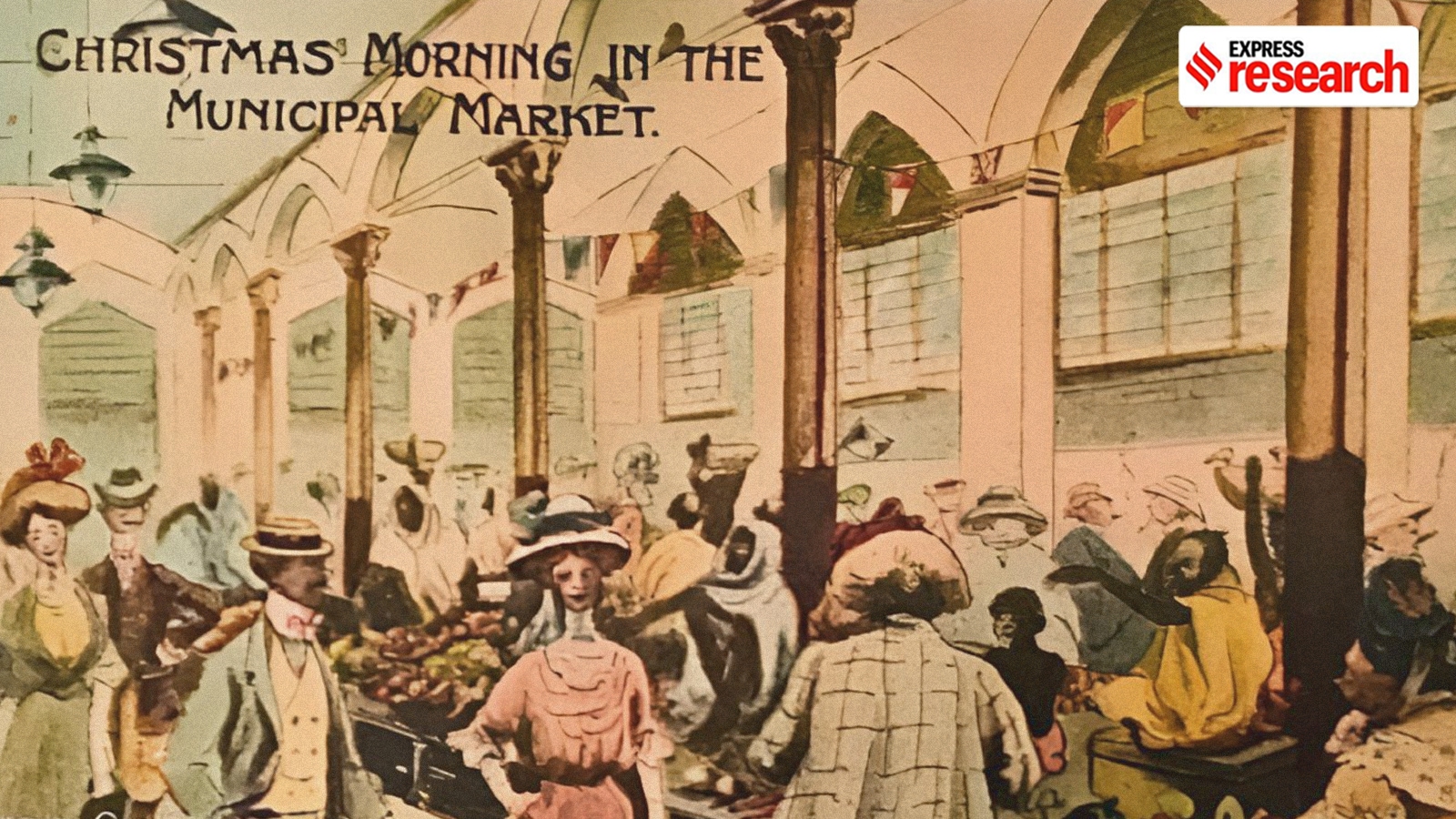

Indian Christmas Card by ‘Geo.D.’

Indian Christmas Card by ‘Geo.D.’

Historian Projit Bihari Mukharji adds that Calcutta’s Christmas evolved, understandably, “without much reference to traditional Christian themes and certainly little interest in snow-clad winters,” as the city created “its own distinctive flavor,” which included Christmas cards. Among these was a set printed between 1908 and 1912, illustrated by an anonymous artist who humorously signed his creations with ‘Geo. D.’ The cards were published by Thacker, Spink & Co., the eminent Calcutta-based publisher (1818-1933), also known for publishing the works of Rudyard Kipling, among others.

Clubs, cafes, and departmental stores

From the late nineteenth century, Calcutta’s luxury hotels and restaurants mounted elaborate Christmas and New Year buffets and entertainments. These included the Great Eastern Hotel, the Grand Hotel, Bristol, Continental, Firpo’s, Peliti, and Nahoum’s. Meanwhile, elite colonial clubs organised Christmas lunches, dinners and garden parties. Some of the prominent ones were the Bengal Club, the Calcutta Club, the Calcutta Cricket and Football Club (CCFC), and the Dalhousie Institute.

Established in 1907, the Calcutta Club’s Christmas celebrations were frequently attended by viceroys and other high officials, even after 1911, when Calcutta ceased to be the capital of British India. Lord Hardinge is known to have dined here on the Boxing Day of 1914, while Lady Hardinge and Lady Carmichael attended a garden party at the club. The Prince of Wales was present at a lunch at the Calcutta Club on December 28, 1921, attended by over 200 club members, on the same afternoon that he inaugurated the Victoria Memorial Hall to the public. On December 18, 1928, Viceroy Lord Irwin attended a garden party at the club and returned nine days later for a post-Christmas dinner.

Seasonal entertainment in Calcutta also included circus performances, wrestling exhibitions, theatre shows, magic shows, garden parties, river cruises, polo matches, horse races and cricket matches. Wilson Circus arrived in the city during the Christmas-New Year season of 1885, and, by 1925, the Royal Circus was running shows from December 12 onward, with nearly a hundred animals. Besides, elite polo and horse-racing events were held in December and January at the Calcutta Polo Club and the Royal Calcutta Turf Club.

Firpo’s, on Chowringhee Road, was known for gala festive lunches and dinners during Christmas week. Other major European-run department stores active during the season included Whiteway Laidlaw & Co., Hall & Anderson, Army & Navy Stores, and Moore & Co. They hosted staged annual Christmas bazaars and began sales campaigns as early as November.

Following the Prince of Wales’s visit, imported toys became a principal Christmas commodity, with Baker & Catliff, near Dalhousie, sending consignments to Calcutta. In the late 1880s, the Great Eastern Hotel was known for selling luxurious imported toys during Christmas and even beyond the winter months. As Sengupta notes, “Signor Peliti, the Italian bakery house that had the official contract to supply its produce to the Viceroy House, created giant cakes and recreated Delhi monuments replicas in cake.” In 1889, “before Christmas Eve, the same Peliti would create a 12-foot replica of the Eiffel Tower, which was “a guarantee of the elegance of the workmanship,”” he adds.

A Thacker and Spink advertisement in a British newspaper, during the Christmas season of 1894.

A Thacker and Spink advertisement in a British newspaper, during the Christmas season of 1894.After the First World War, gramophones and phonographs came to be in high demand as Christmas gifts. Dwarkin & Sons, the musical-instruments store on Lower Chitpur Road, advertised a New Edison gramophone priced at Rs 350 in 1925. That Christmas, the departmental store Hall & Anderson offered a 25 per cent discount on toys, crackers, cards and other Christmas offerings to meet stiff competition from rival stores. Meanwhile, Chowringhee-based Army & Navy Stores launched their Christmas campaign in early November through an attractive 100-page brochure with illustrated “details of crackers, hats, caps, novelties and toys,” according to Sengupta. Around this time, the Swiss confectionery Flury’s and Nahoum’s bakery had already been established.

New Market to Bow Barracks to Tangra

Compare this with the scenes that mark Calcutta’s Christmas today. At New Market, the pushcarts and shoppers thicken into a single human tide, as boxes of cakes from the Jewish Nahoum’s Bakery are passed hand to hand. And, in Tangra — the stronghold of the immigrant Chinese community in Calcutta — the steam from woks rises to precipitate a warm, oily perfume that draws late diners into neon restaurants.

Calcutta’s Christmas became a city-scale phenomenon in the late nineteenth century when festive practices migrated from parish halls to public streets. Gradually, it turned into a polyvalent festival of tremendous nostalgia and cultural value for not only Anglo-Indians, but also Changlindian (Chinese-Anglo-Indian fusion legatees), Muslims who became gleeful suppliers of bakarkhanis, and the Bengali public at large that still refers to the festival as ‘boro din’ (literally, ‘The Big Day’).

Far from a passive residue of colonial rule, Christmas in Calcutta is a centrifugal civic force. It stages neighbourhood solidarities, diasporic returns, and heritage politics, ultimately acting as a glue to preserve the city’s demographic and cultural integrity. Week-long street spectacles at Bow Barracks and the foodways of New Market and Tangra register Christmas as a public ritual.

Jayani Jeanne Bonnerjee’s doctoral research (2010) demonstrates how Anglo-Indians sustain the visible architecture of Calcutta’s Christmas. Schools, clubs, and charitable organisations stage concerts, lunches and performances in the weeks leading up to the holiday, some of them actively led by Loreto Convent Entally and the All India Anglo-Indian Association.

For Anglo-Indians, baking cakes and making kul kuls constitute key performative markers of their identity, according to Bonnerjee. The Changlindian soul of Calcutta’s Christmas makes it more cosmopolitan. Christmas in Calcutta is a critical site to examine how religious practice, education, and communal care intersect in a minority community. Approximately, four out of five members of the Anglo-Indian community in Calcutta are Roman Catholics, which helps explain the prominence of Mass and processions during the festival.

Bow Barracks, the old red-brick Anglo-Indian enclave in central Kolkata, is famous for its public Christmas celebrations (lights and decorations fill its lanes). Residents and visitors mingle under strings of stars and bells to listen to carols and enjoy food stalls. Located near Bowbazar, Bow Barracks has been known for its Christmas festivities since the last days of the First World War; it has enjoyed greater popularity with the Anjan Dutt-directed film, Bow Barracks Forever (2004).

The week-long Christmas programme hosted by Bow Barracks residents now runs from a concert on December 23 through a children’s party on Christmas Eve — when Santa Claus famously arrives in a rickshaw — and culminates in a senior citizens’ day on Boxing Day. In recent years, Santa Claus posters and figurines have depicted him wearing a dhoti and a kurta.

In Tangra, Hakka and other Chinese residents of Calcutta remember Christmas as a collective ritual of preparing chips, mashing up fish, and drying meats. To that assortment, add kathi rolls, phuchka, bhelpuri, and dalpuris, whereby citywide tastes cross religio-cultural lines.

Read through archival traces, Christmas in Calcutta is far more than a borrowed ceremony. The festival’s public life has a long history, wherein Bow Barracks, New Market, Nahoum’s, the Botanical Gardens, and St. Paul’s operate as sites of fluid memory. More than a borrowed pageant, it is an annual affirmation of plural belonging in the guise of a public practice that keeps the city’s complex micro-histories in circulation.

In the words of Gordon-Cumming, it is akin to “a gentle breeze blowing, and the two stout horses [that] whirl us along at a pleasant rate between the tall trees through Alipore … past the British Indian Docks,” before being ferried across the Ganga, “to the Botanical Gardens,” as we overlook “the green trees of the Gardens, behind the half ruinous buildings of the palace of the King of Oudh” — the vast realm of Calcutta’s ever-unfolding anecdotes.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05