Rethink on lateral entry to Waqf: Need for Modi govt to keep ally lines open

Responding to allies’ concerns and the Opposition’s demands indicates an inherent strength in Indian democracy. However, the recent rollbacks also underline the need for a mechanism for prior consultations in the NDA, and beyond it.

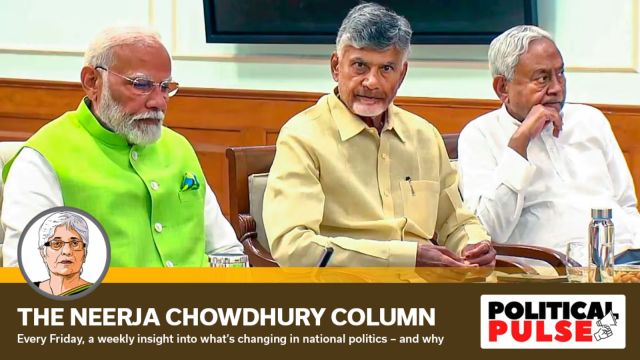

At present, the government is under pressure not just from its NDA allies that prop it up, or a combative Opposition out to corner it, but also from the RSS and the Hindu Right that feel the PM might be bending over backwards “to take everyone along”. (PTI)

At present, the government is under pressure not just from its NDA allies that prop it up, or a combative Opposition out to corner it, but also from the RSS and the Hindu Right that feel the PM might be bending over backwards “to take everyone along”. (PTI)The recent rollback of decisions, including the sudden withdrawal of an advertisement for the lateral entry of experts in the bureaucracy, has the potential to bring about a shift in the functioning of the Narendra Modi government.

The suddenness of the decision to get the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) to cancel the advertisement for 45 posts through lateral entry shows the initial decision was made without adequate consultations with allies. In the evening, Union Minister Arjun Ram Meghwal was making a case for it, citing how the Congress appointed Dr Manmohan Singh as Finance Secretary in 1976. The next day the advertisement was withdrawn.

While the TDP had no problem with lateral entry, this was not the case with the Chirag Paswan-led LJP (Ram Vilas) and the JD(U) that publicly opposed the move. They were worried about how the decision would affect their Dalit and Other Backward Class (OBC) base. The Congress had already slammed the move, calling it a backdoor method to scrap reservation for Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and OBCs in government services. Aware, that a perceived threat to reservation led to the BJP’s loss of a majority in the Lok Sabha polls, the BJP did not want to risk it again. The government beat a hasty retreat, reiterating its commitment to “social justice”. In other words, “lateral entry” with reservation.

In another surprise move, the government earlier this month withdrew the new draft of the controversial Broadcasting Bill on “regulating” print, electronic and digital media. It decided to come back with a “more comprehensive” Bill that would take into account the criticism of stakeholders. It also agreed, and did so readily enough, to send the Waqf (Amendment) Bill — another controversial legislation, it was seen as curbing the powers of the Waqf Boards and opposed by Muslims — to a Joint Committee of Parliament. This move, advocated by the TDP to enable more discussion on the Bill, would have been unthinkable in the BJP’s second term

At present, the government is under pressure not just from its NDA allies that prop it up, or a combative Opposition out to corner it, but also from the RSS and the Hindu Right that feel the PM might be bending over backwards “to take everyone along”. A BJP leader closely associated with the RSS said within months of Modi taking over as PM that the “real challenge in the future will come not from the Opposition but from the extreme Right”.

The BJP’s allies had also been left in a tough spot last month over the Uttar Pradesh Police’s order to eateries to display their names — it would have revealed their religious identity — along the Kanwar Yatra route. Had the Supreme Court not intervened to stay the implementation of the directive, the BJP might have been compelled to intervene in some way and risk inviting the charge of going against the interests of Hindus.

The BJP leadership has also defused an escalating crisis in UP BJP in the aftermath of the party’s poor performance in the Lok Sabha elections in the state, getting Deputy Chief Ministers Keshav Prasad Maurya and Brajesh Pathak to back down till the 10 Assembly bypolls in the state — the dates are yet to be notified — are over and providing CM Yogi Adityanath with some relief.

Bringing back Ram Madhav as election in-charge in Jammu and Kashmir shows that the RSS is asserting much more now. The government lifted the ban on government servants participating in RSS activities, apparently without the Sangh asking for it, to please it. Before that, the BJP had noted RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat’s two uncharacteristic statements indirectly criticising the PM.

Detailed deliberations between the RSS and BJP leaders are underway and one of the Sangh’s main concerns is the party organisation and who will head the BJP after J P Nadda. Nadda’s statement in the middle of the election season — that the BJP no longer requires handholding by the RSS — did not go down well with the Sangh leadership.

Since June 4, the Prime Minister has gone out of his way to give the impression that it is going to be business as usual, even though the BJP no longer commanded a majority on its own. The PM had his way in government formation, with the BJP’s allies not wrangling for heavy-duty portfolios. Modi also brought back Om Birla as the Lok Sabha Speaker, continued with Ajit Doval as the National Security Advisor (NSA), and retained P K Mishra as his principal secretary.

Making coalitions work

Some believe that having run the government with a convincing majority, first as the Gujarat CM and then as PM, Modi is not naturally given to consulting others before taking decisions. He likes to go in for “bhavya (grand)” decisions to bring big changes but often without calculating their fallout. But consultations are a sine qua non of coalition functioning. Vishwanath Pratap Singh, PM for 11 months, ran a coalition government that had the BJP and the Left. He used to meet BJP leaders every Tuesday evening and the Left leaders on another day to apprise them of the decisions he proposed to take. The only time he did not “consult” them, he once revealed, and only “informed” them was when he decided to implement the Mandal Commission report to give 27% reservation to OBCs in government jobs. It proved to be the undoing of his government.

P V Narasimha Rao who took the helm of a minority government led by Congres in 1991 was at his best dealing with allies, overt and covert. Regional satraps would see him regularly with their demands; his instructions were that wherever possible, their “work must be done”. Their names would not figure in the visitors’ manifest when they came to see him at his residence.

When Atal Bihari Vajpayee constituted his 24-party coalition government in 1998, “Mamata (Banerjee’s TMC)”, “Samata (George Fernandes’ Samata Party)”, and “Lalitha (Jayalalithaa’s AIDMK)” had put him in a tough spot by jostling for ministries. It led the Opposition to ask, “What has become of Vajpayee’s beatific smile?” But Vajpayee’s 1999-2004 term was known for his outreach to allies and Opposition parties alike.

Unlike 2014 and 2019, the BJP is again called to head a coalition government. The government’s recent rollbacks are dubbed by the Opposition as a sign of weakness, with the party’s Lok Sabha tally having gone down from 303 to 240. But should making the mandate work be seen as a sign of weakness?

Being responsive to the concerns of allies, the Opposition’s demands, and the pressure of public opinion indicates an inherent strength in our democracy. The rollbacks, however, also underline the need to put in place a mechanism for prior consultations in the NDA, and beyond it.

(Neerja Chowdhury, Contributing Editor, The Indian Express, has covered the last 11 Lok Sabha elections. She is the author of How Prime Ministers Decide)

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05