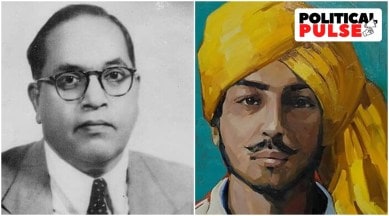

If B for Bhagat Singh, why A is for Ambedkar for AAP

From a close aide and old links, to a large following and big Dalit numbers, Babasaheb has a long history in Punjab

Never has Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar, architect of the Constitution, been invoked in Punjab as fervently and frequently as in the first week of the AAP government. One of the maiden decisions the Bhagwant Singh Mann-led government took was to install his picture along with that of Bhagat Singh in government offices, a practice that will now be followed in Delhi, which is also hosting a musical on Ambedkar.

🗞️ Subscribe Now: Get Express Premium to access the best Election reporting and analysis 🗞️

“We will run the state according to the ideals of Bhagat Singh and Babasaheb,” Mann promised at his swearing-in on March 16. Later, he announced statues of the two at the Punjab Vidhan Sabha in Chandigarh.

It’s a step that has won over Balwinder Jit, the Dalit sarpanch of Talhan village near Jalandhar, who admits he bucked the AAP wave to support the Akali-BSP candidate in the recent polls, only because he stood for “Babasaheb”. Singh, who breaks down while dwelling on the hardships Ambedkar had to endure during his life, says, “I’m glad he is finally getting his due in a state, from which he had high hopes. But the government must follow his ideals and not just restrict itself to iconography.”

Political observers see in it a strategy by AAP to counter the BJP’s hegemonic narrative. “In both Bhagat Singh and Babasaheb, they have two secular symbols with universal appeal. Together they symbolise the syncretic culture of Punjab,” says Dr Paramjit Singh Judge, a professor of political science at Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar.

Ambedkar as a symbol is central to the discourse of equality. He is not only iconic for Dalits, who form over 32% of Punjab’s population (the highest proportion in the country), but is also a symbol of individual equality enshrined in the Constitution.

In the recent Assembly elections, while the Congress hoped to consolidate SC votes by virtue of having installed Charanjit Singh Channi as the first Dalit CM of the state, the Akalis were banking on party president Sukhbir Singh Badal’s promise of a Dalit deputy CM and an Ambedkar university in the Doaba region, which has the largest Dalit numbers in the state. However, the community had voted like the rest of the state, and AAP had won 28 of the 34 reserved seats.

In Punjab, Ambedkar is a familiar presence, particularly in Doaba, where his portraits are commonplace. Both the Congress and Akali Dal pay their annual homage to him on his birth anniversary on April 14. After taking over as CM, Channi’s first step had been laying the foundation stone for an Ambedkar museum, spread over 250 acres, in Kapurthala. In 2020, a Post Matric Scholarship Scheme for SC students had been named by the Congress government after Ambedkar.

Prof Ronki Ram, an eminent Dalit scholar who occupies Shaheed Bhagat Singh chair in Panjab University, Chandigarh, says the two icons complement each other. If Ambedkar symbolises the Constitution and the values therein, “Bhagat Singh embodies the Preamble”, he says.

Prof Ronki Ram also talks about how Ambedkar’s connect with Punjab goes back to pre-Partition days. “After Maharashtra, it was from the Punjabi society that he got a large following and strength. His close aide Nanak Chand Rattu was from a village in Doaba.”

It was Rattu who discovered Ambedkar had died in his sleep. “Rattu said that the evening before his death, Babasaheb told him, ‘It’s with great effort that I have been able to bring this caravan till here, if they can’t push it further, don’t let it slide’,” says Prof Ronki Ram.

Mangu Ram Bugowal, founder of the Ad Dharam movement behind getting a distinct religious identity for SCs in Punjab, also revered Ambedkar, as did other community leaders such as Charan Das Nidhark and Kishan Das, a well-heeled leather merchant from Boota Mandi in Jalandhar.

Akalis, who claim to be the ones upholding the ideals of social justice espoused by Ambedkar, with schemes such as Shagun and atta-dal, were on good terms with the architect of the Constitution. The book ‘Fifty Years of Punjab Politics (1920-70)’, by Harcharan Singh Bajwa, member of the Akali Dal Working Committee from 1931 to 1960, claims that it was Ambedkar who had advised Akali leaders such as Giani Kartar Singh to seek a Punjabi suba instead of a Sikh state.

In the early years after Independence, the Republican Party of India, with its roots in the Scheduled Castes Federation led by Ambedkar, did well in Punjab.

In the present, Prof Emanual Nahar says the Congress victory in half-a-dozen seats dominated by Dalit Christians signals the political dividends that await AAP if it is successful in its Ambedkar appropriation. “Be it Gurdaspur, Dera Baba Nanak, or Qadian, the Congress won these seats only because the Dalit Christians voted en masse for the party. AAP has done well by honouring Babasaheb. He carved a unique identity for the Dalits, we can never forget him.’’

But in Mansa, the heart of Malwa, Bhagwant Singh Samon, the state president of the Mazdoor Mukti Morcha, is unmoved by these overtures. “Babasaheb was against buttparasti (idolatory). He used to scoff at this business of installing statues. AAP is merely using his name, they should instead try and follow his ideals.”