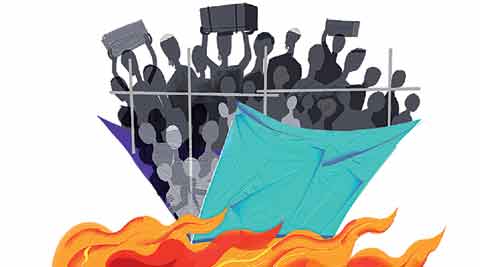

The protests in Assam against the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 point to the contentious nature of the proposed amendments. The bill was introduced in Parliament earlier this year, but opposition from the Congress and Left parties forced the government to refer it to a parliamentary panel, which had sought the views and suggestions of the public. The objections from the All Assam Students’ Union and various ethnic groups in Assam are premised on the fear that the amended bill could further increase migration into Assam. This fear is rooted in the politics that spawned the Assam agitation in the 1980s and led to the signing of the Assam Accord. While the fears of Assamese ethnic nationalists, even if exaggerated, arise from specific local concerns, the bill is most problematic, perhaps for another reason: It moves away from the vision of the founding fathers who refused to see the Indian state primarily as a Hindu nation.

At the core of the bill is the proposal to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955 so that members of minority communities – Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain and Parsi – from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh could acquire Indian citizenship faster than at present. Now it takes 12 years of residency for any non-citizen to acquire Indian citizenship by naturalisation. The amendment proposes that a person from any of the aforesaid countries could acquire citizenship (by naturalisation) within seven years even if the applicant does not have the required documents. However, and here lies the problem, this provision is not extended to Muslims from these countries. The move to relax the conditions for acquiring Indian citizenship is unexceptionable, but surely the enabling criterion cannot be based on the applicant’s religion.